Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. I’ll subscribe you via Mailchimp for the weekly or email you directly for the daily (your choice). Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone.

Tuesday

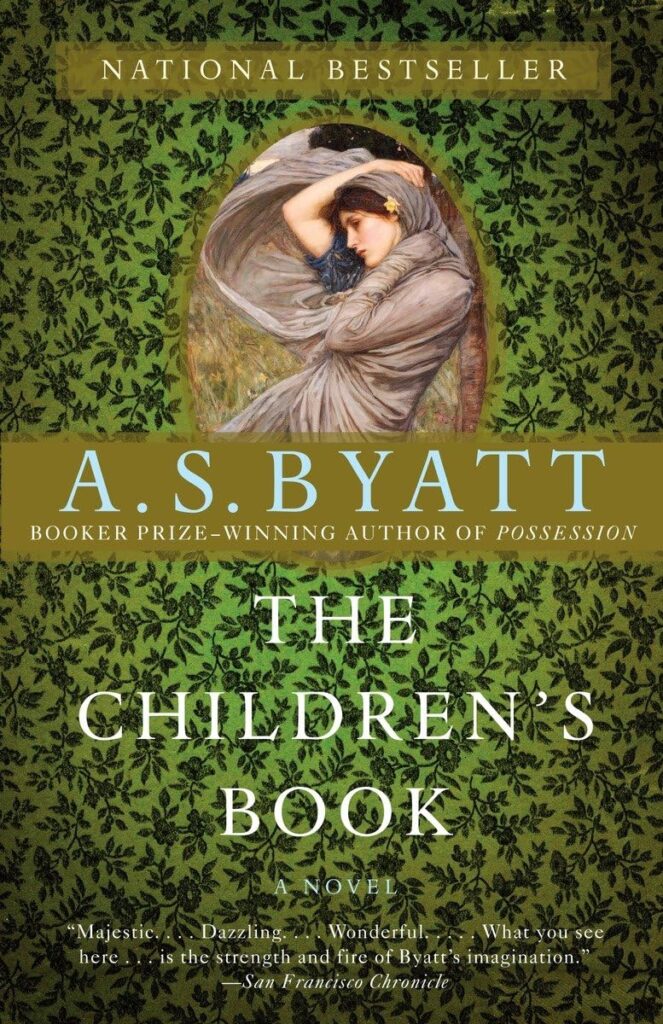

I’m currently immersed in A.S. Byatt’s The Children’s Book, which I first read in 2012. This time the novel has sent me spiraling into my past for reasons I share with you today.

Set mostly in the latter years of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th (up through World War I), Children’s Book takes as its focus the family of Olive Wellwood, who is loosely based on children’s author Edith Nesbit. My father read to us Treasure Seekers, Wouldbegoods, New Treasure Seekers, and Five Children and It, and I would later add The Railway Children, The Phoenix and the Carpet, and The Story of the Amulet to the E. Nesbit books I read to my own children. They made a deep impression on me, and one reason I sign off my weekly newsletter with “Good reading” is because I remember how the Bastable children in Treasure Seekers are always quoting the sign-off in Kipling’s Jungle Books: “Good hunting.”

There’s one scene that has haunted me ever since I first read the novel in 2012. Tom, who is Olive’s golden child and the model for her story about a boy who has his shadow stolen, is sexually molested and brutally bullied by senior students when he is sent off to boarding school. Seeking to hold on to his innocence, Tom runs away from the school, and for weeks his family doesn’t know if he is alive or dead. When he finally returns home, he retreats into the idyllic natural landscape that surrounds the family house. From then on, he makes a determined effort to hold on to his innocence, resisting family pressure to study for his exams and go off to college.

My father Scott was a kind of Tom. Unlike his two older brothers, who were outgoing and successful in sports, my father was sickly and shy. My grandmother, born in 1886 in England and a veritable angel of the house, dressed him as Little Lord Fauntleroy when he was small. (I have a picture of him in velvet with a lace collar.) He was more drawn to her and his grandmother Sarah Ricker than to his father, who worried that he wasn’t masculine enough. Scott wrote poetry, drew pictures, and was an ardent bird watcher. He would eventually go on to become a French literature major in college.

