Tuesday

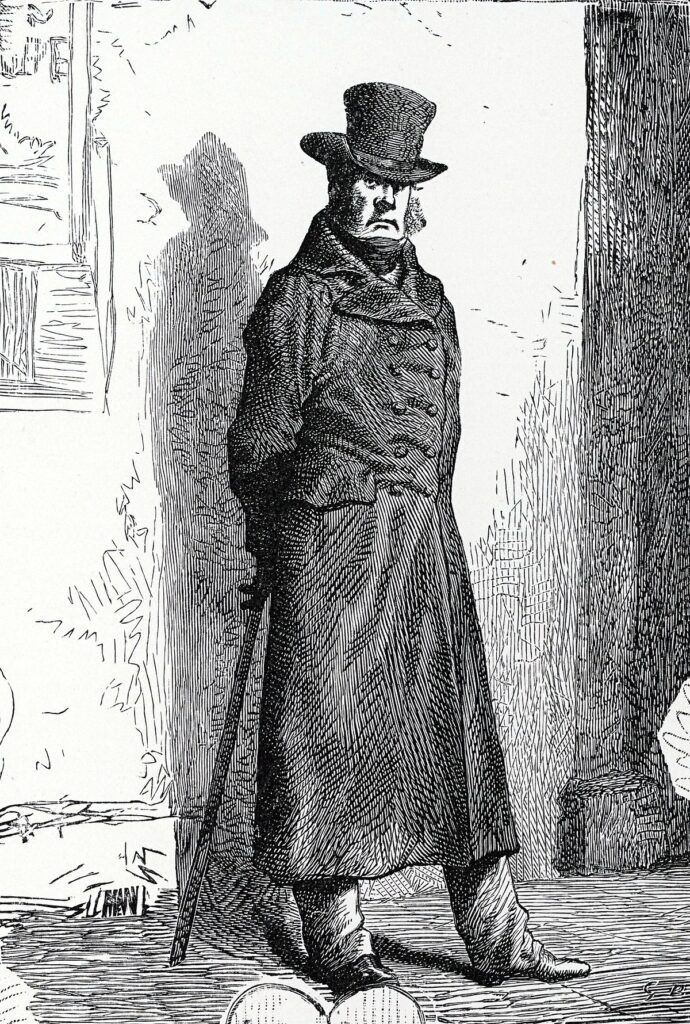

Among the many things I never thought I’d see again is the revival of Comstockery. Thanks to billionaire Leonard Leo, the man most responsible (along with Donald Trump) for stacking the U.S. Supreme Court with radical Catholics, we are in danger of resurrecting the ghost of Anthony Comstock, anti-vice activist and United States Postal Inspector from 1873-1907. I mention him in this literature blog because Greg Olear of Prevail compares him to Victor Hugo’s villainous Inspector Javert.

The Comstock Act of 1873 made it a crime to convey obscene and crime-inciting material (including abortion-related material) through the U.S. mail. Congress never got around to repealing it since, after the 1960s, it appeared an unenforceable irrelevancy, although it did receive two further blows: one in 1971, when Congress decreed it was no longer illegal to mail contraceptives, and a second in 1973, when Roe v. Wade established a federal right to abortion. Now, however, the rightwing Heritage Foundation is promising to activate it again if Trump is reelected, and Supreme Court justices Sam Alito and Clarence Thomas have spoken openly of their support.

Olear says of Comstock that he was

a wet blanket in human form—a petty, prudish, conniving, vindictive, holier-than-thou killjoy whose bizarre obsession with rooting out every “matter, thing, device, or substance” that he considered “obscene, lewd, lascivious, indecent, filthy or vile” would end up terrorizing, harming, or killing women for more than a century after his emergence onto the national scene.

Then comes the Javert comparison:

Ostensibly a vice hunter, he was, in reality, an overzealous Javert who existed to torment women—especially sex radicals and early feminists, abortionists and sexologists. He was also a huge asshole personally disliked even by his allies.

With the rightwing Federalist Society having filled many judicial appointments during the Trump years, Olear says that we have started breeding an entire legion of Comstocks:

This sad, sanctimonious schmuck would be nothing more than a footnote from an ugly, retrograde, and bygone period of American history—except that Dobbs made the laws that bear his name suddenly relevant again. With the political ascendance of reactionary religious extremists like Leonard Leo and his hand-picked and like-minded weirdos honeycombing the entire judicial branch, “Comstockery” is enjoying a revival. Leo in particular seems to be almost a reincarnation of the nineteenth century vice hunter: they are both obese, self-righteous, monomanically against abortion and contraception, politically well connected, super sneaky in their methods, and funded by obscenely wealthy conservatives.

In a follow-up blog post, Olear recounts how Comstock hounded to death (through threat of imprisonment, which led to her suicide) one Ida Craddock. Craddock’s crime was authoring The Wedding Night, which informed young brides-to-be what to expect.

Now to Hugo’s legendary vice hunter, whom the author describes as a “dog-son of a wolf”:

Now, if the reader will admit, for a moment, with us, that in every man there is one of the animal species of creation, it will be easy for us to say what there was in Police Officer Javert.

The peasants of Asturias are convinced that in every litter of wolves there is one dog, which is killed by the mother because, otherwise, as he grew up, he would devour the other little ones.

Give to this dog-son of a wolf a human face, and the result will be Javert.

Javert, like Leo, sees the world as black and white with no shading. Hugo writes,

He observed that society unpardoningly excludes two classes of men,—those who attack it and those who guard it; he had no choice except between these two classes; at the same time, he was conscious of an indescribable foundation of rigidity, regularity, and probity…

Whereas Leo views everything through the lens of his fanatical and rigid Catholicism, for Javert there is either respect for authority or there is deviation:

He was absolute, and admitted no exceptions. On the one hand, he said, “The functionary can make no mistake; the magistrate is never the wrong.” On the other hand, he said, “These men are irremediably lost. Nothing good can come from them.” …He was stoical, serious, austere; a melancholy dreamer, humble and haughty, like fanatics. His glance was like a gimlet, cold and piercing. His whole life hung on these two words: watchfulness and supervision. He had introduced a straight line into what is the most crooked thing in the world; he possessed the conscience of his usefulness, the religion of his functions, and he was a spy as other men are priests. Woe to the man who fell into his hands!

Javert, of course, lives to track down Jean Valjean, and we watch him do so relentlessly for close to 1000 pages. There is nothing in his world, however, that prepares him for the saintly man that the former galley slave becomes, a man willing to risk his own freedom to save Javert’s life. This causes such cognitive dissonance in the mind of the inspector that he throws himself into the Seine. He can handle harsh justice but not human complexity or divine mercy.

I don’t know if Leo has this capacity for introspection. What does appear to be the case, however, is that Leo and his minions appear just as determined as Javert to track down those they regard as sinners, including women who cross state lines to have abortions. State legislators in anti-abortion states have already shown their willingness to subpoena women’s medical records, monitor their periods, and imprison any who seek abortions.

Come to think of it, it’s not only a revival of the Comstock laws we should be worried about. It appears that they want to bring back female versions of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and the 1857 Dred Scott decision.