Wednesday

In response to a recent post on how “Great Novels Tell Uncomfortable Truths,” reader David Rothman, himself a novelist, alerted me to the problems he has encountered getting an uncomfortable novel about Congolese child soldiers published. This despite selling six earlier books to publishers. Novels can sometimes break through where news stories cannot, but they have to at least see the light of day.

In probing the reasons for Drone Child’s current challenges., David encountered the problem of self-censorship—which is to say, teachers who are afraid of how administrators might respond if they assigned the book or even purchased it for the school library.

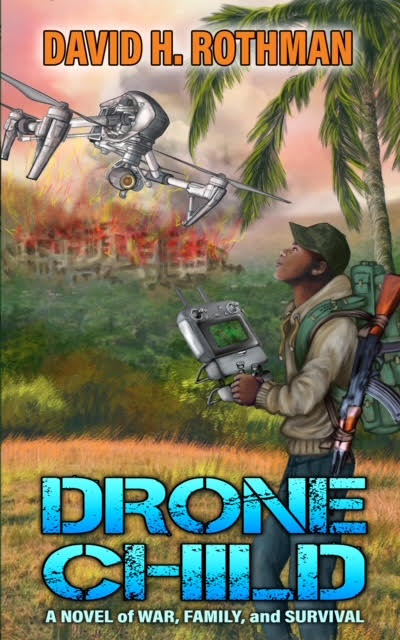

Fortunately, one can self-publish, and Drone Child is now available on Amazon. But David’s experience still raises troubling questions. I invited him to tell his story, which you read below. In addition to writing novels, David is a former poverty beat reporter, has written several books of non-fiction, advocates for libraries, and publishes the TeleRead.org ebook site. His previous novel was The Solomon Scandals. . He is reachable at davidrothman@pobox.com

Guest Post by Novelist David H. Rothman

While electric cars may be our future, fewer Americans might be able to afford them because the Chinese have cornered so much of the market for the cobalt used in batteries. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, as reported in a recently published New York Times series, is a major source. But we should care about the Congo also for humanitarian reasons, given that the country is torn apart by conflict minerals and intertribal rivalries. This on top of the Congo’s crime and poverty!

Now, suppose a novel might prod at least a few voters out of their apathy. My novel Drone Child tackles the issues. In it, a pair of 15-year-old twins flee their village to escape gun-worshipping rebels who make children kill their own parents. Child has sex and violence. But how could one write about wars in the real Congo—the rape capital of the world—without them?

Child also comes with a sympathetic, upbeat hero who belies the “s-hole country” stereotypes. Lemba not only survives but prospers. He ideally can serve as a role model for some disadvantaged young people of all races, even though he himself offers a caveat on page one of his war memoir: “Of course, I was lucky—fate could easily have flattened me. All I could do was try.”

Two Congolese have vetted Drone Child, one of them a civic leader and a winner of a prestigious Mandela Washington Fellowship sponsored by the U.S. State Department. They believe it is both highly readable and authentic enough to merit publication in the DRC itself. A Congolese war refugee who lived out real-life nightmares similar to those of the protagonist agrees.

As the author I’m hardly disinterested, but shouldn’t Drone Child at least have a chance to beat the scary odds and reach the right readers—especially bright young people able to identify with the techie brother and his gifted songbird of a sister? Child even comes with a downloadable discussion guide for book clubs, schools, and libraries. An author’s note delves into facts vis-à-vis fiction.

In my book, soldiers cut off and eat a woman’s arm. It happened in the real Congo, complete with a promise to dine on her husband’s heart. Holocaust histories can come with graphic references to lampshades made of white human skin. Shouldn’t we care regardless of the races and countries of the victims? And how about some of the most timeless plays and novels? If Romeo and Juliet can die suicides and Macduff can behead Macbeth and a mother in Beloved can kill her baby—well, must we be so protective of delicate minds?

Unfortunately, many say yes. As one retired high school teacher told me, “I’d have been fired if I taught your book.” She loved Child but could vividly picture herself broke and begging on the streets if she shared her enthusiasm with 12th graders. Mind you, this was in a liberal state. A former substitute in Texas more or less told me the same.

By contrast, one of my fact-checkers in the Congo said Child was just right for schools there. No, I won’t condemn U.S. teachers based on the just-given examples. My sample is far too small, and of course, teachers are simply captives of administrators, who are themselves answerable to politicians. As if that is not enough, some educators have received death threats for the books they’ve taught. Is my book worth a teacher or librarian risking his or her life?

Let’s also remember some other nuances. There is a difference between a book being compulsory reading for 10-year-olds—and no, I’m not calling for Child to be—and its simply being available in a school or public library for high school seniors or adults. Education Week has just run an excellent interview with Jennisen Lucas, the president of the American Association of School Librarians in which she explores some of the subtleties of the censorship controversy.

I’ll keep an open mind. Still, if nothing else, the reactions of the retired teacher and the former substitute hint of the challenges ahead for Child in schools and libraries amid the current censorship mania.

One other reason could be that the book is self-published—hardly an accident, considering the aversion of some publishers and agents to my subject matter. The publisher of my first novel, The Solomon Scandals, rejected Child. A Yale-educated lit grad working for the Washington City Paper had praised Scandals for the “same dark zeal Hammett held for Frisco or Chandler had for Los Angeles.” But the publisher apparently considered the zeal in Child itself to be too dicey.

“It sounds incredibly important and meaningful (and wow that opening scene, that’ll stay with me), but I’m afraid that by the sound of it, it’s going to be a bit too thematically dark for me right now,” one New York literary agent wrote. At least she was gentle with me. Another agent, whom I’d known for years on a mutual first-name basis, suddenly went formal with a “Dear Mr. Rothman.” Publishers and agents should serve as gatekeepers, but could this avoidance of “thematically dark” topics at times get in the way of books legitimately exploring topics about which more Americans should know as both humans and citizens? De facto self-censorship?

Alex Haley’s Roots is said to have been rejected 200 times. At least partly due to the book business’s genteel racism (still around despite reforms), more than a few publishers have spurned Black-written novels that would go on to become best-selling classics. Commercial reasons undoubtedly were among those given. But what’s the cart and what’s the horse? Could kowtowing to American racism be another form of censorship?

Regarding Amazon, I’m of mixed mind. Thank goodness it can help me bypass censors and self-censors. On the other hand, Amazon so far has failed me as a marketing tool. Child went on sale there earlier this year with a less enticing cover and a different title, but another challenge is that few customers now care about the Congo and child soldiers. (I base this on the number of searches for related terms and ad-response statistics.) Racism at work?

In response, we should be pushing for more books encouraging Whites to empathize with people of color, both here and abroad. Publishers, librarians and others should be trying harder to enlarge the universe of readers among minorities. The very books that most offend bigots at times may be useful in doing what Child may do for certain young people of all colors—provide them with positive role models.

Amazon’s big goal is to cater to the consumer-reader, but that philosophy isn’t necessarily good for books that address disturbing social issues, including novels. Robin Bates got at what we lose when he criticized a guest MSNBC commentator for asserting that the fuss over Toni Morrison’s book was

overblown because Beloved is only fiction. In saying so, he underestimates the disruptive potential of novels. Indeed, Beloved is meant to disturb readers, Black as well as White. Great literature is often great because it disturbs.

I’ll leave it for others to decide if Drone Child is great or even just good, but I would never deny that my book disturbs, as well it should—given the atrocities happening today in the Congo.