Wednesday

In Monday’s essay I suggested Kafka could help Americans negotiate the apparent bad news they are getting from Attorney General William Barr’s summation of the Mueller Report. While (according to Barr) the report did not exonerate the Trump campaign for covering up its relations with Russia when it interfered in the 2016 election, it did clear it of criminal complicity. Those Trump critics who dreamed Mueller would hold Trump accountable were heartbroken.

Joe Scarborough, host of MSNBC’s Morning Joe, observed that he hadn’t seen Democrats so disconsolate since Trump unexpectedly won the presidency, While Trump’s partial exoneration didn’t cause me a week of sleepless nights as his election did, I certainly experienced Barr’s letter as a blow. Kafka helps me understand why.

Some background is useful. Many of us who are privileged and idealistic have a stake in the system, in part because it has benefited us. We believe in Constitutional checks and balances, the Bill of Rights, an independent judiciary. Even when we witness breakdowns, we are convinced that things will right themselves eventually. Our prosperous lives lead us to be complacent.

If one has been a victim of the system, however—I’m thinking mainly of Native Americans, African Americans, and other people of color—one’s perspective is often less rosy. To be sure, such people might still believe in America’s promise, but many have too much familiarity with a rigged system to have illusions.

Interestingly, this makes them better able to handle those moments when the world goes haywire. Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim noted this phenomenon at work after spending a year (1938-39) in a German concentration camp. The people who fell apart, he said, were those who had been comfortably well-off and didn’t know why they were there. Those who had been persecuted had a frame of reference that sustained them.

My friend Rachel Kranz had a passage about this in her novel Mastery (unfortunately she died before it was completed). The occasion is a New York dinner party:

“You know who survived in the concentration camps longest?” Molly asks, and a shiver goes through the whole room as everybody very carefully avoids looking at Joshua [a child of survivors]. Does she really not know? is what everyone is obviously thinking. But Molly barrels on.

“Communists,” she says triumphantly. “Because they saw every little thing they did as an act of resistance. And that gave them the courage to survive.”

Simon sighs—once again, he can’t help himself. “And Jehovah’s Witnesses,” he points out. “And Orthodox Jews. Anyone who believed they were on some kind of mission to save the world felt that way.”

“No,” says Molly. “Everyone who believed that every little act had meaning. Like God was watching. Or History,” and somehow we all hear the capital “h.” “That belief is what kept them going.”

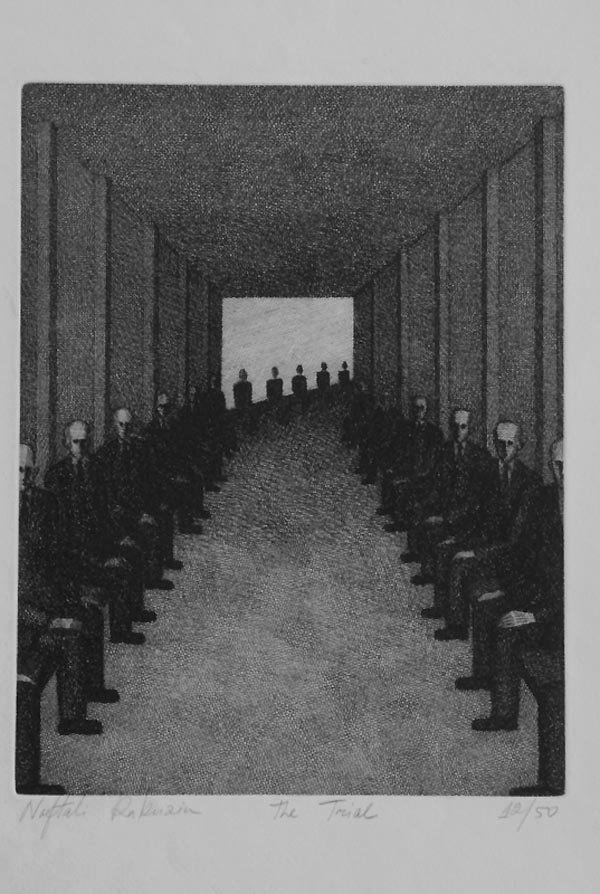

K, the protagonist of Kafka’s Trial, is not a communist or a Jehovah’s Witness or an Orthodox Jew. (If he’s like Kafka, he’s a cosmopolitan, middle class Jew.) Out of nowhere, he is accused of a crime but never discovers for what. At one point in his search for clarification, a priest tells him an enigmatic parable that speaks to his situation.