Throughout my childhood, I remember my father saying that the worst thing in the world was “the desecration of innocence,” and Byatt’s novel is bringing clarity to what he meant by that. The book sees the late Victorian and Edwardian ages as a time of innocence where people didn’t reveal their innermost secrets but put their energy into being polite and well-mannered. Better to close one’s eyes to dark realities, such as child abuse and infidelity, than cause a social scene. As Byatt writes of Olive at one point,

Things had always been behind thick, felted, invisible curtains, or closed into heavy, locked, invisible boxes. She herself had hung the curtains, held the keys to the boxes, made sure that the knowable was kept from the unknown, in the minds of her children, most of all. And now she knew that grey, invisible cats had crept from their bags and were dancing and spitting on stair-corners, that curtains had been shaken, lifted, peeped behind by curious eyes, and her rooms were full of visible and invisible dust and strange smells.

And because she is an author, Oliver finds a way to transform this into fantasy narrative:

She was rather pleased with all these metaphors and began to plan a story in which the gentle and innocent inhabitants of a house became aware that a dark, invisible, dangerous house stood on exactly the same plot of land, and was interwoven, interleaved with their own. Like thoughts which had to stay in the head taking on an independent life, becoming solid objects, to be negotiated.

One sees this longing for innocence, for not knowing, in the popularity of the children’s fiction of the time. In addition to the E. Nesbit books, there were The Jungle Books (1894), Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit (1902), James Barrie’s Peter Pan; or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up (1904), Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows (1908), and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Secret Garden (1910).

My father, who was born in 1923, was raised on these books, and he then read them to me and my brothers as we were growing up—up through middle school. Reading took the place of television for us, and I can see how the novels allowed my father to revisit his own childhood innocence.

As the first born, I particularly got caught up in this innocence drama. I was born in 1951, six years after my father returned from World War II, and my mother tells me that he was enthralled with having a child after not being sure what to expect. Although he hadn’t been in combat, he had witnessed horrors, most notably the Dachau concentration camp three days after it was liberated. Indeed, it became his job, in 1945, to take German civilians on required tours of the camp to show them what their government had done. He was 22 at the time.

In the books he read us, I noted that he hated endings where children leave the fantasy worlds they inhabit, as occurs to Wendy at the end of Peter Pan and Christopher Robin at the end of House at Pooh Corner. Meanwhile, he filled our childhood with games, in which he fully participated. In fact, he extended this to the entire faculty at the University of the South. Each year following graduation, he and my mother held a large party of over a hundred. The house he built for the occasion (which I have inherited) has a shuffleboard court down one side, a deck on the roof for playing badminton, a sunroom for playing ping pong and foosball, and a horseshoe court out in the yard. Faculty got the opportunity to be children again when they attended.

From all this I intuited, early on, that I was supposed to remain innocent for as long as possible. I consciously worked on it, closing my ears to the profanities and dirty jokes of my classmates and shying away from rock music. I chose instead to immerse myself in the fantasy worlds of George MacDonald, J.R.R. Tolkien, and C.S. Lewis.

In my book I’ve written how I loathed J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, assigned to me in sophomore English, because of the way he enters the adult world. It was only years later that I realized that Holden has the same longing I did, which is for his sister Phoebe and him to remain innocent. He fantasizes catching little children as they run through tall rye grass, saving them from growing up.

The end of Edwardian innocence was World War I, just as the end of my father’s innocence was World War II. It took me a while before I realized that I myself had to grow up. (The prospect of being drafted into the Vietnam War played a role.) And even though I did make my piece with adulthood, I relived my childhood by reading to my own children deep into their childhoods and teaching courses in literary fantasy.

The E. Nesbit character in the book imagines her child without a shadow—in other words, a perpetually golden child—but as Jung teaches us, we all have a shadow side. If we wish to grow into mature and well-balanced people, we must open ourselves to it, not wish it away. Because I wished to please my father, I struggled with this issue for a long while.

As frustrating as he could be, however, I find myself deeply grateful to my father for the world he created around for me and my brothers. If there were blindnesses, they were benign. He died 13 years ago, at age 90, and thanks to Byatt’s novel the memories have come flooding back. I miss him terribly.