We talked about the movie Twilight in the last gathering of my British Restoration and 18th Century Couples Comedy class. That and France Burney’s epistolary novel Evelina (1775). Hang on as I spell out the connection.

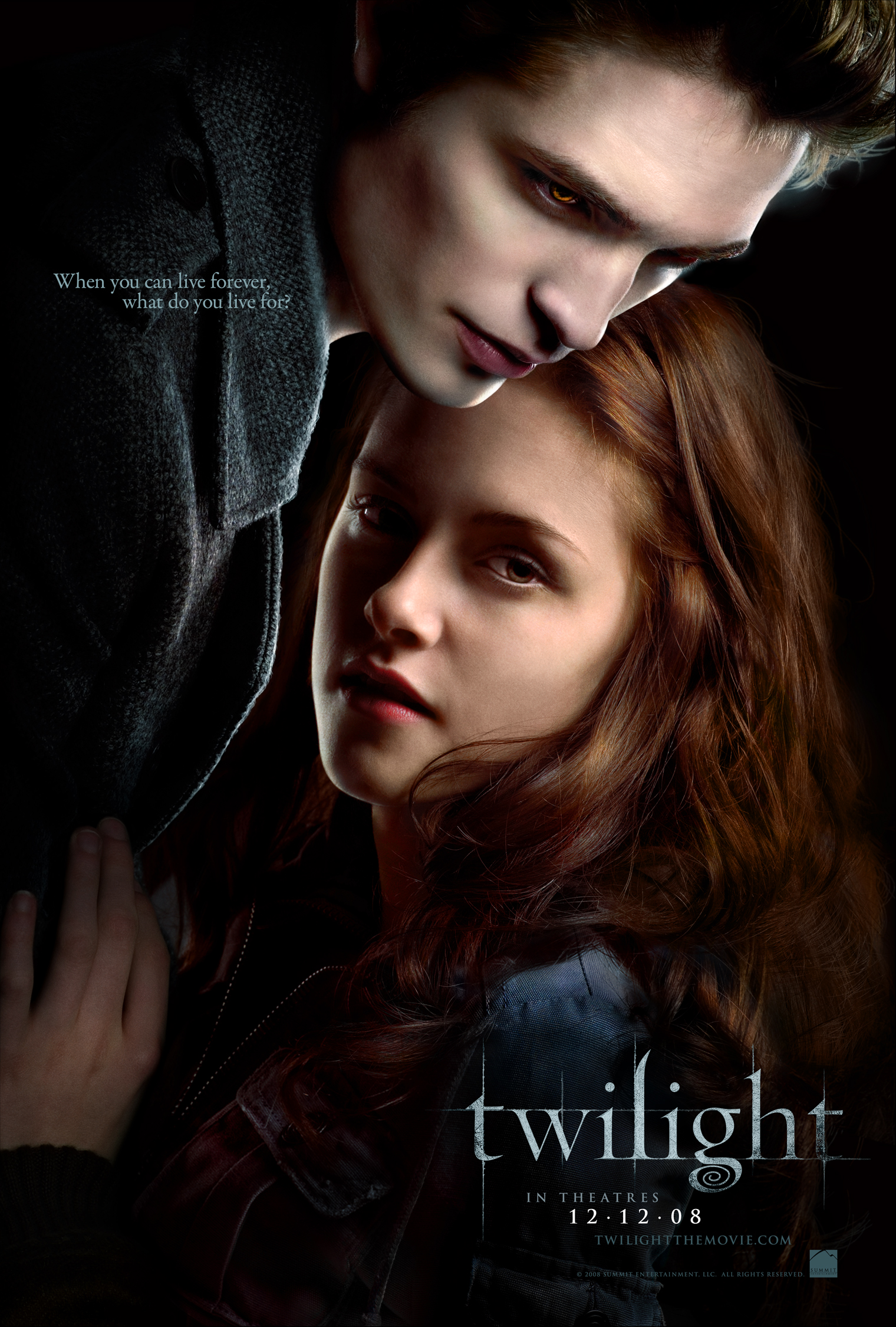

If you don’t know about Twilight, then you are probably neither a teenager nor the parent of a teenager. Twilight is the popular series about a teenage girl and vegetarian vampires that has now led to two mega-hit movies. More may be spawned. Twilight may be the biggest young adult publishing success since Harry Potter. The vampire genre has always been a coded exploration of sexual fantasies, and in the Twilight series young women have abstinence-only relationships with vampires. Which is to say, no blood sucking, just lots of flying around, lying chastely together, and talking a lot.

Twilight came up in class discussion because I was talking about how we turn to couples comedies to help us negotiate our relationship challenges and asked my students for contemporary examples. At the time, the second of the Twilight films had just been released and was selling out night after night. One of my students gave me her copy of the first Twilight film and told me to watch it.

What I saw was a heroine who feels that there is more to life than her friendly but bland high school. Something within her is demanding relationships that are more mysterious and exciting. As an adolescent, she is stepping into a brave new world of hormonal rushes, independence from parents, and identity formation. Dating the boy-next-door doesn’t seem to measure up to the occasion.

But if her monster boyfriend were too threatening, many teenagers, especially those who are younger, would be turned off. Therefore we are given a safe vampire.

Final proof that he’s safe occurs in the film’s climax (I use that word deliberately) when he squares off with a non-vegetarian vampire, who has been lusting after and chasing down the heroine. This vampire has bitten her, and the hero must suck out the poison but then stop. He doesn’t think that he can stop once he has started, but (spoiler alert) he exerts heroic self control and sucks only enough. Blood sucking interruptus. Who needs condoms?

