Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. I’ll subscribe you via Mailchimp for the weekly or email you directly for the daily (your choice). Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone.

Thursday

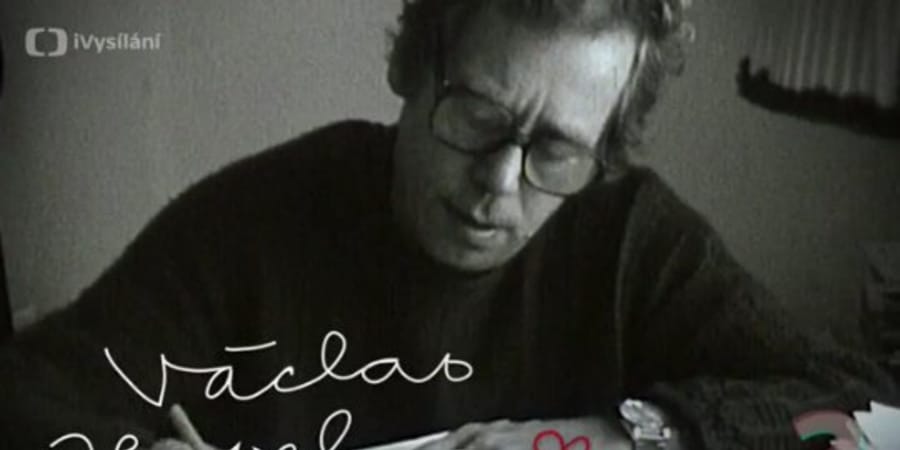

Former diplomat and Tolstoy enthusiast Fletcher Burton has just alerted me to the death of his State Department associate William H. Luers. As ambassador to Czechoslovakia in the early 1980s, Luers was instrumental in America’s support for playwright, dissident, and eventual president Václav Havel. According to Burton, Luers had the brilliant insight to recognize the historical significance of Havel as a writer-statesman.

Like many dissident writers in the Iron Curtain countries, Havel specialized in Theater of the Absurd, which captured the craziness and darkness of life under Soviet rule. I’ve noted recently that the Czech author Franz Kafka—the patron saint of absurdism—captures the way that Trump’s thugs have been disappearing people off the streets, and Havel very much followed in his countryman’s tradition. Absurdist theater is a particularly effective means of expressing dissent because it is allegorical: although it doesn’t directly point at the authoritarian regime (which can lead to prison), audience members learn to read its hidden messages.

Absurdism is also a way of laughing to keep from crying. As Havel said at one point ,

The only thing I can recommend at this stage is a sense of humor, an ability to see things in their ridiculous and absurd dimensions, to laugh at others and at ourselves, a sense of irony regarding everything that calls out for parody in this world. In other words, I can only recommend perspective and distance.

To be sure, not directly mentioning the repressive government didn’t aways protect dissident authors, and Havel himself spent some four years in prison.

Burton notes that Luers had the savvy to enroll many of America’s leading writers in support of Havel, thereby helping form a protective screen around him and ultimately playing a small role in the relatively smooth and bloodless Velvet Revolution of 1989. These authors included John Updike, Edward Albee, E.L. Doctorow, Kurt Vonnegut, Allen Ginsberg, and Philip Roth. Although petitions from authors have a mixed history when it comes to impacting history, in this case authors contributed to Havel’s stature, which in turn made him more politically effective.

We really could use a Havel today in America. Among his pronouncements were the following:

— I feel that the dormant goodwill in people needs to be stirred. People need to hear that it makes sense to behave decently or to help others, to place common interests above their own, to respect the elementary rules of human coexistence.

–You do not become a ”dissident” just because you decide one day to take up this most unusual career. You are thrown into it by your personal sense of responsibility, combined with a complex set of external circumstances. You are cast out of the existing structures and placed in a position of conflict with them. It begins as an attempt to do your work well and ends with being branded an enemy of society.

–Ideology is a specious way of relating to the world. It offers human beings the illusion of an identity, of dignity, and of morality while making it easier for them to part with them.

–Even a purely moral act that has no hope of any immediate and visible political effect can gradually and indirectly, over time, gain in political significance.

–If the main pillar of the system is living a lie, then it is not surprising that the fundamental threat to it is living the truth. This is why it must be suppressed more severely than anything else.

–Vision is not enough, it must be combined with venture. It is not enough to stare up the steps, we must step up the stairs.

There’s also his pronouncement about hope:

The kind of hope I often think about (especially in situations that are particularly hopeless, such as prison) I understand above all as a state of mind, not a state of the world. Either we have hope within us or we don’t; it’s a dimension of the soul; it’s not essentially dependent on some particular observation of the world or estimate of the situation. Hope is not prognostication. It is an orientation of the spirit, an orientation of the heart; it transcends the world that is immediately experienced, and is anchored somewhere beyond its horizons. Hope, in this deep and powerful sense, is not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously headed for early success, but, rather, an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed..

Burton told me that he had a chance to meet Luers this past February. Here’s his account of what happened:

I greeted him, “Good morning, Ambassador. You are a diplomatic legend.” This put a smile on his face.

As we parted, I asked him to name the highlight of his career.

His one-word answer: “Havel!”

Once our State Department had figures such Huers and Burton. If, despite all its faults, America has accomplished much good in the world since 1945, it is largely because of the work of its diplomats. Now, as in so many other areas, Trump and his enablers are in the process of driving such people out.