Friday

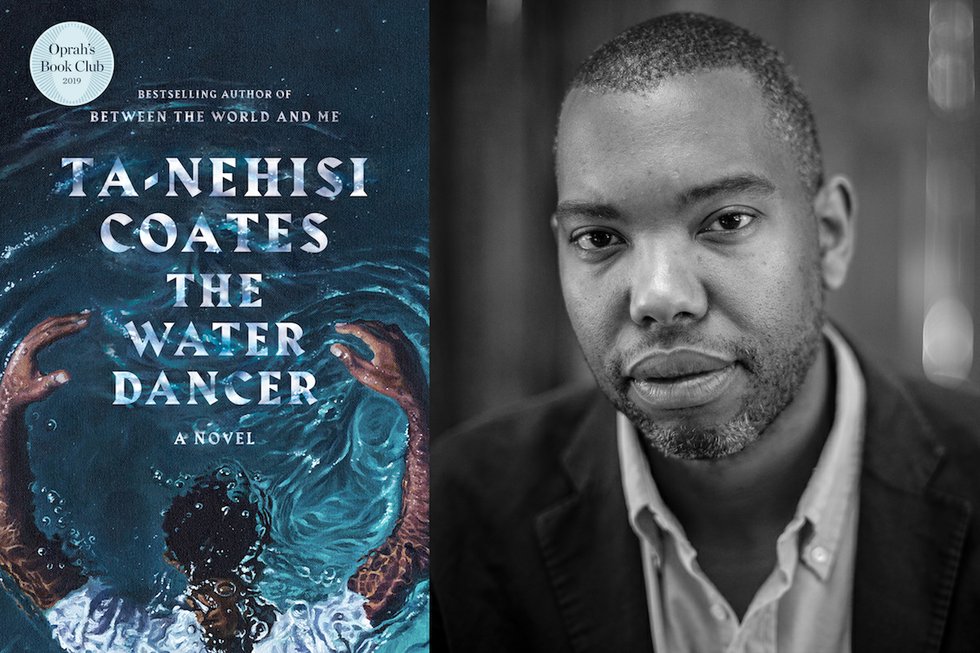

Sometimes I’ll come across a passage in a novel that throws me back in my seat. This happened recently with Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Water Dancer where the slave narrator (Hiram Walker) assesses a white plantation owner who is, contrary to appearances, a key figure in the underground railroad. If Corinne Quinn were discovered, she would lose everything—her privileged status, her wealth, probably her life. Why would a privileged woman, he wonders, risk everything for the sake of abolition?

Her own explanation is that she has grasped a truth that we also find in Hegel’s master-slave paradox, where the master is enslaved by his enslaving. Here’s how Quinn puts it:

Power makes slaves of masters, for it cuts them away from the world they claim to comprehend. But I have given up my power, you see, given it up, so that now I might begin to see.

Hiram, however, has a more cynical interpretation. While he admires Quinn’s work, he does not see it as selfless. In fact, he detects an element of vanity in it:

Corrine Quinn was among the most fanatical agents I ever encountered on the Underground. All of these fanatics were white. They took slavery as a personal insult or affront, a stain upon their name. They had seen women carried off to fancy, or watched as a father was stripped and beaten in front of his child, or seen whole families pinned like hogs into rail-cars, steam-boats, and jails. Slavery humiliated them, because if offended a basic sense of goodness that they believe themselves to possess. And when their cousins perpetrated the base practice, it served to remind them how easily they might do the same. They scorned their barbaric brethren, but they were brethren all the same. So their position was a kind of vanity, a hatred of slavery that far outranked any love of the slave.

I am reminded here of Brother Jack and the Brotherhood in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. In a dig against Communism, Ellison objects to the way that a grand ideology, even one with laudable objectives, sometimes cannot see actual people. Ellison captures this blindness by giving Jack a glass eye.

To be sure, Hiram doesn’t dismiss Quinn quite so thoroughly since he values her as a fellow combatant. In fact, I think Ta-Nehisi Coates is working through his own ambivalence about white liberal allies. On the one hand, he sees elements of privilege and selfishness behind their actions. On the other, he realizes that liberation can only be achieved if Blacks and socially conscious Whites work together.

The message for Whites is to realize, like Quinn, that you are only free when everyone is free—and to also realize that the very freedom to pick your battles is a privileged position. The oppressed don’t have that luxury.

I saw political scientist John Stoehr make a similar point recently in a column where he complained about white liberals sitting out elections. Often they don’t see the urgency of voting because their white privilege cushions them against the horrors of rightwing authoritarians coming to power:

White liberals, even now, after a preponderance of the evidence to the contrary, still believe that it’s up to the leaders of the Democratic Party to give Democratic voters a reason to vote in November. If they lose, white liberals say, the Democrats will only have themselves to blame.

What does enthusiasm have to do with self-preservation?

I don’t know about you, but when someone’s drowning, I don’t want the lifeguard asking beachgoers to inspire him to do his damn job.

In short, stop complaining that the Democratic Party isn’t catering to your every position. Stop thinking that Joe Biden has to be perfect. Forget about disillusion and consider what will happen to non-Whites if fascism prevails. And then recall the words of Saadi Shrazi, in a poem that I also owe to a Stoehr column:

To worship God is nothing other than to serve the people.

It does not need rosaries, prayer carpets or robes.

All peoples are members of the same body, created from one essence.

If fate brings suffering to one member

The others cannot stay at rest.

See people as people in their own right, not just as comments on yourself. Then let your concern for them drive your political action.