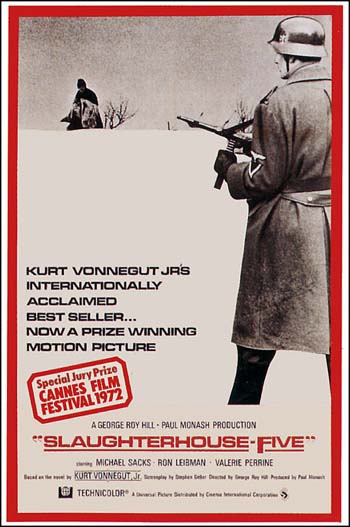

Following up yesterday’s Memorial Day post, I have come across articles making the case that two classic works by World War II veterans were shaped by the authors’ problems with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This psychological angle has heightened my admiration for Slaughterhouse 5 and Catcher in the Rye because I have a better sense how Kurt Vonnegut and J. D. Salinger used their writing to work through the horrors of the war.

Vonnegut, of course, was a prisoner of war in the open city of Dresden when the British bombed it to avenge the London blitzkrieg. The book explicitly talks about how Vonnegut spent years trying to put the horrors of the bombing in a novel, but William Deresiewicz’s article in The Nation (tip to Andrew Sullivan) argues that Slaughterhouse 5 is actually about the PTSD flashbacks that Vonnegut suffered as the result of his traumatic captivity::

It’s not about time travel and flying saucers, it’s about PTSD. Vonnegut never explicitly negates the former possibility, but the evidence for the latter is overwhelming once you start to notice it. Billy Pilgrim, whose wartime experience closely parallels Vonnegut’s own, does not announce his abduction to the planet Tralfamadore, where he is displayed in a zoo and mated with the Earthling porn star Montana Wildhack—with the strong suggestion that he doesn’t imagine it, either—until after the plane crash that replays, in several respects, his wartime trauma. Despite the way we flesh them out in our minds into the semblance of a real story—as Vonnegut surely knew we would—the scenes on Tralfamadore add up to no more than a handful of discontinuous fragments: a moment in the flying saucer, a moment in the zoo and a few moments with Montana Wildhack, amounting altogether to scarcely ten pages. The whole scenario turns out to derive from a Kilgore Trout novel that Billy had read years before (as well as sharing plot points with The Sirens of Titan). And the compensatory nature of the wisdom Billy claims to learn up there is all too clear. The Tralfamadorians see in four dimensions, the fourth one being time. “The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past.”

Billy’s time travel is equally imaginary—or to use a word that Vonnegut promotes to the title page this time, schizophrenic. As he bounces willy-nilly around his life (“unstuck in time,” as the narrative’s opening puts it)—an optometrist at one moment, a hunted conscript in the aftermath of the Battle of the Bulge at the next; now in Dresden, now a little boy; walking out of his honeymoon suite to find himself in a prison camp—what he’s really doing is remembering and, more often, dreaming. “Billy fell asleep under his blanket” (this is in a mental ward at a VA hospital in 1948). “When he woke up again, he was tied to the bed in the hospital back in prison.” Urged by his bride to speak about his wartime secrets, the “things you don’t want to talk about,” Billy says: “It would sound like a dream.”

The novel isn’t about flying saucers, and it isn’t finally about Dresden, either. The raid gave Vonnegut the peg on which to hang the book and goaded him with a sense of occasion—of having stumbled into precious literary material—but as he had lamented to himself for years, he hadn’t actually seen it, safe in the deep, sealed basement of the slaughterhouse. Only once he realized that his true subject was his own long ordeal as a prisoner of war—fleeing, starving, packed for days in a cattle car, put to slave labor, almost killed by German guards and American planes, watching his fellow prisoners die all around him—was he able at last, I believe, to write the book. Billy’s time travel begins when that begins: when he’s lost and alone in the woods and the snow, apparently abandoned by his comrades, ill-clad, ill-trained, ill-equipped, a plaything of forces beyond his comprehension.

The novel is framed by Vonnegut’s account of trying to write about Dresden—of trying to remember Dresden. But a different kind of memory became the novel’s very fabric. “He tried to remember how old he was, couldn’t.” This is Billy the optometrist. “He tried to remember what year it was. He couldn’t remember that, either.” For the traumatized soldier, the war is always present, and the present is always the war. He is unstuck in time in the sense that he is stuck in time. His life is not linear, but radiates instead from a single event like the spokes of a wheel. Everything feels like a dream: a very bad dream. The novel is framed the way it is because Vonnegut, too, was traveling in time. He needed to make himself a part of the story because he already was a part of the story.

But Slaughterhouse 5 at least is set in World War II. Kenneth Slawenski argues in a Vanity Fair article that Catcher in the Rye was also shaped by the author’s combat trauma, even though the war is never mentioned in the book:

For Salinger himself, writing The Catcher in the Rye was an act of liberation. The bruising of Salinger’s faith by the terrible events of war is reflected in Holden’s loss of faith, caused by the death of his brother Allie. The memory of fallen friends haunted Salinger for years, just as Holden was haunted by the ghost of his brother. The struggle of Holden Caulfield echoes the spiritual journey of the author. In both author and character, the tragedy is the same: a shattered innocence. Holden’s reaction is shown through his scorn of adult phoniness and compromise. Salinger’s reaction was personal despondency, through which his eyes were opened to the darker forces of human nature.

Both eventually came to terms with the burdens they carried, and their epiphanies were the same. Holden comes to realize he can enter adulthood without becoming false and sacrificing his values; Salinger came to accept that knowledge of evil did not ensure damnation. The experience of war gave a voice to Salinger, and therefore to Holden Caulfield. He is no longer speaking only for himself—he is reaching out to all of us.

I find it inspiring that authors suffering from an illness as shattering as PTSD can transmute the experience into works of art. I also find it fascinating that one of those works would speak directly to the alienation of young people in the 1960s and early 1970s as they faced the prospect of being drafted and that the other would speak to teenagers all over the world (60 million copies sold worldwide and counting) who are going through the trauma of adolescence. The ability of stories to speak to our condition and help us work through our issues never ceases to amaze.

Added note: My father, a World War II veteran, sent me the following note about Slaughterhouse Five after reading this post. He said he found himself so horrified by the scene where Paul Lazzaro boasts about killing a dog by feeding it a steak with razor-sharp pieces of a spring that the novel fell in his estimation: “Not that it wasn’t accurate because it probably was–but I was so horrified in WWII to witness many examples of the ‘torture of innocents’ that that one instance of horrible revenge in the otherwise admirable book made me sick. Especially as I had seen examples of GIs torturing elderly German citizens after the War was over.”