It’s about a man who journeys from the country to a law court, presumably seeking some kind of justice. When he finds his way barred by a doorkeeper, he spends years waiting for entry. While the doorkeeper isn’t unfriendly, he is also unyielding:

The man from the country had not expected difficulties like this, the law was supposed to be accessible for anyone at any time, he thinks, but now he looks more closely at the doorkeeper in his fur coat, sees his big hooked nose, his long thin tartar-beard, and he decides it’s better to wait until he has permission to enter. The doorkeeper gives him a stool and lets him sit down to one side of the gate. He sits there for days and years. He tries to be allowed in time and again and tires the doorkeeper with his requests. The doorkeeper often questions him, asking about where he’s from and many other things, but these are disinterested questions such as great men ask, and he always ends up by telling him he still can’t let him in. The man had come well equipped for his journey, and uses everything, however valuable, to bribe the doorkeeper. He accepts everything, but as he does so he says, ‘I’ll only accept this so that you don’t think there’s anything you’ve failed to do’. Over many years, the man watches the doorkeeper almost without a break.

The man eventually becomes becomes old and sick, and the parable concludes in characteristic Kafka fashion:

“Finally his eyes grow dim, and he no longer knows whether it’s really getting darker or just his eyes that are deceiving him. But he seems now to see an inextinguishable light begin to shine from the darkness behind the door. He doesn’t have long to live now. Just before he dies, he brings together all his experience from all this time into one question which he has still never put to the doorkeeper. He beckons to him, as he’s no longer able to raise his stiff body. The doorkeeper has to bend over deeply as the difference in their sizes has changed very much to the disadvantage of the man. ‘What is it you want to know now?’ asks the doorkeeper, ‘You’re insatiable.’ ‘Everyone wants access to the law,’ says the man, ‘how come, over all these years, no- one but me has asked to be let in?’ The doorkeeper can see the man’s come to his end, his hearing has faded, and so, so that he can be heard, he shouts to him: ‘Nobody else could have got in this way, as this entrance was meant only for you. Now I’ll go and close it.'”

There’s no definitive reading of the parable. K and the priest debate several interpretations, and scholarly essays and dissertations have been written about it. Reading it in light of our current moment, however, I see the man as someone who believes in the system with a faith that he never abandons. That faith, however, operates as his own personal prison. He thinks the system is supposed to work in his favor but it never does. Only at the end of his life does he start asking questions that, had he asked them earlier, might have freed him from waiting. At that point, the door closes and he dies.

To date, all we know about the Mueller Report is what the Attorney General’s “press release” reveals. Barr promises something more complete in “weeks, not months,” but that report could be carefully edited. Will we get through one doorkeeper only to encounter another?

The gateway to the law is open as it always is, and the doorkeeper has stepped to one side, so the man bends over to try and see in. When the doorkeeper notices this he laughs and says, “If you’re tempted give it a try, try and go in even though I say you can’t. Careful though: I’m powerful. And I’m only the lowliest of all the doormen. But there’s a doorkeeper for each of the rooms and each of them is more powerful than the last. It’s more than I can stand just to look at the third one.”

Even if we see the full Mueller Report in all its glory, do we think it will deliver a final and convincing verdict? After all, Mueller has encountered his own doorkeepers, including witnesses who have clammed up at the prospect of a presidential pardon and a president who has refused to answer his questions.

People like me find ourselves suddenly questioning the American system because see a man flout democratic norms like no previous president. We thought that our electoral process would take him down and then that Congress would play an oversight role. When the GOP-run Congress failed to play watchdog, we put our faith in a special counsel. With this hope apparently thwarted, some are turning to other investigations that have been opened into Trump.

Previously unimaginable scenarios suddenly seem possible. What if Trump, already a minority president, is once again reelected thanks to foreign assistance and his own skullduggery? What if he is defeated but refuses to step down, as his former fixer Michael Cohen suggests might happen. Will we still sit patiently by the door, waiting for the system to to self-correct? Will we die waiting?

Kafka reminds us that, as some point, we must start asking foundational questions.