Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

My dear friend Rebecca Adams sent me a fascinating article on Gen Z members who are pushing back against “phone-based childhood.” In “The Youth Rebellion is Growing,” Zach Rausch and Jon Haidt profile seven leaders who are actively working to reduce the serious harms associated with cellphones.

One of these leaders, Ben Spagloss, could be a poster child for better living through literature. Thanks to a mentor he met in high school, Spagloss went from non-reader to voracious reader. Now, as an adult, he uses TikTok to persuade people to get off their phones. He also wants us all to pressure Congress to pass the Kids Online Safety Act, which tech companies are fighting with a $60 million a year lobbying effort.

As Spagloss describes his outreach to his 190,000 followers,

I will try to get people interested in books, or post at night to help people to power off and sleep. I will also try to teach different behavioral change skills to help people navigate some of the internal barriers that can make change so hard.”

It’s ironic that Spagloss uses his phone to persuade others to abandon theirs, but how else would he do it? As he puts it, “My generation’s world is online, so I thought I’d try to reach people there.”

Spagloss reports that books received no respect in his high school, where

“reading a book” was a joke. The laugh-out-loud kind of funny. The reality was SparkNotes, CliffNotes, your friend’s notes, or whatever you found online to get the assignment done. The real school we went to every day was the Internet. The social media platforms had a perfect attendance rate, but what they were giving to the kids, nobody knew at the time.

What changed him was an after-school tutor who became a father figure. The man saw through Spagloss’s tough and uncaring act, teaching him “that loving others and aspiring to change the world was a much better philosophy.”

Imitating his mentor, Spagloss turned to books, reading 50 his first year and “a couple hundred” the year after. Reading changed the way he saw his phone.

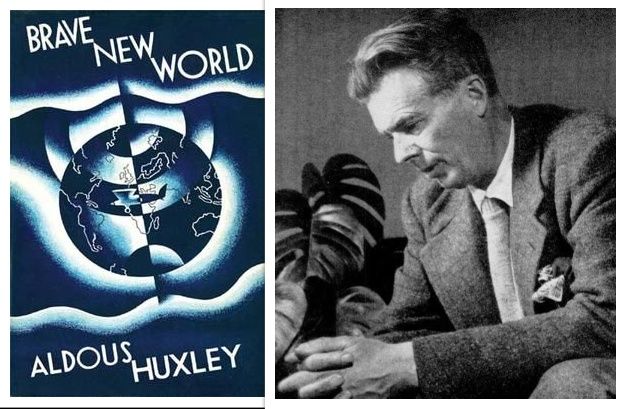

It was in part this new perspective that drew him to dystopian or speculative fiction. While bookish adolescents are generally attracted to this genre—after all, they’re beginning to think beyond their family and peer units to explore the broader world—Spagloss was most fascinated by a work that is sometimes overshadowed by 1984, The Road, The Stand, Handmaid’s Tale, The Giver, Fahrenheit 451, Parable of the Sower, Station Eleven, The Hunger Games, and the Oryx and Crake trilogy. Looking at his concerns, however, one can see why Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World would strike a chord.

As Spagloss points out, in Huxley’s work “the typical antagonist of the tyrannical government isn’t present. Instead, the protagonist is the antagonist. The people oppress themselves.” Because the authorities encourage consumerism and endless entertainment and freely allow both sex and drug use, the citizenry doesn’t aspire to anything more. As Bernard Marx, a discontented character, observes, people used to read and think, whereas now

the old men work, the old men copulate, the old men have no time, no leisure from pleasure, not a moment to sit down and think or if ever by some unlucky chance such a crevice of time should yawn in the solid substance of their distractions, there is always soma, delicious soma, half a gramme for a half-holiday, a gramme for a week-end, two grammes for a trip to the gorgeous East, three for a dark eternity on the moon; returning whence they find themselves on the other side of the crevice, safe on the solid ground of daily labor and distraction, scampering from feely [movie] to feely, from girl to pneumatic girl, from Electromagnetic Golf course to…”

Spagloss sees Brave New World as even more relevant now than it was in the early 1930s, when it first appeared. He observes,

It pointed to a world where the books don’t burn, but the libraries are left unchecked. Where information is not deprived from people, but given in incomprehensible abundance. Where the culture is not controlled but instead trivial, comedic, sexual, or roasted. In this world, people are not controlled by inflicting pain, but pleasure. It was a world without pain, poetry, truth, or meaning. I saw pleasure, when Huxley and later [Neil] Postman, pointed from their graves to my phone with their stories.

American culture critic Postman, whose 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, saw Brave New World rather than 1984 as our future in his book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. I wonder what he’d say now, what with the rise of Donald Trump in this country and of authoritarian regimes around the world. Orwell seems only too relevant, especially the dictum, “The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.”

As I think about this further, however, one can combine both dystopias: what we are currently experiencing is a reality television host performing Big Brother wannabe for the entertainment of his fans. Trump has become the drug of choice for a swath of the American public, some of whom saw invading the U.S. Capitol as freedom fighter cosplay. (Meanwhile some of Trump’s enablers in Congress have described them as “tourists” and “hostages.”)

In Brave New World, meanwhile, John the Savage, seeking to escape a world in which constant drugs and entertainment numb the senses, engages in self-flagellation with a ceremonial whip—but that just becomes a new form of entertainment for the jaded multitudes. What are the feelies and soma to spectator sadism?

“The whip,” answered a hundred voices confusedly. “Do the whipping stunt. Let’s see the whipping stunt.”

Then, in unison and on a slow, heavy rhythm, “We-want-the whip,” shouted a group at the end of the line. “We-want-the whip.”

Others at once took up the cry, and the phrase was repeated, parrot- fashion, again and again, with an ever-growing volume of sound, until, by the seventh or eighth reiteration, no other word was being spoken. “We-want- the whip.”

They were all crying together; and, intoxicated by the noise, the unanimity, the sense of rhythmical atonement, they might, it seemed, have gone on for hours almost indefinitely.

When Lenina, a sexually charged woman who has been trying to seduce John, rushes out to him, he turns the whip first on her and then back on himself. The crowd has gotten what they came for:

With a whoop of delighted excitement the line broke; there was a convergent stampede towards that magnetic center of attraction. Pain was a fascinating horror.

Their subsequent behavior is akin to all those MAGA bullies who, inspired by Trump, confront people in supermarkets, shopping malls, parks, and other venues. It’s as though they have been given permission to lash out, and they turn on each other and on Lenina, who is on the ground:

Drawn by the fascination of the horror of pain and, from within, impelled by that habit of cooperation, that desire for unanimity and atonement, which their conditioning had so ineradicably implanted in them, they began to mime the frenzy of his gestures, striking at one another as the Savage struck at his own rebellious flesh, or at that plump incarnation of turpitude writhing in the heather at his feet.

I can’t help but see the storming of the Capitol in the scene.

Tom Nichols, a former Republican who writes for the Atlantic, has been calling America “an unserious country” for close to a decade now, seeing us “in the grip both of trivial silliness and dead-serious psychosis.” When people are more interested in being entertained than in governing, we have a Huxley society. Unfortunately, Huxley is only a step away from Orwell since there are authoritarians-in-waiting who are more than eager, with a Trump victory, to install a Christo-fascist state. And if that happens, the reality television show that is American politics will turn deadly serious. Actual pain will ensue.

Can literature stop this? Well, if it alerts Gen Z leaders like Ben Spagloss to these dangers—and if he can persuade his fellows to put down their phones and pay attention to what’s happening—then at least there will be pushback.