Spiritual Sunday

The final six weeks of a semester are always nuts. At the end of tumultuous grading storms, I find myself, like Robinson Crusoe, washed up on the beach and barely alive. I am compensated, however, by reassuring evidence that literature continues to work its magic on my students.

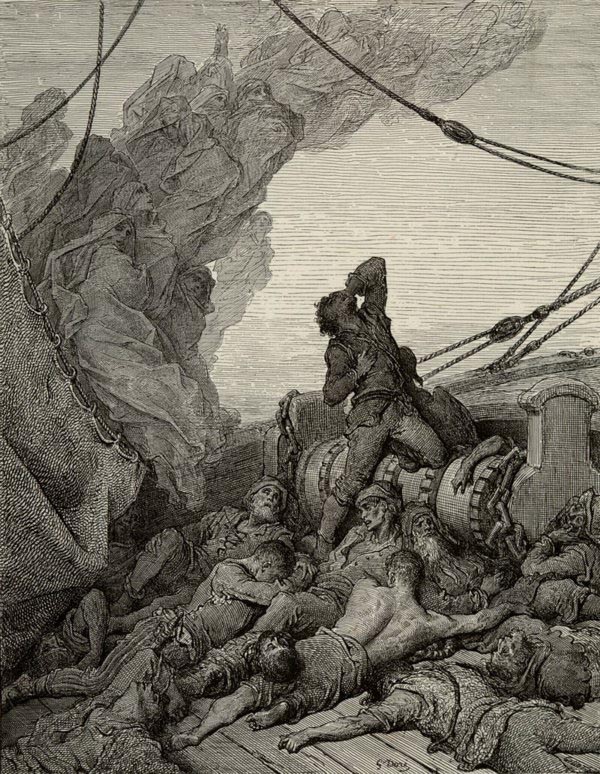

To continue this nautical theme, I share today an account of a Rime of the Ancient Mariner essay that I received from history major Peter Erdos in my Introduction to Literature class. (Peter gave me permission to use his name.) The poem, I learned, can have special meaning for someone with Crohn’s disease.

The essay wasn’t originally about the illness, however. Peter mentioned it in passing in an early draft that was confused about its intent. Peter knew the poem had moved him deeply but he wasn’t sure why. In a revision conference, we came to realize that Peter had undergone his own version of the mariner’s journey.

Peter was 11 when he learned that he had Crohn’s disease. As his father is a Lutheran pastor, Peter looked for a religious explanation, and he concluded that either God didn’t care about him or that He was actively punishing him. As Peter entered his high school years, he became increasingly depressed and cynical to the point that his father finally confronted him.

Although Peter says that his father never talks about religion at home, he did this time, collaring his son and saying, “Pete I’m tired of this crap! You feel like God doesn’t love you? Well you’re thinking like an idiot, and I know you’re not an idiot.”

He then told Peter to start paying more attention to the Bible, especially to Paul’s epistles.

I’ll get to the outcome in a moment, but let’s first look at why the poem hit Peter as it did. Peter said the albatross made him think of the Holy Spirit, which Matthew 3:16 compares to a dove. Peter’s own version of shooting the albatross was closing his heart to God. For a child who had been raised a Christian, this left Peter feeling terribly alone:

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

I’ll let Peter take it from here (I’ve edited his essay slightly):

By this point of the poem the Mariner is severely depressed about what he has done, and he wears the albatross as a constant reminder. Like Paul after God struck him blind for his persecution of Christians, the Mariner is feeling lost, but he cannot pull himself out of his self-pity. He feels alone and in a desolate place, which mirrors his spiritual desolation:

There passed a weary time. Each throat

Was parched, and glazed each eye.

A weary time! a weary time!

How glazed each weary eye…

He tries to make amends and apologize for what he has done, but, like me as a child, he has forgotten how to talk to God:

I looked to heaven, and tried to pray;

But or ever a prayer had gusht,

A wicked whisper came, and made

My heart as dry as dust.

The mariner’s epiphany comes, Peter says, when he blesses the water snakes, which formerly he has regarded as loathsome. Here’s Peter again:

The Mariner has finally reached what he was meant to reach. He reaches a spiritual epiphany where even what may seem as lowly and slimy monsters are truly beautiful creations of God. He doesn’t even know it when he blesses them. He has found the love that was always there for him. The weight of the Albatross finally leaves him.

When I found God again I finally stopped caring that I was perpetually sick. It did not matter to me. I finally felt as free as the Mariner when the weight of the Albatross leaves him:

The self-same moment I could pray;

And from my neck so free

The albatross fell off and sank

Like lead into the sea.

Peter particularly thrills to the passage where the mariner returns home—or, as Peter sees it, returns to God:

We drifted o’er the harbor-bar,

And I with sobs did pray—

O let me be awake, my God!

Or let me sleep alway.

As we talked about Peter’s evolution, he said that his father had essentially “fixed him with his glittering eye,” causing him, like the wedding guest, to become “a sober and a wiser man.” That explains Peter’s conclusion, where he looks towards his future. It’s not enough that he himself was reconciled to God. He now has the responsibility to help others. Here’s Peter concluding his essay (again, lightly edited):

It would be easy to assume that the Mariner’s story ends on the boat. That he has had an intense emotional epiphany and that is it. But he doesn’t feel that this is enough. Like me, the Mariner feels the need to go and teach others the path that has led him to this place of spiritual fulfillment. He, like the apostles Peter and Paul, must teach the lessons that he has been taught so that others who are in similar positions can avoid making the same mistakes—so that they don’t have to undergo the pain of long years of doubt and suffering.

St. Paul writes, “When I became a man I put away childish things.” I went through a phase of life where I was like the Mariner. Early on, I thought nothing could hurt me. I was self-confident, and after a point I forgot about God. When I got sick and scared, I needed something to believe in but I had forgotten how to pray. I became depressed and eventually thought, like the Mariner, that I was being punished for something that I had done. After a period where I didn’t believe that God cared about me and that I was suffering with a chronic illness for the rest of my life for no reason, I realized that God did this to mature me and to help me grow. I learned, through the Mariner’s penance, that God is teaching him about the sacredness of his creation in nature.

God has not forgotten the Mariner, and I know now that he has not forgotten me. God spoke to both of us through an intense spiritual epiphany that we both needed in order to feel like we had a purpose—like we both had a future.

Peter had already done a lot of spiritual wrestling before he came to Coleridge’s poem. Rime of the Ancient Mariner, however, has provided him with images and a narrative with which to further explore his life’s path.