Wednesday

Conservative NeverTrumper Bret Stephens, with whom I seldom agree, has written a New York Times column that could have appeared in Better Living through Beowulf. In other words, Donald Trump is prompting even inveterate foes to make common cause. In this case, the issue is immigration.

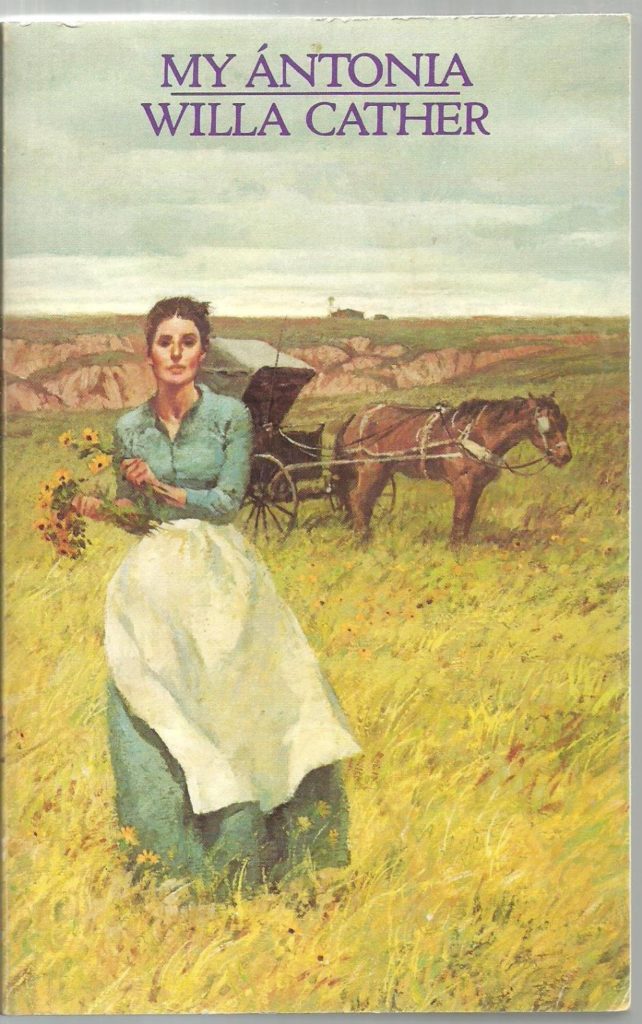

As Stephens sees it, Willa Cather’s My Antonia tells an immigrant story that contradicts everything that Trump, Stephen Miller, and others say about those seeking to find a home in the America. It also function as a reproof to Americans who close their eyes to their own immigrant past.

Antonia Shimerda is from a family of Bohemian immigrants who come to Nebraska to escape the poverty. With an eye on Trump, Stephens points out, that

[t]hese were the people who made the Midwest great. Their English, on arrival, was generally poor or nonexistent. Their skills were often ill-suited to the needs of the places to which they came. Their religious beliefs were not those of their American neighbors. They were accused of being clannish, and they were not always grateful to be here.

Despite these obstacles, they became an integral part of America’s success story:

What hasn’t changed is that immigrants, on the whole, succeed. “Foreign farmers in our county were the first to become prosperous,” Cather’s (grown-up) narrator notes. “After the fathers were out of debt, the daughters married the sons of neighbors — usually of like nationality — and the girls who once worked in… kitchens are to-day managing big farms and fine families of their own.” Yet many of the locals saw them as “ignorant people who couldn’t speak English.”

Stephens points out their success was aided by established Americans who felt called to reach out to them:

Cather’s novel is a story of a country that can overcome prejudice. The narrator’s grandfather offers succor to the destitute Shimerdas, forgives them their debts, puts petty quarrels aside, and consoles them in their grief. After Ántonia’s father commits suicide, he prays “that if any man there had been remiss toward the stranger come to a far country, God would forgive him and soften his heart.”

Stephens brings his point home:

It’s in such moments that My Ántonia becomes an education in what it means to be American: to have come from elsewhere, with very little; to be mindful, amid every trapping of prosperity, of how little we once had, and were; to protect and nurture those newly arrived, wherever from, as if they were our own immigrant ancestors — equally scared, equally humble, and equally determined.

Immigrant literature has given rise to many of America’s most prized literary works. Whether the author is Cather, Amy Tan, Ole Rolvaag, Paule Marshall, Sandra Cisneros, Julia Alvarez, Upton Sinclair, Jhumpa Lahiri, Alice McDermott–I could go on an on–each nationality tells a version of the same story. America’s essential character is as an immigrant nation. The day we forget that will be the day we cease to be America.