Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

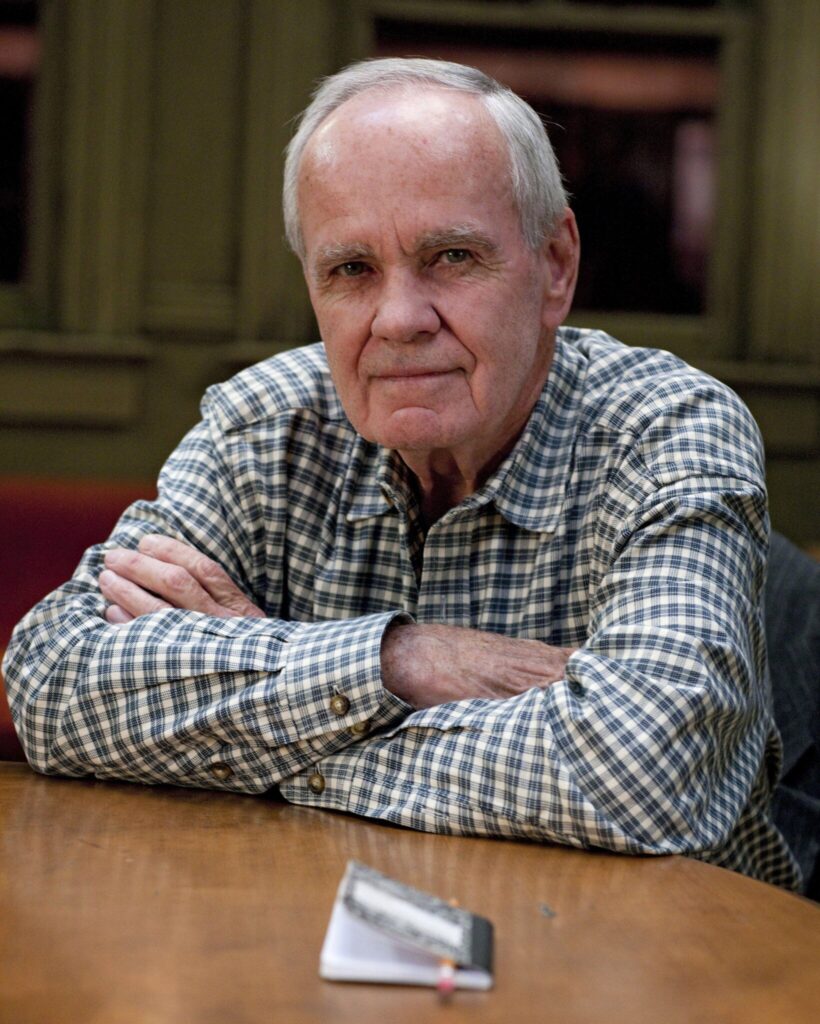

Cormac McCarthy died on Tuesday, leaving behind him works that are indelibly imprinted on my mind. From the two that most stand out to me, I conclude that there were two McCarthys—one who believed that one could hold on to one’s dignity and sense of self in the face of the grimmest of challenges, the other that we all risk being annihilated by human darkness. All the Pretty Horses is my favorite in the first category while Blood Meridian still gives me nightmares as perhaps the bloodiest book I have ever read.

In Pretty Horses, 16-year-old John Grady Cole sets off for an open-ended adventure in Mexico with his friend Lacey Rawlins. The start of their adventures, which contains a nod to the final lines of Paradise Lost (“the world lay all before them”), is positively lyrical:

They heard somewhere in that tenantless night a bell that tolled and ceased where no bell was and they rode out on the round dais of the earth which alone was dark and no light to it and which carried their figures and bore them up into the swarming stars so that they rode not under but among them and they rode at once jaunty and circumspect, like thieves newly loosed in that dark electric, like young thieves in a glowing orchard, loosely jacketed against the cold and ten thousand worlds for the choosing.

If, like Adam and Eve, they are in fact leaving a world of innocence, they discover soon enough the darkness of the world. Eventually they see a 13-year-old boy who has joined them executed—he has killed a man to retrieve his stolen horse—and they themselves are thrown into a grim prison where they almost die. Yet in spite of it all, Grady holds on to what gives his life meaning, which is his love of horses and his love of a young woman he meets. Here’s a passage on the first love:

That night he dreamt of horses in a field on a high plain where the spring rains had brought up the grass and the wildflowers out of the ground and the flowers ran all blue and yellow far as the eye could see and in the dream he was among the horses running and in the dream he himself could run with the horses and they coursed the young mares and fillies over the plain where their rich bay and their rich chestnut colors shone in the sun and the young colts ran with their dams and trampled down the flowers in a haze of pollen that hung in the sun like powdered gold and they ran he and the horses out along the high mesas where the ground resounded under their running hooves and they flowed and changed and ran and their manes and tails blew off of them like spume and there was nothing else at all in that high world and they moved all of them in a resonance that was like a music among them and they were none of them afraid neither horse nor colt nor mare and they ran in that resonance which is the world itself and which cannot be spoken but only praised.

