Monday

Yesterday I mentioned Lucille Clifton’s poem “blessing the boats (at st. mary’s).” As I explain below, it was written while Lucille was a colleague at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. I find it a miraculous poem:

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

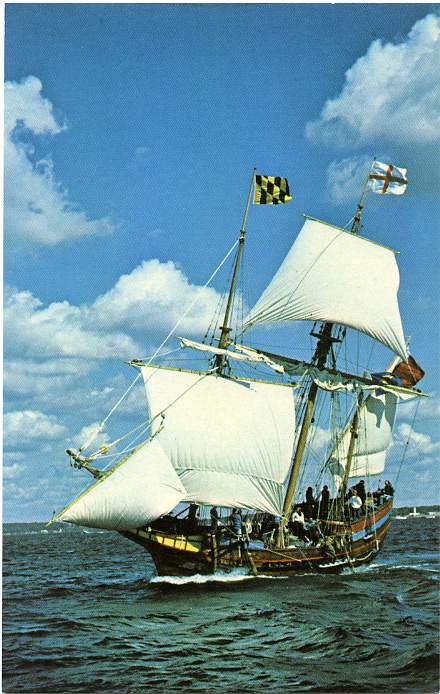

The title refers to the Blessing of the Fleet that occurs every October at St. Clement’s Island, Maryland. It commemorates the blessing of the Arc and the Dove in England, which set off with the first English settlers in Maryland in 1633. They landed at St. Clement’s five months later. A modern replica of the Dove is pictured above.

At St. Mary’s College, however, we take the poem to refer to us. After all, we are a campus defined by our waterfront on the St. Mary’s River. There are almost always boats on the river and we have long had one of the top sailing programs in the country. This poem is inscribed on the wall of our campus center so that students will see it on their way to the dining hall.

In this way, the poem serves to put a frame around the St. Mary’s educational experience. For it is not, of course, only about boats. It is about people venturing into the unknown and about other people, those who love them, letting them go. The adventurers may be fearful and they may be passing beyond the lip of our understanding, but they can rest assured that they will have the wind of love—of their parents, teachers, and friends—supporting them. Those who are waving from the shore ask only for a momentary kiss and then accept that our children and students will be focused on the horizon and on the “water/ water waving forever.”

The image of waving, incidentally, reminds me of the penultimate paragraph in the James Baldwin short story “Sonny’s Blues” where Sonny’s fellow jazz musicians are trying to entice him back into music after a prison stint for heroine. Sonny’s brother sees how hesitant Sonny is about playing again but also notes how the band leader is assuring him that all will be well:

He wanted Sonny to leave the shoreline and strike out for the deep water. He was Sonny’s witness that deep water and drowning were not the same thing–he had been there, and he knew.

In Lucille’s poem, I love the image of the wind, a divine spirit that propels and that will be with the sailors always. I also enjoy Lucille’s word play in “love your back.” The “your” sounds like Black dialectic for “you,” pointing to confidence that love will remain even when the one who loves is absent. But it also functions as a possessive pronoun—you can go forth confident because we have your back.

In the end, it doesn’t matter what the “this” and the “that” are. What counts is our wide-eyed openness to the

Monday

Yesterday I mentioned Lucille Clifton’s poem “blessing the boats (at st. mary’s).” As I explain below, it was written while Lucille was a colleague at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. I find it a miraculous poem:

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

may you kiss

the wind then turn from it

certain that it will

love your back may you

open your eyes to water

water waving forever

and may you in your innocence

sail through this to that

The title refers to the Blessing of the Fleet that occurs every October at St. Clement’s Island, Maryland. It commemorates the blessing of the Arc and the Dove in England, which set off with the first English settlers in Maryland in 1633. They landed at St. Clement’s five months later. A modern replica of the Dove is pictured above.

At St. Mary’s College, however, we take the poem to refer to us. After all, we are a campus defined by our waterfront on the St. Mary’s River. There are almost always boats on the water and we have long had one of the top sailing programs in the country. This poem is inscribed on the wall of our campus center so that students will see it on their way to the dining hall.

In this way, the poem serves to put a frame around the St. Mary’s educational experience. For it is not, of course, only about boats. It is about people venturing into the unknown and about other people, those who love them, letting them go. The adventurers may be fearful and they may be passing beyond the lip of our understanding, but they can rest assured that they will have the wind of love—of their parents, teachers, and friends—supporting them. Those who are waving from the shore ask only for a momentary kiss and then accept that our children and students will be focused on the horizon and on the “water/ water waving forever.”

The image of waving, incidentally, reminds me of the penultimate paragraph in the James Baldwin short story “Sonny’s Blues” where Sonny’s fellow jazz musicians are trying to entice him back into music after a prison stint for heroine. Sonny’s brother sees how hesitant Sonny is about playing again but also notes how the band leader in assuring him that all will be well:

He wanted Sonny to leave the shoreline and strike out for the deep water. He was Sonny’s witness that deep water and drowning were not the same thing–he had been there, and he knew.

In Lucille’s poem, I love the image of the wind, a divine spirit that propels and that will be with the sailors always. I also enjoy Lucille’s word play in “love your back.” The “your” sounds like Black dialect for “you,” pointing to confidence that love will remain even when the one who loves is absent. But it also functions as a possessive pronoun—you can go forth confident because we have your back.

In the end, it doesn’t matter where we sail from or to. What matters is our wide-eyed openness to the journey.

The poem has been read several times at St. Mary’s commencements. Indeed, our ceremony is set up in a way that conforms with the idea in the poem. When our students first come to St. Mary’s, we greet them in a convocation where they have their backs to the St. Mary’s River. Then the chairs are turned around during the graduation ceremonies, and the students can see the river beyond the speakers’ platform.

In the end, it doesn’t matter where we sail from or to, this or that. What matters is our wide-eyed openness to the journey.

The poem has been read several times at St. Mary’s commencements. Indeed, our ceremony is set up in a way that conforms with the idea in the poem. When our students first come to St. Mary’s, we greet them in a convocation where they have their backs to the St. Mary’s River. Then the chairs are turned around during the graduation ceremonies, and the students can see the river beyond the speakers’ platform.

Every time I reread the poem, I think of the many students I have taught, sailing out into unknown waters. While most I never see or hear about again, I love them all, just the same.