Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

I’m reposting an essay written seven years ago when someone else close to me was dying of cancer. Lucille Clifton knew whereof she spoke when she wrote these poems.

Reposted from July 5, 2017

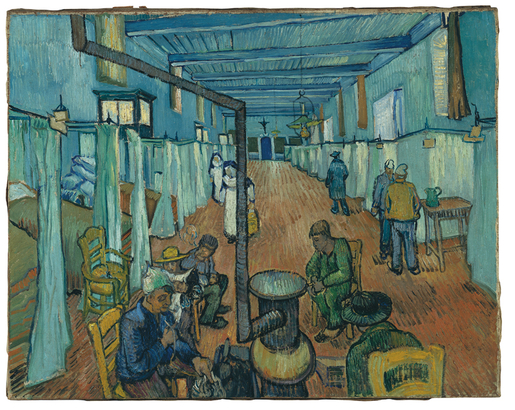

Lucille Clifton’s cancer poems mean a lot more to me since I spent several days in a Bronx oncology ward with my friend Rachel Kranz, who is battling ovarian cancer. I promised Joyce A. Asante, her wonderfully supportive nurse, that I would write a post on those poems so here it is.

Clifton became acquainted with the illness when her husband Fred, who didn’t smoke, came down with lung cancer and died at 49. In Next (1987), Clifton writes both about Fred’s cancer and that of other patients she met in the cancer ward. The book gets its title from a two-line poem that reminds us that the bell tolls for all of us:

the one in the next bed is dying.

mother we are all next. or next.

Clifton is struck by how cancer cells appear to “bloom,” normally a positive, life-affirming process. Not in this instance, however:

something is growing in the strong man.

it is blooming, they say, but not a flower.

he has planted so much in me, so much.

I am not willing, gardener, to give you up to this.

The cancer treatment process seems to violate the natural order in numerous ways, most notably by injecting poisonous medicines into the body. Instead of mothers with nurturing remedies, Clifton sees cold God-like doctors administering chemicals to cure the disease. In “chemotherapy,” she cries out that none of it makes sense:

my hair is pain.

my mouth is a cave of cries.

my room is filled with white coats

shaped like God.

they are moving their fingers along

their stethoscopes.

they are testing their chemical faith.

chemicals chemicals oh mother mary

where is your living child?

In a poem dedicated to 21-year-old “joanne c.,” probably a patient that Clifton met in the ward, Clifton gets at another confusing aspect of cancer: the body is at war with itself. (The Gettysburg reference signals that it’s a civil war.) Also contradictory is cancer’s “murderous cure”:

the death of joanne c.

11/30/82

aged 21

i am the battleground that

shrieks like a girl.

to myself i call myself

gettysburg. Laughing,

twisting the i.v.,

laughing or crying, i can’t tell

which anymore,

i host the furious battling of

a suicidal body and

a murderous cure.

Clifton is struck by how the very word “cancer” can reduce us to a helpless state. In “incantation,” she imagines that an evil magician has transformed the patient into a puppet. Unlike my friend Rachel, who is an exemplary and therefore difficult patient because she demands that every procedure be explained and justified, the patient in Clifton’s poem has surrendered her autonomy:

incantation

overheard in hospital

pluck the hairs

from the head

of a virgin.

sweep them into the hall.

take a needle

thin as a lash,

puncture the doorway

to her blood.

here is the magic word:

cancer.

cancer.

repeat it, she will

become her own ghost.

repeat it, she will

follow you she will

do whatever you say.

Rachel and I were both struck by how many of the hospital’s doctors engage in power struggles and prefer docile patients to questioning patients. Clifton is never one who will do “whatever you say,” however, and she insists that we own our own emotions. In “leukemia as white rabbit,” she draws on Alice in Wonderland to show a patient acknowledging just how “furious” she is.

Alice encounters the White Rabbit and his pocket watch at the start of her adventures and is struck by his obsession with time. Time, of course, being of paramount importance to one who is dying. To set up the poem, here are a couple of the relevant passages from Alice:

[The White Rabbit] came trotting along in a great hurry, muttering to himself as he came, ‘Oh! the Duchess, the Duchess! Oh! won’t she be savage if I’ve kept her waiting!’

and

[I]n a very short time the Queen was in a furious passion, and went stamping about, and shouting ‘Off with his head!’ or ‘Off with her head!’ about once in a minute.

leukemia as white rabbit

running always running murmuring

she will be furious she will be

furious, following a great

cabbage of a watch that ells only

terminal time, down deep into a

rabbit hole of diagnosticians shouting

off with her hair off with her skin and

i am i am i am furious.

I can testify, from watching Rachel go through the medical system, that “rabbit hole of diagnosticians” is a perfect description. Each department had its own theory of what was wrong with Rachel and what needed to be treated first—after the Emergency Room, she went first to the cardiac ward and then to the oncology ward, which is probably where she should have been from the first.

In the face of institutional anonymity, Clifton has a fantasy of a powerful and positive incantation, unlike the disempowering “cancer” incantation of the doctors. She imagines her mother, clad as a powerful witch, incanting the words she most needs to hear:

enter my mother

wearing a peaked hat.

her cape billows,

her broom sweeps the nurses away,

she is flying, the witch of the ward, my mother

pulls me up by the scruff of the spine

incanting Live Live Live!

Living, to be sure, may not be an option, as it wasn’t with joanne c. In that instance, a dignified surrender will do. The blood as a white flag may be a reference to declining white blood count:

the message of jo

my body is a war

nobody is winning

my birthdays are tired.

my blood is a white flag,

waving.

surrender,

my mother darling,

death is life.

Clifton may, in this acceptance of death, have in mind a poem by Mary Oliver, who was a friend. The influence goes back and forth as Oliver herself borrows Clifton’s image of bones, which appear throughout her poetry as a metaphor for that which is foundational. In “In Blackwater Woods,” Oliver tells us how we should live and how we should die:

To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go,

to let it go.

To sum up the trajectory of this post, Clifton moves from confusion to anger to acceptance. The acceptance extends not only to the patient but to those left behind. As she imagines Fred sending her messages, she picks up one that is particularly important:

the message of fred clifton

I rise up from the dead before you

a nimbus of dark light

to say that the only mercy

is memory,

to say that the only hell

is regret

Regret grows out of anger, memory out of love. Only one is healthy.