Thursday

Novelist Zadie Smith has a wonderfully nuanced essay in the recent New York Review of Books in which she grapples with the issue of cultural appropriation. The question is whether writers can cross gender, class, race, ethnic and other lines in their fiction, appropriating the Other for their own stories. Is it okay for white writers to create black characters, straight writers to creates LBGTQ characters, and so on? Are these acts of cultural appropriation?

Smith’s answer to these questions is essentially yes and no. It’s okay if the writer produces authentic figures but not if the writer creates caricatures. Whether a figure is authentic or not, however, she leaves up to the reader to decide. And she acknowledges that readers often disagree.

Less controversially than writers, readers cross these boundary lines all the time. Smith herself remembers being moved by a white Victorian woman, a 20th century African American woman, a 20th century Trinidadian man, and a white Victorian man when she was growing up:

I lived in [books] and felt them live in me. I felt I was Jane Eyre and Celie and Mr. Biswas and David Copperfield. Our autobiographical coordinates rarely matched. I’d never had a friend die of consumption or been raped by my father or lived in Trinidad or the Deep South or the nineteenth century. But I’d been sad and lost, sometimes desperate, often confused. It was on the basis of such flimsy emotional clues that I found myself feeling with these imaginary strangers: feeling with them, for them, alongside them and through them, extrapolating from my own emotions, which, though strikingly minor when compared to the high dramas of fiction, still bore some relation to them, as all human feelings do. The voices of characters joined the ranks of all the other voices inside me, serving to make the idea of my “own voice” indistinct. Or maybe it’s better to say: I’ve never believed myself to have a voice entirely separate from the many voices I hear, read, and internalize every day.

In this spirit, Smith quotes Walt Whitman’s

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

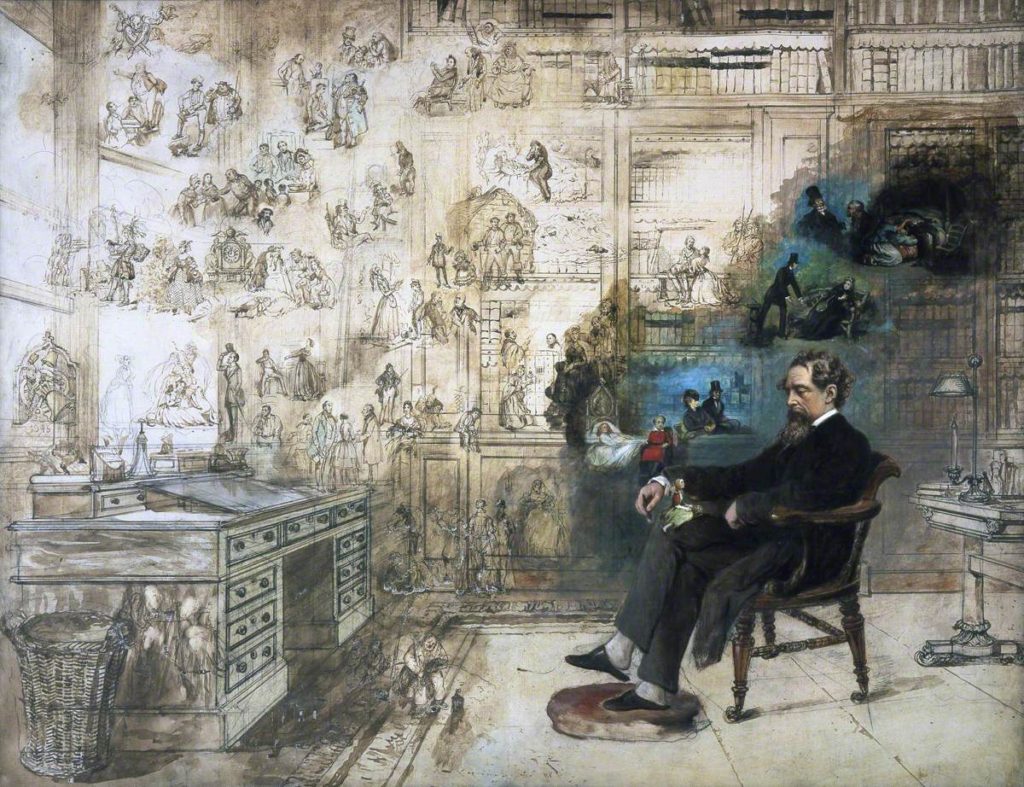

She also talks about the famous picture (see below) of Dickens’s imaginary multitudes.

