Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Sunday

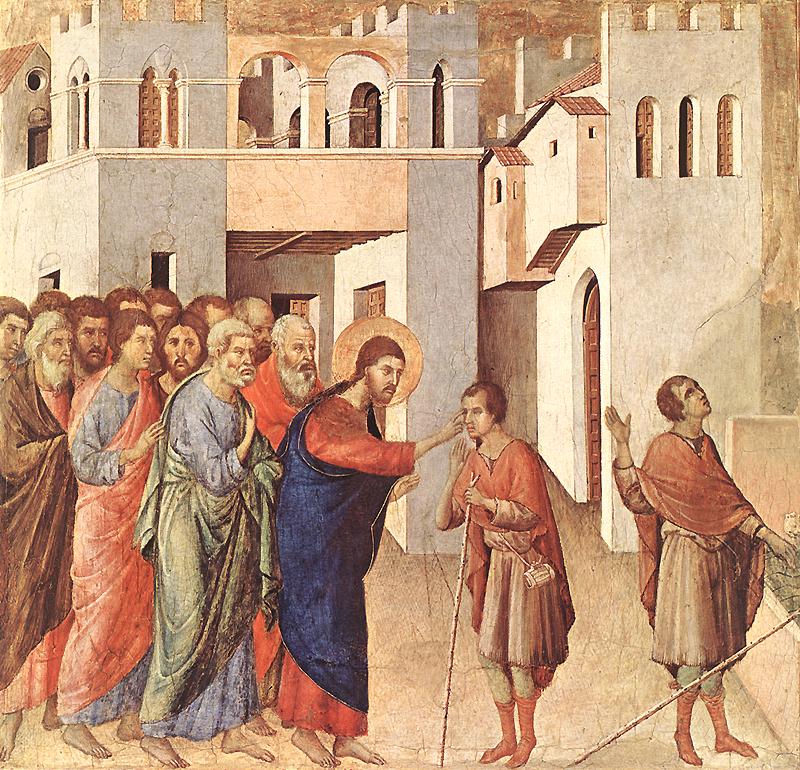

Each time the Gospel reading in our church features an account of Jesus curing someone, I turn to Lory Hess’s essential book When Fragments Make a Whole: A Personal Journey through Healing Stories in the Bible. Hess responds to each of these stories with a poem, a spiritual interpretation, and an account of how the story has addressed her own version of the illness. With the story of blind Bartimaeus, Hess shows how we don’t have to be blind for Jesus’s healing miracle to be applicable.

The story occurs in Mark 10:46-52:

Jesus and his disciples came to Jericho. As he and his disciples and a large crowd were leaving Jericho, Bartimaeus son of Timaeus, a blind beggar, was sitting by the roadside. When he heard that it was Jesus of Nazareth, he began to shout out and say, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” Many sternly ordered him to be quiet, but he cried out even more loudly, “Son of David, have mercy on me!” Jesus stood still and said, “Call him here.” And they called the blind man, saying to him, “Take heart; get up, he is calling you.” So throwing off his cloak, he sprang up and came to Jesus. Then Jesus said to him, “What do you want me to do for you?” The blind man said to him, “My teacher, let me see again.” Jesus said to him, “Go; your faith has made you well.” Immediately he regained his sight and followed him on the way.

Hess notes that blindness can be spiritual as well as physical:

The greatest danger for the human today…is that we will lose our sense of life, that we will no longer be able to choose life over death because we cannot tell the difference between them, or we actually prefer the state of death to life. It is a crisis of perception and discernment that requires us to assess the way in which we see.

Hess goes on to say that there are two kinds of seeing,

one that is suited to the sense world and one to the spiritual world, and neither is better than the other. The sickness, or the ‘guilt’, comes in when we confuse the two, when we cannot pass from one to the other when necessary or apply them in appropriate ways. True sickness lies in not knowing one is sick, and true blindness in not knowing one is blind.

Through healing Bartimaeus, Hess contends, Jesus was also conveying a lesson to his disciples. When Jesus’s death robs them of his “sense-perceptible presence,” she says, it is uncertain whether they will be able to manage their vision of Christ. Healing Bartimaeus, then, is “a final instruction for them to look upward.”

She then turns to her own sickness, which involved migraine headaches and a serious gallbladder problem. Blind to the messages her body was sending her, she says, it took her a long while to muster up the courage to listen to the “hidden wisdom deep inside me.” Only these was she able to “navigate the next steps toward finding out what it was that my true self really wanted.”

Hess’s poem, told from the perspective of Bartimaeus, is about opening ourselves to this inner light:

Blind Bartimaeus

By Lory Hess

It’s a heavy fate,

a child born blind.

Everyone wonders

what sin runs so deep

it even tainted

the seed in the womb.

Everyone turns

their eyes away,

not wanting to look

on the luckless one

and maybe be marked

by his sightlessness.

As a child, I didn’t know what I lacked.

I felt the closed-in, lowering gloom

that you call ‘dark’, and the lifting, expanding,

opening up, the radiance of ‘light’.

I felt the sun rise, when the world sang for joy,

and the chill as a shadow crossed its face.

Light streamed to me from my mother’s face,

her smile, her laugh, her gentle kiss.

Darkness fell when she turned from me

with silent tears, my future her grief.

My father illumined my mind with words,

opening to me the book of our people,

the story of how God called all things

to be and become, beginning with light.

He told how that light was so often lost –

obscured in the foolish hearts of men,

exiled from Eden for doubting God’s love,

losing faith in the wilderness,

blindly stumbling after false gods.

But the light will come to us again.

He will always be there, beyond the clouds,

creating, illumining, turning his face

to shine upon us,

calling us

to remember our name,

to lift up our hearts,

to ourselves become light.

My father taught me to stand upright

in spite of the weight of my destiny,

accepting my fate as a sign of trust.

So what if I couldn’t live on my own,

and had to beg for my daily bread?

No man survives alone. We are all, every one,

beggars before the mercy of God,

dependent on grace, and may God help

the one who is blind to that truth.

That’s what I tried to show my people

as I sat each day by the side of the road,

my bowl held open

to heaven’s gifts.

But their eyes were closed.

They didn’t see

the sun that had risen in their midst,

the light of the world,

the face of God.

I wouldn’t have asked him for sight for myself.

I was used to the dark, and it suited me.

I could wait for the day when all things would cast off

their earthly garments, and stand in his light.

But I could see

he wanted to show them –

the ones whose hearts

were not all stone,

the ones who might yet

be brought to the light

by seeing a blind man

seeing again.

So I called to him, as he called me.

I threw off my covering and leapt into light,

following him on his way into shadow.

Let the blind man die.

Let him be reborn,

made new in a new world,

called by the Word

that created light:

Let us be…