For our final Library Reading Group session of the year, we generally choose a children’s classic to honor our inner child. Sometimes actual children attend. This year we chose Charlotte’s Webb, and I hadn’t realized that it is a book about poetry saving a life.

Okay, so Charlotte is not exactly a prolific poet, limiting herself to one-word and two-word poems. She’s a minimalist, in other words. But it’s clear that E. B. White sees her as a poet. As he notes in the book’s final sentences, “It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.”

Charlotte has a special process that she goes through to produce her visual or concrete poems. She needs to be alone and she works best when she is “hanging head-down at the top of my web. That’s when I do my thinking, because then all the blood is in my head.”

Her first poem, “SOME PIG,” is a remarkable debut. People from all over the surrounding farms come to see it.

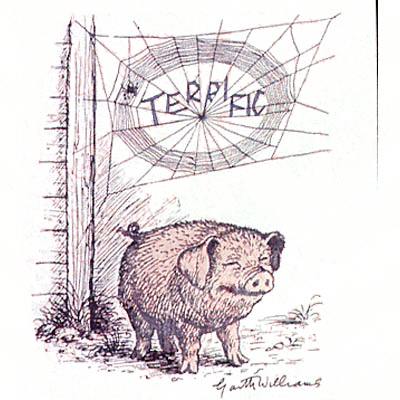

Then, to prove that she’s not a one-hit wonder, she follows it up with another sensation: “TERRIFIC.” White shows us the poetic process at work as Charlotte crafts what we could call web poems:

Now for the R! Up we go! Attach! Descend! Pay out line! Whoa! Attach! Good! Up you go! Repeat! Attach! Descend! Pay out line. Whoa, girl! Steady now! Attach! Climb! Attach! Over to the right! Pay out line! Attach! Now right and down and swing that loop and around and around! Now in to the left! Attach! Climb! Repeat! O.K.! Easy, keep those lines togheter! Now then, out and down for the leg of the R! Pay out line! Whoa! Attach! Ascend! Repeat! Good girl!

Remarkable as these efforts are, however, they don’t altogether touch on the soul of the subject. Wilbur is an endearing pig but “TERRIFIC” doesn’t really capture what makes him special.

Charlotte and Templeton the rat engage in some research to find better words, turning to Templeton’s junk pile of old newspapers. A laundry advertisement—“With New Radiant Action”—leads to “RADIANT.” Think of it as a found poem.

“RADIANT” is more precise than “TERRIFIC” but still not quite right. After asking Wilbur to leap in the air, Charlotte is forced to admit that her poem comes up short, even though Wilbur insists that he feels radiant:

“Do you?” said Charlotte, looking at him with affection. “Well, you’re a good little pig, and radiant you shall be. I’m in this thing pretty deep now—I might as well go the limit.”

The poems are having a definite impact—farmer Zuckerman decides to take Wilbur to the state fair—but it still appears that the slaughterhouse will be his future. If her work is to have the impact that she really wants it to, Charlotte will have to produce a masterpiece. She does so, coming up with “HUMBLE.”

The poem is Wilbur to the core. As Charlotte explains it,

‘Humble’ has two meanings. It means ‘not proud’ and it means ‘near the ground.’ That’s Wilbur all over. He’s not proud and he’s near the ground.

The poem also manages to reshape the narrative around Wilbur so that he can no longer be regarded as future bacon and ham. Zuckerman looks at him and says, “’Humble.’ Now isn’t that just the word for Wilbur!”

Linda Stewart, one of our discussion group members, told us that her farm family made it a policy never to name their livestock because that would make it harder to kill them. Through the aid of Charlotte’s poetry, Wilbur can now be seen as a family pet and therefore safe.

In a moment of high romanticism akin to, say, E. A. Hoffman’s Antonia killing herself by singing her final aria against her doctor’s orders (in Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffman), Charlotte expends her vital forces producing her final poem. It may kill her “mais quelle geste!” (“but what a gesture!” to quote Cyrano):

Charlotte’s web never looked more beautiful than it looked this morning. Each strand held dozens of bright drops of early morning dew. The light from the east struck it and made it all plain and clear. It was a perfect piece of designing and building. In another hour or two, a steady stream of people would pass by, admiring it, and reading it, and looking at Wilbur, and marveling at the miracle.

She then dies but she has saved a life. Don’t underestimate the dedication of poets.

One other thought: I can think offhand of two literary instances, one positive and one negative, where poets are compared to spiders. One is the creator of the world and the poetic muse in Leslie Marmon Silko’s novel Ceremony. Silko is Laguna Pueblo:

Ts’ its’ tsi’ nako, Thought-Woman,

is sitting in her room

and what ever she thinks about

appears.

She thought of her sisters,

Nau’ ts’ ity’ i and I’ tcs’ i,

and together they created the Universe

this world

and the four worlds below.

Thought-Woman, the spider,

named things and

as she named them

they appeared.

She is sitting in her room

thinking of a story now

I’m telling you the story

she is thinking.

The negative image comes from Jonathan Swift’s Battle of the Books, for whom spiders are a metaphor for those self-indulgent artists who try to spin everything out of their own bellies.

The benevolent and self-deprecating Charlotte fits the Silko rather than the Swift image.

One Trackback

elevators For kids

Charlotte