Smith’s essay is a genuine dialogue, however, and she admits the arguments on the other side. Whitman’s containment has disturbing aspects:

[A] counter-voice in my head detects, in Whitman’s lines, not a little entitlement. Containing multitudes sounds, just now, like an act of colonization. Who is this Whitman, and who does he think he is, containing anyone? Let Whitman speak for Whitman—I’ll speak for myself, thank you very much. How can Whitman—white, gay, American—possibly contain, say, a black polysexual British girl or a nonbinary Palestinian or a Republican Baptist from Atlanta? How can Whitman, dead in 1892, contain, or even know anything at all of the particularities of any of us, alive as we are, in this tumultuous year, 2019?

In the course of her essay, Smith provides a number of instances of containment, including John Updike’s caricatures of black men (“precisely evidence of grotesque containment”) and Margaret Mitchell’s of black women:

[W]hen Margaret Mitchell published Gone With the Wind, there were a vanishingly small number of nontoxic representations of black women in the culture, and therefore the damage Mitchell did with her notorious “Mammy” character was substantial: she placed a fresh dose of an old poison into the culture that still exists and reached even me, aged twelve, in my little corner of London, looking for some form of cultural reflection, any kind at all, but finding only distorted mirrors, monstrous cliché, debasing ridicule, false containment.

One way of counteracting caricatures is for people of color to “write what they know.” Smith points out,

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, writing by women, and by oppressed minorities of all kinds, has wondrously expanded the literary landscape, ennobling griefs that had, historically, either passed unnoticed or been brutally suppressed and caricatured.

But that too is not the end of the argument since we don’t want to anyone, oppressed or not, to write only about people like them. For one thing, Smith notes that fiction uncovers dimensions of ourselves that we are unaware of. We are more than our demographic identities.

Furthermore, from the beginning, fiction has been interested in opening up windows into people unlike ourselves. For instance, Daniel Defoe’s fascination with figures like the thief Moll Flanders and the courtesan Roxana launched the English novel. Smith mentions her own novel about “an imaginary, multi-hyphenated British-Jewish-Chinese boy.”

At the heart of fiction is curiosity and compassion. About the first, Smith describes writers as “people with voices in our heads and a great deal of inappropriate curiosity about the lives of others.” For the second, she quotes Colombian writer Héctor Abad:

Compassion is largely a quality of the imagination: it consists of the ability to imagine what we would feel if we were suffering the same situation. It has always seemed to me that people without compassion lack a literary imagination—the capacity great novels give us for putting ourselves in another’s place—and are incapable of seeing that life has many twists and turns and that at any given moment we could find ourselves in someone else’s shoes: suffering pain, poverty, oppression, injustice or torture.

To the question of whether a novel is genuinely open to other voices or simply attempts to contain them, Smith says it’s often both:

The textbook example is Madame Bovary. For over a century, women have profoundly identified with this imaginary woman, created by a man, who himself supposedly claimed an outrageous personal identification with the other: Madame Bovary, c’est moi. I am one of those women readers, and yet there are many moments in Madame Bovary when I feel the presence of a masculine consciousness behind it all, as I do when I read Anna Karenina. Which is to say the mapping of self to other that Flaubert and Tolstoy attempted is not perfect. But it is not nothing. Anna Karenina has meant as much to me as any imaginary woman could.

By the end of her piece, Smith is saying that, even when novels get some parts of us wrong, they don’t necessarily get all of us wrong. Sometimes even insensitive novels seem to know us better than other humans do and even better than we ourselves do. It’s up to each of us to decide if a novel is opening us up or closing us down. Whether, as Wayne Booth frames it, the book is a good friend or a false friend. Here’s Smith:

I have closed novels and stared at their back covers for a long moment and felt known in a way I cannot honestly say I have felt known by many real-life interactions with human beings, or even by myself. For though the other may not know us perfectly or even well, the hard truth is we do not always know ourselves perfectly or well. Indeed, there are things to which subjectivity is blind and which only those on the outside can see. But, frustratingly, there are no fixed rules to regulate this process. We know some representations are privileged and some ignored. Prejudice in these matters must be thought through, each and every time. Is this novel before me an attempt at compassion or an act of containment? Each reader will decide. This is the work of an individual consciousness and cannot be delegated to generalized arguments…

Keep this in mind next time an author is excoriated for, as Smith puts it, stepping outside his or her lane. Authors may get things wrong but that’s different from saying that they shouldn’t make the attempt in the first place.