Wednesday

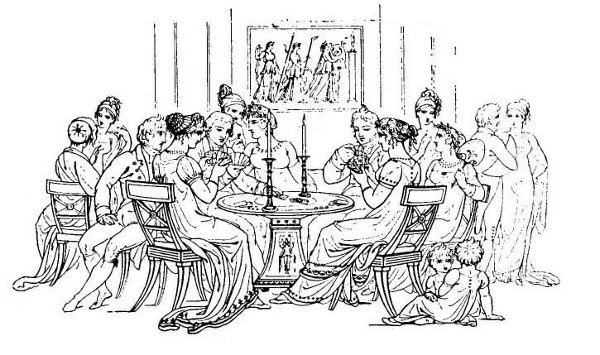

I’m preparing for a session tomorrow where I will teach Vanderbilt Library patrons about Speculation, the card game played in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Today, therefore, you get my preliminary notes.

I’ll have to admit to the group that I’m not an expert on cards. I have, however, long been fascinated by how authors (not only Austen) make thematic use of card games. To better understand the Mansfield Park characters, it helps to know the rules of Speculation and why different players play it as they do.

One can say this of all the card games that show up in Austen’s novels. All but Lady Susan make some mention of cards. Sometimes cards seem to be a married guy thing: Mr. Allen in Northanger Abbey prefers cards to dancing and leaves the ladies to their own devices. So does the crass Mr. Hurst in Pride and Prejudice, and when he can’t find people to play with, he sulks by lying down on the couch. In Emma, there are agonized discussions about how to set up an evening affair so that dancers and card players have separate spaces. Mr. Wodehouse plays whist whenever Emma can set up a foursome, although he foregoes it when he wants to spend time talking to his other daughter during a visit.

And then there’s high stakes gambling. Wickham’s villainy is finally confirmed when it’s learned that he is a gamester. Tom Bertram in Mansfield Park also is an enthusiastic card player, which may explain how he runs into financial trouble, costing his brother a parish.

But women play cards too. Although Elizabeth turns down a card game in Pride and Prejudice, it’s because the Bingleys are play for more than just pennies. Elsewhere we see her playing lottery, a game that requires minimal attention and that she uses as cover to talk to Wickham.

Quadrille, on the other hand, discourages outsiders because of its complex rules, which is why the snobby Catherine de Bourgh insists upon it in Pride and Prejudice. Because of its complexity, it would evolve into the simpler whist, which is what the Bennets play, as does Mr. Wodehouse.

Jane Bennet, meanwhile, knows that she and Bingley are right for each other because their simple natures prefer Vingt-un to Commerce, the forerunners of blackjack and poker.

Cards is an ideal activity for this society because people can converse when they want and then focus on the game when they run out of things to say. It’s more entertaining than, say, conversing on the respective heights of Lady Middleton’s children.

But there’s another marker here. Attitudes towards cards seems to divide Austen’s classicism from her romanticism. The romantic Marianne detests cards, preferring piano playing. To be sure, card playing provides her with a way of interacting with Wickham when she’s in society—he cheats on her behalf—but she’d much rather be talking privately with him about their mutual love of Cowper’s poetry, say when they riding or walking. Persuasion’s Anne Elliot, an even deeper soul, prefers substantive conversations with Mrs. Smith to the vapid card parties of Bath.

A conversation about cards marks an important moment in Anne’s reconciliation with Wentworth:

“You have not been long enough in Bath,” said he, “to enjoy the evening parties of the place.”

“Oh! no. The usual character of them has nothing for me. I am no card-player.”

“You were not formerly, I know. You did not use to like cards; but time makes many changes.”

“I am not yet so much changed,” cried Anne, and stopped, fearing she hardly knew what misconstruction.

It’s worth noting also that Elizabeth never plays cards with Darcy (only with Wickham) and Emma doesn’t play them with Knightley. And while Fanny Price plays with Edmund Bertram, it’s only when he’s got his eyes on Mary Crawford. In short, when serious love is in the air, cards are out.