Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

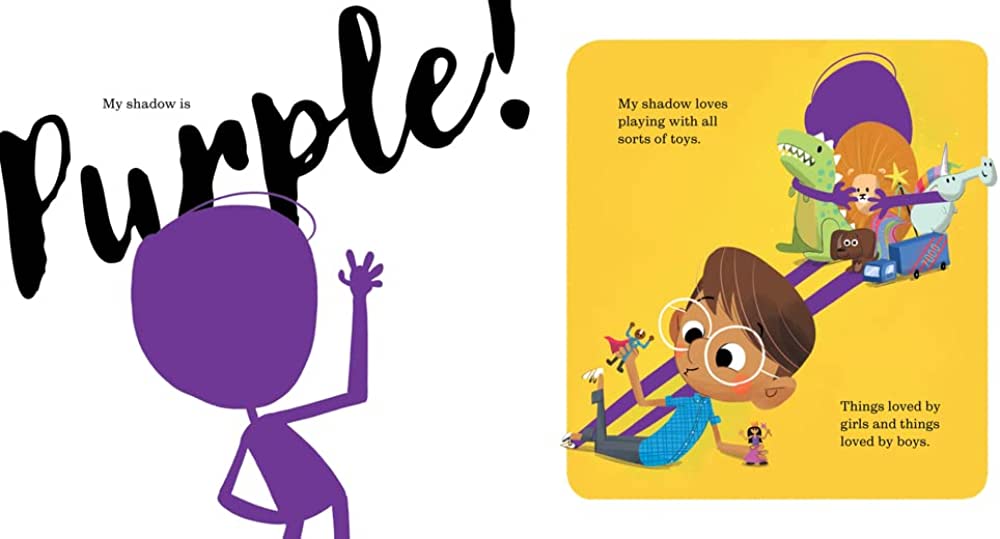

Just a week before the Supreme Court ruled that it’s okay for Christians to discriminate against LGBTQ+ people, news broke that a fifth grade Georgia teacher is being fired for reading to her class Stuart Scott’s My Shadow Is Purple. Her infraction is teaching “divisive concepts.” The book is about a boy who likes both traditionally boy things (trains) and girl things (glitter).

As Washington Post commentators Greg Sargent and Paul Waldman observe, the book’s conclusion is that “sometimes blue and pink don’t really capture kids’ full interests and personalities — and that everyone is unique and should just be themselves.” The offended parent complained, ““I would consider anything in the genre of ‘LGBT’ and ‘Queer’ divisive.”

The “divisive” in Georgia’s law is apparently whatever an affronted parent considers to be divisive. Sargent and Waldman point out that the vagueness of the law is part of the point, allowing rightwing parents to object to—well—pretty much anything. Don’t look to the law itself for examples since those it provides all have to do with race, not gender.

“Divisive,” according to these examples, includes “the idea that the United States is ‘fundamentally racist and that people should feel ‘guilt’ or bear ‘responsibility’ for past actions on account of their race.” But despite the failure in the law to mention anything regarding gender, the school decided to adopt that parent’s complaint as policy and to sacrifice Katherine Rinderle.

Also sacrificed are those students who would benefit from the book’s message. Speaking for myself, I desperately needed this assurance when I was that age. As a bookish child who didn’t like fighting or football (a religion in Tennessee), I remember thinking that a mistake had been made somewhere. Maybe I was a girl in a boy’s body.

I’ve written in the past how I was drawn to books in which there are versions of the purple shadow drama. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy was particularly important to me, featuring as it did a boy with long hair (crewcuts were the fashion in the 1950s) whose mother dressed him in velvet and lace collars—and yet who was (as I was) a very fast runner. I thus related to the following scene:

Mr. Havisham found himself leaning out of the window of his coupe with a curious feeling of interest. He really never remembered having seen anything quite like the way in which his lordship’s lordly little red legs flew up behind his knickerbockers and tore over the ground as he shot out in the race at the signal word. He shut his small hands and set his face against the wind; his bright hair streamed out behind.

“Hooray, Ced Errol!” all the boys shouted, dancing and shrieking with excitement. “Hooray, Billy Williams! Hooray, Ceddie! Hooray, Billy! Hooray! ‘Ray! ‘Ray!”

“I really believe he is going to win,” said Mr. Havisham. The way in which the red legs flew and flashed up and down, the shrieks of the boys, the wild efforts of Billy Williams, whose brown legs were not to be despised, as they followed closely in the rear of the red legs, made him feel some excitement. “I really—I really can’t help hoping he will win!” he said, with an apologetic sort of cough. At that moment, the wildest yell of all went up from the dancing, hopping boys. With one last frantic leap the future Earl of Dorincourt had reached the lamppost at the end of the block and touched it, just two seconds before Billy Williams flung himself at it, panting.

