Sports Saturday

In one of the smartest sports articles I have seen in a while, ESPN’s on-line magazine recently turned to Moby Dick to better understand the enigmatic Chris Andersen of the Miami Heat. Known as “Birdman,” Andersen was instrumental in the Heat’s championship last year, bringing to the floor tremendous energy and a high shooting percentage. The Heat will need all of that energy in their title quest this year.

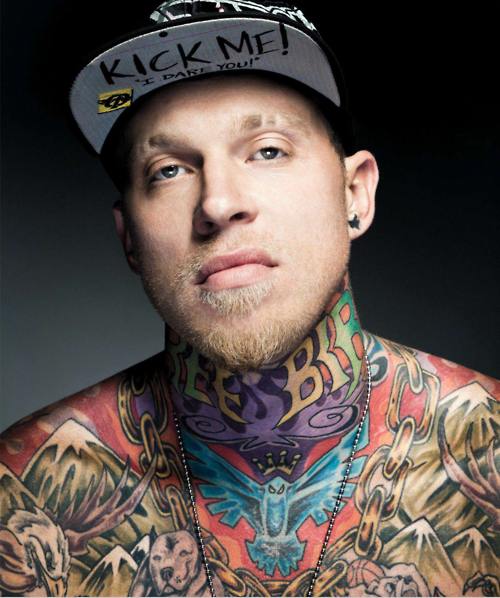

But Andersen is best known for his tattoos, which cover almost his entire body. To say that he is a colorful character is, in this case, literally true.

The tattoos are the starting point for author Jeff MacGregor, who begins his article with Ishmael’s description of the harpoonist Queequeg:

“And this tattooing had been the work of a departed prophet and seer of his island, who, by those hieroglyphic marks, had written out on his body a complete theory of the heavens and the earth, and a mystical treatise on the art of attaining truth; so that Queequeg in his own proper person was a riddle to unfold; a wondrous work in one volume; but whose mysteries not even himself could read, though his own live heart beat against them; and these mysteries were therefore destined in the end to molder away with the living parchment whereon they were inscribed, and so be unsolved to the last.”

And now here’s MacGregor, first describing Andersen’s own tattoos and then attempting to unfold Andersen’s riddle:

Even in the half-light of the tent, the ink tells his story. But tells it only to him. The player at the rim, in the clouds. The great crowned skull. The chains and the ideograms. The Celtic cross. Pit bull and bulldog. Real Rock N Roll. Good ol boyz. Dead End. Honky-tonk. Country. Screw you. Punk ass. Dollar sign behind the right ear; 11 behind the left. The Viking. The bat. Stars on his earlobes. Swifts and swallows flying up out of his shoes. Phoenix rising at his throat. That Free Bird turtleneck, neon green and acid yellow on a field of purple flames. All of it under skin so pale it’s luminous. And the wings. Those wings.

His arms and legs and back and chest are stitched with ink, with story, but in a secret language. He commemorates adversity and what didn’t kill him. He records his happiness. He just doesn’t say how. Which image stands for what? Which for abandonment or a broken heart? Which for anger or loneliness or joy? Which is the picture of his sadness, his ambition, his regret? Which defines him? Even in this unknown language, he’s no hero, and every story is true and not true, because everything is complicated and because the ink hides as much as it reveals. All the success and every failure, crowded now with line and color, has been made beautiful. “It is what it is,” says Chris Andersen. He is half a mystery, even to himself.

I love the idea that the tattoos hide as much as they reveal. Or as MacGregor puts it:

You can’t miss him. But because he’s wrapped in a kind of camouflage, you wonder whether anyone can really see him, either.

And further on:

The tattoos are reminders, cues and prompts right out of Memento. But the ink is also a way to hide in plain sight. A disguise. A body double. Armor. As much an erasure as a declaration, Birdman is a fiction. A character. He tells his story at the same time he edits it at the very moment he hides inside it. New ink covers old. Life is pain.

And then the following insight:

[T]here’s no denying Chris Andersen is a canvas on whom every one of us paints. And like every other American, he lives in a constant state of personal reinvention. His is just easier to see.

MacGregor has grasped Melville’s insights at a deep level. In certain ways, Melville is America’s ultimate existentialist author, a Kafka before Kafka. Identity is never stable for him but always shifting. In certain ways, he is a complement to Walt Whitman. Whereas Whitman embraces the multitudinous identities that comprise America, Melville questions each and every one of these identities.

I particularly like how MacGregor points out Andersen’s luminous pale skin (his father was Danish), which recalls Melville’s famous chapter on “the whiteness of the whale.” It is Moby Dick’s whiteness that most appalls Ishmael:

Aside from those more obvious considerations touching Moby Dick, which could not but occasionally awaken in any man’s soul some alarm, there was another thought, or rather vague, nameless horror concerning him, which at times by its intensity completely overpowered all the rest; and yet so mystical and well nigh ineffable was it, that I almost despair of putting it in a comprehensible form. It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me. But how can I hope to explain myself here; and yet, in some dim, random way, explain myself I must, else all these chapters might be naught.

While admitting that the color white is often a positive sign, associated with innocence and purity, Ishmael notes that it can also signal a terrifying void. This may be key in understanding Andersen’s attraction to tattoos. Here’s part of Ishmael riff on whiteness:

Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way? Or is it, that as in essence whiteness is not so much a color as the visible absence of color, and at the same time the concrete of all colors; is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows — a colorless, all- color of atheism from which we shrink? And when we consider that other theory of the natural philosophers, that all other earthly hues — every stately or lovely emblazoning — the sweet tinges of sunset skies and woods; yea, and the gilded velvets of butterflies, and the butterfly cheeks of young girls; all these are but subtle deceits, not actually inherent in substances, but only laid on from without; so that all deified Nature absolutely paints like the harlot, whose allurements cover nothing but the charnel-house within; and when we proceed further, and consider that the mystical cosmetic which produces every one of her hues, the great principle of light, for ever remains white or colorless in itself, and if operating without medium upon matter, would touch all objects, even tulips and roses, with its own blank tinge — pondering all this, the palsied universe lies before us a leper; and like willful travelers in Lapland, who refuse to wear colored and coloring glasses upon their eyes, so the wretched infidel gazes himself blind at the monumental white shroud that wraps all the prospect around him. And of all these things the Albino Whale was the symbol. Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?

So maybe Andersen, whose rough life is outlined in the ESPN article, feels naked and empty in his white skin. Maybe he experiences, as some level, an existential emptiness—a “dumb blankness”—which he tries to cover over with color. If so, does he realize that such colors may be just “subtle deceits” that hide the “charnel-house within”?

Maybe he does because, as MacGregor mentions in passing, Andersen is also reading Buddhist philosophy, which provides a much different interpretation of emptiness. Buddhists believe one should empty the mind to move beyond the self and find peace. Rather than writing meaning upon the abyss, they declare that the the idea that we can impose meaning is illusion. Maybe at some level Andersen gets this. As MacGregor reports,

Andersen, who can never escape your notice, succeeds in part by setting aside his identity and his past, just like Ray Allen, two lockers over. “We’re devoid of ego. We’ve been around long enough to understand where we fit in, and we have to find a way to fit in by adding whatever is missing. As veterans you do whatever you do to help the team win.”

In other words, no “I” in team, no existential crisis in whiteness, and mystic body runes that spell out the enigma of life.