Evelina is playing a similar game with dangerous and safe. There are two major male characters in the novel, the chivalrous Lord Orville and the licentious rake Sir Clement Willoughby (whose name Jane Austen will borrow for Sense and Sensibility). The heroine is involved in an interesting dance with Willoughby. Somehow, in spite of herself, she regularly finds herself in his power and extricates herself only with difficulty.

As my student Erin Hendrix points out, Evelina gets in trouble as long as she is ashamed of who she is. She literally runs into his arms when fleeing from social embarrassment (for instance, to get away from her vulgar lower-class cousins). Once Evelina steps into her powers and asserts herself, however, Willoughby slinks away and Orville steps forward. It is as though men seem to be predatory animals but transmute into something more manageable when a girl develops a mature and grounded identity.

This drama is particularly clear in the incident of “the letter.” Over Evelina’s protests, her cousins have invoked her name to borrow Orville’s carriage, and she is so mortified that, inappropriately for the time, she writes him a letter explaining that it was not her doing. Willoughby intercepts the letter and, signing Orville’s name, writes her a passionate love letter in response. Evelina is shocked and disillusioned. Suddenly Orville seems like another Willoughby.

But when Evelina, for the first time in the novel, stands firm in the face of Willoughby’s passionate overtures, the truth about the letter comes out and Orville becomes Orville again. Reading the transformation symbolically, Erin points out that the rake becomes the nobleman when the woman steps into her powers. Women readers could vicariously thrill to Evelina flirting with danger (but, good girl that she is, not intentionally) and then relax, reassured that her virtue will tame the man.

In short, Evelina provided young women a story that helped them give shape and direction to their lives in the 18th century, and Twilight is doing the same for young women today. Just as 18th century parents were wrong to dismiss novels as frivolous then, we would be wrong to dismiss Twilight today. The teenage years are tremendously confusing, and stories provide girls with an invaluable resource. They are reading for their lives.

2 Trackbacks

[…] eye to such concerns. I share some of my students’ responses to works in the course here, here, and […]

[…] past how young people turn to gothics to process a confusing and threatening reality (see here and here), and the New York Times extends the idea to today’s tabloid culture. Author Carina Chocano […]