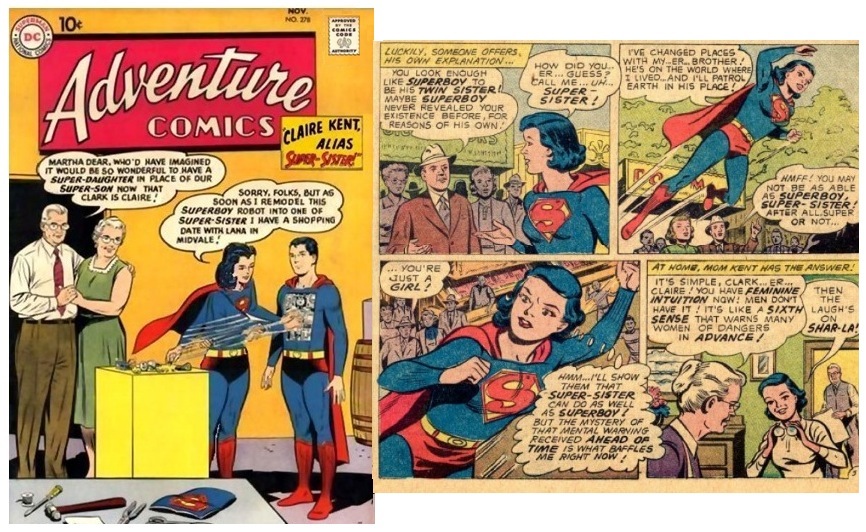

I also was riveted by the figure of Tip in The Land of Oz (the second of the Oz books), who is in actuality Ozma of Oz, having been transformed into a boy by a wicked witch. And then there was the episode in one of the Superboy comic books where Kent finds himself transformed into a girl. It turns out to have been a dream, but in that dream his mother renames him Clare Kent and he adds “female intuition” to his superpowers.

The work that had the most profound impact on me was Twelfth Night. When I was in 7th grade, I developed a case of mono, probably caused by stress over the civil rights battles our town was undergoing at the time. My father brought home Shakespeare on records from the English Department’s collection, and I listened to Viola’s gender crossing adventures over and over. I most related to the scene where Viola is confronted by an amusement-seeking Sir Toby Belch, who wants her to duel the cowardly Sir Andrew Aguecheek.

I knew exactly how Viola—female inside, male outside—felt when pressured to fight. This particular scene captured my painful reality while a follow-up scene provided me with a fantasy wish fulfillment: although the first fight is interrupted, in the follow-up challenge Sir Toby mistakenly targets Viola’s twin brother, who proceeds to beat the crap out of both him and Sir Andrew. This unexpected reversal is a version of the fantasy that appeared in the ads at the end of our comic books, where a wimp lifts barbells (which you could order) and thrashes the bully who has kicked sand in his face.

Now, I was drawn to all these stories, not because I wanted to be a girl, but because the 1950s stereotype of boys didn’t match up with my internal reality. What I needed were narratives that honored gender complexity. Shakespeare, who understood human beings as well as anyone ever has, provided me with one.

So will Georgia now fire teachers for teaching 12th Night? All it takes, apparently, is for one parent to call it divisive.

Georgia teachers would definitely face trouble for recommending a book that my wife found in England and gave to our 11-year-old grandson. David Williams’s The Boy in a Dress is about a 12-year-old boy who, missing a mother who has left, tries out her dresses and reads copies of her Vogue magazines. As one thing leads to another, Dennis befriends a sympathetic girl, who helps him in his attempt to pass himself off as a girl at school.

He is caught and expelled but, because he is the soccer team’s star player, his teammates don dresses in a show of solidarity and with his help come back from six goals down to beat their rival. That this other team is notorious for playing rough and dirty—in other words, they’re driven by toxic masculinity—helps make the book’s point that children need to explore alternative narratives.

It so happens that my grandson, who loves to dress up, has sometimes experimented with wearing a skirt to school. He assures me that his pronouns are still he/his and I assure him that I will love him regardless of pronoun. But he may well be, as he currently thinks, cisgender. After all, he’s like his father, who as a boy wore his hair long and who once, for Halloween, passed himself off as a creditable girl in one of Julia’s dresses. He also played Bianca in a cross-dressing version of Taming of the Shrew while studying theatre in London.

Years ago, a University of Hawaii biologist left our college Gender Studies colloquium with a quote I have never forgotten. Milt Diamond noted that not everyone is limited to either the XX or the XY chromosome combination: apparently there are some trisomies (XXX, XXY, XYY), even some tetrasomies (XXXY, XXXX), and yet still other possibilities. And if one adds to the mix those XXes who loves other XXes and those XYs who love other XYs (and I’m only getting started), one can nod vigorously to the observation Diamond shared with us: Nature loves variety, human society hates it.

If you want to see real perversity, look at those people quashing—sometimes through shame, sometimes through worse—their children’s identity explorations. Some of the actual groomers we hear about, including some GOP politicians, were denied healthy avenues of expression as children. What they repressed returned as something monstrous.

If we want our children to grow into mature, well-balanced adults, we need teachers like Katherine Rinderle.