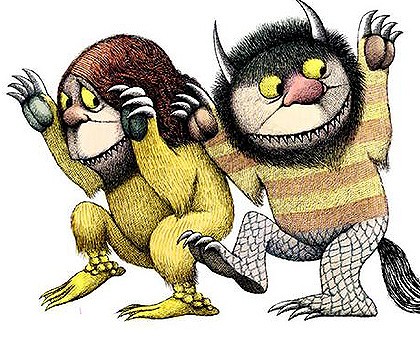

Illustration from Where the Wild Things Are

Illustration from Where the Wild Things Are

I see that Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are (1963) has been turned into a film, which has led Slate columnist Jack Shafer to revisit a controversy about the book. Apparently Sendak still can’t let go of a critique by psychologist Bruno Bettelheim.

I was surprised to learn that Bettelheim had criticized Where the Wild Things Are given that Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales shares Sendak’s respect for children. Sendak’s book acknowledges the true inner life of children, not children as they are sentimentalized by adults. Similarly Bettelheim attacks those Disney’s films that “sanitize” the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales (like “Snow White” and “Cinderella”), thereby denying children the opportunity to come face to face with their deep inner fears and desires. I would have thought that Bettleheim would welcome stories like Sendak’s.

Apparently Bettelheim was speaking about Where the Wild Things Are without having read it. Here’s what he said:

“What’s wrong with the book is that the author was obviously captivated by an adult psychological understanding of how to deal with destructive fantasies in the child. What he failed to understand is the incredible fear it evokes in the child to be sent to bed without supper, and this by the first and foremost giver of food and security—his mother.”

The moral of this is don’t talk about books you haven’t read. Sendak doesn’t underestimate the impact on the child of being sent to bed without supper. He just focuses, appropriately enough, on the rage the child feels, which is why the story speaks to so many. Bettleheim’s comment is actually useful in helping us understand the source of the rage.

If Sendak could freely depict children’s rebellious urges, it’s because the way had already been cleared for such inner exploration. I’m thinking of Dr. Seuss’s Cat in the Hat, which appeared in 1937.

Having said that, there is a significant difference between Cat in the Hat and Where the Wild Things Are. In the earlier work, “Sally and I” are guiltless of the mayhem that the cat creates, innocent by-standers who watch helplessly as their alter egos, Thing One and Thing Two, trash the house. Max, by contrast, owns his anger, becoming not only a wild thing but the king of the wild things. Where the Wild Things Are would indeed have caused a major controversy at a time when people’s ideas of children were Shirley Temple and Judy Garland.

I have written on the controversy that Maurice Sendak stirred up through his publication of In the Night Kitchen (1970). It’s one thing to admit that children can be angry, especially at the dawn of the youth revolution of the 1960’s. It’s another to admit that they have sexual feelings.

Actually, Sendak and Seuss can trace their roots back to authors of the 19th century as authors have been depicting the inner lives of children for a while, often to the consternation of parents. Lewis Carroll launches an all-out assault on moralistic poems in the Alice books, and I never realized how dangerous parents found Tom Sawyer, how radical a book it is, until my colleague and Twain specialist Ben Click pointed it out to me. More on these topics tomorrow.

One Trackback

[…] Honoring Our Inner Wild Rumpus […]