Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Friday

The presence of anti-Semitic campus leftists who lionize Hamas terrorism while arguing for the elimination of the state of Israel is taking me back to my college days, when both the Civil Rights movement and the anti-war movement had their share of extremists. I remember hearing Martin Luther King (this in Charleston in 1967) when he responded to Black militants with, “It’s not burn, baby, burn but build, baby, build.” Meanwhile, peaceful Vietnam War protesters were derided by the Underground Weathermen, who said they/we weren’t going far enough.

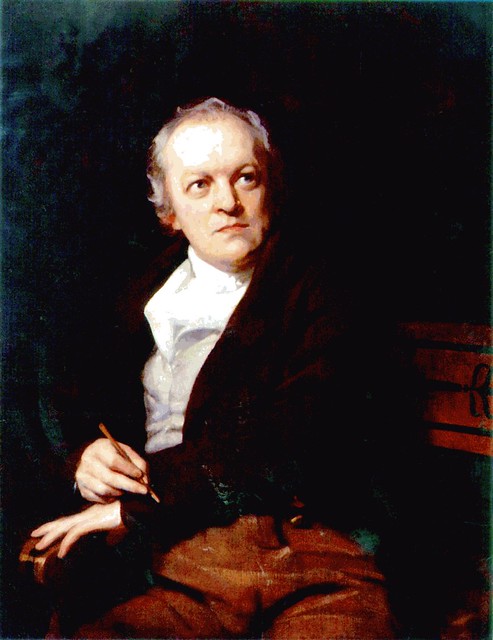

While leftwing militancy today doesn’t pose the same dangers as rightwing militancy—occupying college campuses isn’t the same existential threat to the country as seizing the Capitol, and we haven’t seen leftists implicated in mass shootings—it still must be called out. Gaza supporters directing hate speech against Jews are no less disturbing than Islamophobes and Palestinian haters. Few poets have better credentials for such calling out than William Blake, who does so in his poem “The Grey Monk.” More on this in a moment.

First, a little on my own activist background. Speaking as one who was arrested during a peaceful protest following the Kent State shootings—we blocked the Hennepin County draft induction center in Minneapolis for two hours before police came and, with no resistance from us, took us to Hennepin County jail—I remember thinking of Trotskyist, Maoist, anarchist, and Black militants as mostly bullshitters. But they also revealed a disturbing authoritarian streak that mirrored the very forces that they were opposing.

In fact, that authoritarian streak would reveal itself in time. Just as a number of 1950s Troskyists would become hardened reactionaries in the 1960s, so it was not surprising to see figures like the New Left’s David Horowitz and Black Power’s Eldridge Cleaver embrace the intolerant right.

Unlike them, Blake maintained a balanced perspective.

Blake’s activist credentials are beyond question. Here’s a summation:

In 1780, Blake was among the crowd that stormed Newgate Prison and freed its inmates. (The assault was the culmination of the Gordon Riots, a set of events that started as an anti-Catholic protest and turned into a fundamental challenge to inequality, the king, and an unrepresentative parliament.) In 1791, he wrote a long poem about the French Revolution. It was too admiring for even his left-wing publisher, John Johnson, to present to the public. Two years later, he wrote and illustrated a book, America a Prophecy, celebrated the American Revolution and endorsed abolitionism. In another book he published that year, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, he examined, through metaphor and personification, what is today called “rape culture” and argued for women’s sexual and creative emancipation. In 1804, Blake was charged with sedition for punching a soldier and allegedly saying, “Damn the king.”(It’s unclear if he actually uttered the phrase, though he wrote, in private literary notations, “Every Body hates a King.”

Blake’s activism put him at far greater risk than American activists in the 1960s and early 1970s. For his so-called sedition, which occurred when fears of a French invasion were high, he could have been executed. Only a good lawyer was able to get him off.

“Grey Monk” begins with a cry of suffering, one which those Palestinian and Israeli parents of dead children can relate to:

I die I die the Mother said

My Children die for lack of Bread

What more has the merciless Tyrant said

The Monk sat down on the Stony Bed

The Grey Monk, an avatar for Blake himself, is a Christ-like witness to the suffering:

The blood red ran from the Grey Monks side

His hands & feet were wounded wide

His Body bent his arms & knees

Like to the roots of ancient trees

His eye was dry no tear could flow

A hollow groan first spoke his woe

He trembled & shudderd upon the Bed

At length with a feeble cry he said

While God, Blake writes, has commanded him to write to protest injustice, he acknowledges that his writing could elicit an opposite response than that which he desires. That’s the reason for his feeble, almost defeated, cry. He embraces love but is seeing his protest lead to hatred and violence, which are “the Bane of all that on Earth I lovd”:

When God commanded this hand to write

In the studious hours of deep midnight

He told me the writing I wrote should prove

The Bane of all that on Earth I lovd

Before explaining how, he returns to his theme of suffering and of his own willingness to endure torture to say truth to power:

My Brother starvd between two Walls

His Childrens Cry my Soul appalls

I mockd at the wrack & griding chain

My bent body mocks their torturing pain

Then, however, comes the response he fears. He probably is thinking foremost of the Reign of Terror that followed the French Revolution:

Thy Father drew his sword in the North

With his thousands strong he marched forth

Thy Brother has armd himself in Steel

To avenge the wrongs thy Children feel

And now the caution. Only love, not force, can “free the World from fear.” His declaration that “a tear in an Intellectual Thing”—an apparently contradictory statement since tears are of the heart rather than of the head—is (I think) a response to how people regarded the French Revolution as an outgrowth of the Age of Reason. While a revolutionary himself, Blake believes that the heart rather than the head must take the lead:

But vain the Sword & vain the Bow

They never can work Wars overthrow

The Hermits Prayer & the Widows tear

Alone can free the World from fear

For a Tear is an Intellectual Thing

And a Sigh is the Sword of an Angel King

And the bitter groan of the Martyrs woe

Is an Arrow from the Almighties Bow

And then Blake’s grand finale, which is a warning that every activist should memorize and hold close:

The hand of Vengeance found the Bed

To which the Purple Tyrant fled

The iron hand crushd the Tyrants head

And became a Tyrant in his stead”

From long history we know this truth only too well. Since the founding of Israel, the Middle East has been witnessing non-stop tit-for-tat vengeance. In practically every instance, tyranny has proved the victor.

Yes, we must speak out against suffering, Blake’s Grey Monk tells us. But we must do so with humility and care, knowing that even well-intentioned protesters can have their own inner tyrant.