Later, having lost the woman but retrieved his horse, he reflects on the tradeoffs he has made:

He remembered Alejandra and the sadness he’d first seen in the slope of her shoulders which he’d presumed to understand and of which he knew nothing and he felt a loneliness he’d not known since he was a child and he felt wholly alien to the world although he loved it still. He thought that in the beauty of the world were hid a secret. He thought the world’s heart beat at some terrible cost and that the world’s pain and its beauty moved in a relationship of diverging equity and that in this headlong deficit the blood of multitudes might ultimately be exacted for the vision of a single flower.

In Blood Meridian we see the blood of multitudes in excruciating detail. “The Kid” finds himself a member of the Glanton gang, a group of scalp hunters who have been given carte blanche to massacre Indians and then, having been unleashed, turn their violence on all they encounter. At the core of the group is Judge Holden, a seven-foot albino psychopath who takes on mythic proportions as the book progresses. Highly educated and highly skilled, he appears the very archetype of violence, one who is timeless and impossible to kill. As the judge sees it, war is at the foundation of life:

This is the nature of war, whose stake is at once the game and the authority and the justification. Seen so, war is the truest form of divination. It is the testing of one’s will and the will of another within that larger will which because it binds them is therefore forced to select. War is the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence.

Having recently immersed myself in William Faulkner, I see the Mississippi author’s influence on McCarthy. Just as Faulkner reveals America’s dark history with regard to African Americans, so McCarthy does so with native Americans and in the settlement of the west generally. Harold Bloom, who regards the author as a worthy successor to Herman Melville (especially Moby Dick) and sees Blood Meridian as “the ultimate Western, not to be surpassed,” says of Holden that he seems to “judge the entire earth,” one who holds sway “over all he encounters.”

McCarthy’s ability to look unblinkingly at human horror can have a cathartic effect, reports Will Carthcart, a reporter who has witnessed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine first hand. Cathcart was in Mariupol when the Russians attacked, was captured and then released, and then fled to Tbilisi, Georgia, where his pregnant wife awaited him. Cathcart writes,

Just before dawn, the Ukrainians seized a bridge that allowed us to escape. The drive out of Kherson still haunts me. So much of what I saw, heard, and smelled invoked a Cormac McCarthy novel. I had nothing else to compare it with. No one should.

Further on, quoting from McCarthy’s last novel The Passenger, Cathcart says that

Cormac McCarthy had provided me with a context, even a language, to internalize the things I saw and cannot unsee. Segments of human beings were stacked along the road between the smoking-bombed-out war machines.

“The world’s truth constitutes a vision so terrifying as to beggar the prophecies of the bleakest seer who ever walked it. Once you accept that then the idea that all of this will one day be ground to powder and blown into the void becomes not a prophecy but a promise.”

Kherson is now free. But it will never be free of what happened. “A calamity can be erased by no amount of good. It can only be erased by a worse calamity.”

At this point in the article Cathcart also quotes Judge Holden:

War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner.

Cathcart sums up some of the lessons he has taken from McCarthy:

If the proper authorities ever caught wind of the narcotic potency of such novels, all books would be banned, repackaged, and sold by prescription to inhabitants of wealthy countries.

Reading The Road, Suttree, and Outer Dark on those maddening plastic mattresses hovering above the bleached linoleum was a reminder that things could be worse. If McCarthy could stash poetic elevation and transformative prose in such awful worlds, I figured I could find it.

In college, I gleaned that Blood Meridian is a life guide for the futile brutality of Western civilization. Is there anything more distinctly American than MacGyvering your own gunpowder out of piss and bat shit to kill a bunch of Native Americans?

His son having been born soon after Cathcart escaped to Georgia, he also sees specific lessons to be learned from The Road. He quotes from an interchange between the dying father and the son, who are trying to survive in a post-apocalyptic wasteland:

When Ethan asks me, “What’s the bravest thing you ever did?”

I will cough and spit blood onto the road. “Getting up this morning,” I will say to the boy.

I will tell him “To carry the fire.” And when he says he doesn’t know where the fire is.

I will tell him, “Yes you do. It’s inside you. It always was there. I can see it.”

Dark though McCarthy seems, Cathcart sees him as an important reality check:

For 60 years, beginning with The Orchard Keeper, Cormac McCarthy has explored social decay and taboo with the radiant darkness of his poetic prose. It was up to us to find the light.

Even at his bleakest, he is holding back—leaving room for hope in the inconceivable tragedy. He provides us with the tools for us to fashion that hope or with the realization that we must let it fall into place like the ashes of a nuclear winter.

All of which leads Cathcart to a personal note of affirmation:

Once I wondered if it was insane to deliberately cause a new human. Now I wonder if it is insane not to.