Tuesday

There’s been a lot of discussion recently about a rise in death rates amongst white middle class Americans. The report by the most recent Nobel-winning economist is airing at the same time as the rich continue to get richer while middle class stagnate, middle class wages continue to stagnate, and angry voters rebel against the GOP establishment by applauding Donald Trump and Ben Carson. Pundits like Paul Krugman and Ross Douthat, both of The New York Times, are trying to connect the dots.

Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (1949) would help them come to an understanding.

Let’s first look at the report. According to economist Angus Deaton and his co-author Anne Case, mortality rates for middle-aged white Americans has been rising since 1999, even as death rates are declining in other countries and, even more significantly, in other American groups. Krugman lays out the findings:

Americans are, in increasing numbers, killing themselves, directly or indirectly. Suicide is way up, and so are deaths from drug poisoning and the chronic liver disease that excessive drinking can cause. We’ve seen this kind of thing in other times and places – for example, in the plunging life expectancy that afflicted Russia after the fall of Communism. But it’s a shock to see it, even in an attenuated form, in America.

Yet the Deaton-Case findings fit into a well-established pattern. There have been a number of studies showing that life expectancy for less-educated whites is falling across much of the nation. Rising suicides and overuse of opioids are known problems. And while popular culture may focus more on meth than on prescription painkillers or good old alcohol, it’s not really news that there’s a drug problem in the heartland.

To their credit, neither the liberal Krugman nor the conservative Douthat come up with partisan answers. Krugman does not blame the development only on wage stagnation and holes in the safety net and Douthat does not blame it only on cultural factors like a more permissive society or the decline of religion and the family.

Krugman even points to a cultural explanation offered up by Deaton himself:

So what is going on? In a recent interview Mr. Deaton suggested that middle-aged whites have “lost the narrative of their lives.” That is, their economic setbacks have hit hard because they expected better. Or to put it a bit differently, we’re looking at people who were raised to believe in the American Dream, and are coping badly with its failure to come true.

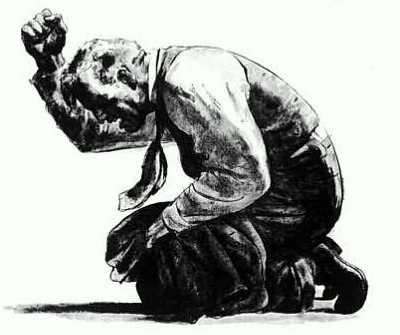

Cue Death of a Salesman, in which a salesman who can no longer handle his job commits suicide. Miller’s subject is the death of the American dream, a theme that has been with us practically since the founding of the republic. I sometimes think that American history is just an eternal careening between hope and disillusion.

Anyway, Death of a Salesman is all about people who are experiencing an existential crisis over what it means to be American. The more sensitive characters, like Biff, wander aimlessly, always feeling guilty that they’re not fulfilling their promise. The less sensitive ones, like Happy, hide their dissatisfaction from themselves and indulge in shallow gratifications and bullshit conversations. Willy Loman is one of the sensitive ones.

The tension is made clear by Willy’s incredulous response to Linda’s observation about their son:

Linda: I think he’s still lost, Willy. I think he’s very lost.

Willy: Biff Loman is lost. In the greatest country in the world a young man with such — personal attractiveness, gets lost. And such a hard worker.

As we learn about Willy’s past, he comes to seem more and more pathetic. Glorifying in Biff’s football prowess, he makes fun of his neighbor’s geeky kid, who will go on to achieve the success that Biff never does. Willy, meanwhile, engages in a sordid affair, grovels before his employer, and begins to blank out while driving. Finally he deliberately drives his car into a tree, attempting to make his death look like an accident so that he can defraud the insurance company.

Yet what Biff sees as a wasted life, their neighbor sees a man who is redeemed by his faith in the American dream. It’s up to the audience about whom to believe:

Linda: He was so wonderful with his hands.

Biff: He had the wrong dreams. All, all, wrong.

Happy (almost ready to fight Biff): Don’t say that!

Biff: He never knew who he was.

Charley: (stopping Happy’s movement and reply. To Biff): Nobody dast blame this man. You don’t understand: Willy was a salesman. And for a salesman, there is no rock bottom to the life. He don’t put a bolt to a nut, he don’t tell you the law or give you medicine. He’s man way out there in the blue, riding on a smile and a Shoeshine. And when they start not smiling back — that’s an earthquake. And then you get yourself a couple of spots on your hat, and you’re finished. Nobody dast blame this man. A salesman is got to dream, boy. It comes with the territory.

Biff: Charley, the man didn’t know who he was.

There’s no sign that the Lomans are intolerant nativists but I can imagine Willy today listening to Rush Limbaugh and Mark Levin as he drives around New England. Would he find, in political scapegoats, an explanation for his frustrations?

That would certainly provide him with a narrative, even though (as we are seeing) that narrative won’t necessarily keep him alive. One may, for instance, have a story about why Barack Obama is not a legitimate president, but such a belief won’t necessarily keep one away from alcohol or drugs.

Nancy Tourneau of The Washington Monthly comments on one interesting contrast in the recent reports. While white mortality may be up, Blacks and Hispanics are living longer, even though many are undergoing similar hardships. She quotes one Tim Wise for an explanation:

Invariably, it seems it is we in the white community who obsess over our own efficacy, and fail to recognize the value of commitment, irrespective of outcome. People of color, on the other hand, never having been burdened with the illusion that the world was their oyster, and thus, anything they touched could and should turn to gold, usually take a more reserved, and I would say healthier view of the world and the prospects for change. They know (as indeed they must) that the thing being fought for, at least if it’s worth having, will require more than a part-time effort, and will not likely come in the lifetimes of those presently fighting for it.

To which Tourneau adds,

None of that is meant to disparage white people or suggest that people of color are all heroes. It simply means that we have different stories of America that influence what we’ve come to expect. If, instead of fearing the changes that are taking place in our country, we could look to each other as sources of strength and wisdom, we might be able work together to challenge the forces that affect us all.

Willie Loman doesn’t have access to these communally supportive stories, however. In his world, you pull yourself up by your own bootstraps and, if you fail, the blame is all on you. The shame of failure leads up to take his anger out on himself and on his wife and kids.

We have a lot of Willy Lomans in America today.