Wednesday

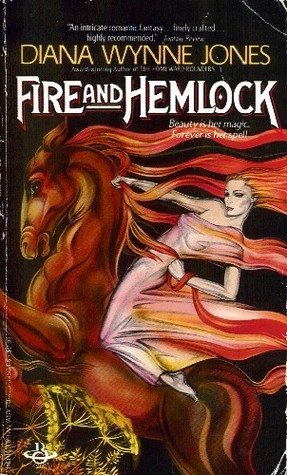

This past semester, for the first time, I taught Diana Wynne Jones’s Fire and Hemlock (1985) in my British Fantasy class. I have fallen in love with the book and a number of my students (but not all of them) have as well. I have taught mostly male fantasy in the past so this is an important addition.

In an essay appended at the end of the book entitled “The Heroic Ideal: A Personal Odyssey,” Jones herself talks about her frustrations with there not being female heroes in the fantasy she grew up with. While much fantasy literature demotes women to minor figures, she did find an exception in the Scottish ballad of Tam Lin, which provides a structure for Fire and Hemlock. My student Sophie Kessler, a math major, wrote a fine essay exploring how the old Scottish ballad helps the author break free from those narratives that confine women to a passive role.

You can go here to read the version of Tam Lin that Jones references but here’s a quick summary. Janet is forbidden to visit Carterhaugh because Tam Lin is there and those maids who encounter him do not return as maids. Nevertheless, Janet goes (of course) and meets Tam Lin. Sure enough, he gets her pregnant:

He’s ta’en her by the milk-white hand,

And by the grass-green sleeve,

He’s led her to the fairy ground

At her he askd nae leave.

At this point, however, the story takes an interesting twist. Instead of experiencing shame when she returns home, Janet instead stands up to her detractors. She does, however, appear to listen to her brother when he recommends an herbal abortifacient. When she goes in search of it, however, Tam Lin intervenes:

‘How dar’ ye pu’ a leaf he says,

‘How dar’ ye break the tree,

How dar’ ye scathe [harm] my babe,’ he says,

That’s between you and me?’

He then reveals that he would marry her only he’s currently a captive of the queen of the fairies. At the end of seven years, she will send him to hell:

And pleasant is the fairy land

For those that in it dwell,

But ay at end of seven years

They pay a teind [tax] to hell;

I am sae fair and fu’ o’ flesh

I’m fear’d ’twill be mysell.

If she follows a set of instructions, however, she can save him. This includes locating him on Halloween when the fairies gather and holding him tight, even as the fairies put him through a Protean series of transformations. Janet manages to hang on, to the fairy queen’s great disappointment:

Out then spak’ the Queen o’ Fairies,

And an angry woman was she,

She’s ta’en awa’ the bonniest knight

In a’ my companie!

At this point we assume that Tam Lin and Janet return home, marry, and live happily ever after.

In the novel, Polly is a college student who seems on track to marry a lawyer who doesn’t particularly excite her. In a return to her childhood home, however, she starts recalling forgotten events from when she was 11. On the one hand, she recalls the break-up of her needy mother and her irresponsible father. She also remembers magical encounters with Tom Lynn, a man in his twenties.

Tom and Polly’s interactions echo the ballad. They determine to be heroes together, and he gives her childhood fantasy classics, which are designed to function as instructional manuals. (They include Wizard of Oz, Nesbit’s Five Children and It and The Treasure Seekers, The Wolves of Willoughby Chase, Box of Delights, The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, and The Sword and the Stone.) She meanwhile gives him the confidence to break free of his ex-wife, who proves to be the queen of the fairies.

The books of fantasy are necessary if she is to escape the conventional romance narrative, to which adolescents are prone. When Polly develops a crush for Tom and fantasizes nursing him back to health after he is wounded, he calls her out for sentimental rubbish.

I won’t go into all the ins and outs of their relationship. I’ll only note that he, an older man, unhealthily relies on a young girl to save him. (Unlike the ballad, however, he does not get her pregnant, nor does he do anything sexually inappropriate.) She, meanwhile, is in danger of becoming like her mother, who is needy and so dependent on men that she drives them away.

Polly must escape her mother’s pattern if she is to find happiness, which is why Jones changes the end of the ballad. Holding Tom as Janet holds Tam Lin (and as Polly’s mother holds her men) is to lose him. Here are Tam Lin’s instruction to Janet in the ballad:

They’ll turn me in your arms, ladye,

An aske but and a snake;

But hauld me fast, let me na gae,

To be your warldis make.

‘They’ll turn me in your arms, ladye,

But and a deer so wild ;

But hauld me fast, let me na gae,

The father o’ your child.

They’ll shape me in your arms, ladye,

A hot iron at the fire ;

But hauld me fast, let me na go,

To be your heart’s desire.

‘They’ll shape me last in your arms, Janet,

A mother-naked man;

Cast your green mantle over me,

And sae will I be won.’

By contrast, Polly realizes that she must reject Tom. Only in doing so can she break the unhealthy dependency that they have upon each other. (In the process, she also realizes that she must break up with her fiancé.) The book hints but does not ascertain that there will be a later relationship between Polly and Tom. If there is, it will be healthier than the one that was developing.

My students and I talked about how fantasy can both entrap and liberate. On the one hand, Polly risks becoming trapped, like her mother, by conventional fairy tales that promise the arrival of a prince to save the damsel in distress. Fire and Hemlock, therefore, turns to a more egalitarian folk tale for an alternative narrative, although even this one Jones must rewrite to serve her purposes.

We also discussed how fantasy helps us process traumatic childhood events in a safe way. It is significant that fantasy in this case allows Polly to explore a dysfunctional upbringing that she has repressed but that is steering her life towards an unhappy marriage. Fantasy, in other words, allows us to go places we dread to visit.

In doing so, it gives us the tools to save ourselves.