Several weeks ago I knew nothing about Charles Dickens’ Little Dorrit. Now I think it’s an amazing novel and also a timely one. As I watched the President in his State of the Union speech Tuesday night describe how we are finally putting the 2008 recession behind us, I felt like protagonist Arthur Clennam at the end of the novel when he emerges from debtors prison and begins working productively again.

Clennam, like many others, is taken down by Mr. Merdle, a Bernie Madoff figure who is running a Ponzi scheme. Merdle works closely with the Barnacles, well-paid civil servants who work for “the Circumlocution Office.” As a result, Merdle establishes a reputation for guaranteed returns. Many innocent people are pulled in.

When he realizes the fraud will be discovered, Merdle, unlike Madoff, commits suicide. According to Dickens scholar Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, the affair was based on a bank crash that occurred in 1856 when Dickens was writing his novel. John Sadlier, a Member of Parliament and Junior Lord of the Treasury who was regarded as a financial wizard, was “busy plundering the Tipperary Bank until it …collapsed, with debts of £400,000.” He also committed suicide, and the bank owner he worked with was sentenced to 14 years for fraud.

Merdle’s association with the Barnacles is a good depiction of our own financial wizardry, where Wall Street financiers get special tax favors and banking deregulation from the government while creating paper rather than genuine wealth. In Dickens, the Circumlocution Office represents the way the people use government monies for the benefit of themselves and their friends while stiffing the public. Our own “Circumlocution Office” results in (to quote from Obama’s speech)“giveaways the superrich don’t need” and “lobbyists [who] have rigged the tax code with loopholes that let some corporations pay nothing while others pay full freight.”

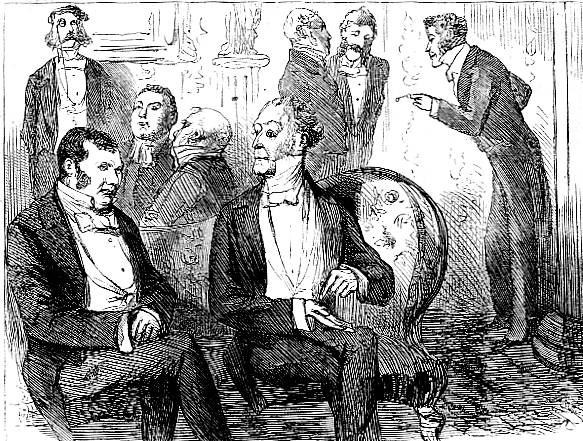

In Little Dorrit, there is a momentous meeting between Lord Tite Barnacle and Merdle that captures such unholy alliances:

As a vast fire will fill the air to a great distance with its roar, so the sacred flame which the mighty Barnacles had fanned caused the air to resound more and more with the name of Merdle. It was deposited on every lip, and carried into every ear. There never was, there never had been, there never again should be, such a man as Mr Merdle. Nobody, as aforesaid, knew what he had done; but everybody knew him to be the greatest that had appeared.

Dickens also compares the buying of Merdle shares to an epidemic, and it overtakes even the level-headed Pancks, a rent collector with a good heart. Just as respectable people were drawn into the Madoff scheme by other respectable people, so does Pancks draw in Clennam:

‘I’ve gone into it. I’ve made the calculations. I’ve worked it. [The investments are] safe and genuine.’ Relieved by having got to this, Mr Pancks took as long a pull as his lungs would permit at his Eastern pipe, and looked sagaciously and steadily at Clennam while inhaling and exhaling too.

In those moments, Mr Pancks began to give out the dangerous infection with which he was laden. It is the manner of communicating these diseases; it is the subtle way in which they go about.

‘Do you mean, my good Pancks,’ asked Clennam emphatically, ‘that you would put that thousand pounds of yours, let us say, for instance, out at this kind of interest?’

‘Certainly,’ said Pancks. ‘Already done it, sir.’

Mr Pancks took another long inhalation, another long exhalation, another long sagacious look at Clennam.

‘I tell you, Mr Clennam, I’ve gone into it,’ said Pancks. ‘He’s a man of immense resources—enormous capital—government influence. They’re the best schemes afloat. They’re safe. They’re certain.’

Of course the schemes are not certain at all, and both Pancks and Clennam are ruined when Merdle is exposed. By the end of the book, however—this is what reminded me of our country’s recovery—Clennam is out of prison and working with an engineer who knows how to build things that people actually need.

Think of him as someone serving his country by repairing our fraying infrastructure instead of being a Barnacle receiving special governmental favors for his own private indulgence.

The engineer’s words to Clennam could also apply to us as we recover from the nightmare of 2008:

First, not a word more from you about the past. There was an error in your calculations. I know what that is. It affects the whole machine, and failure is the consequence. You will profit by the failure, and will avoid it another time. I have done a similar thing myself, in construction, often. Every failure teaches a man something, if he will learn; and you are too sensible a man not to learn from this failure.

Let us pray that we have in fact learned and are not drawn into another bubble. Step #1 is to maintain and strengthen the regulatory mechanisms that we have set up to monitor the Merdles and the Barnacles.