Wednesday

For the final assignment for my Theories of the Reader senior seminar class, my students select a literary work that, at some time in its history, functioned as “an event.” Their task is to describe the event and figure out its meaning. I spent Thanksgiving break reading the essays and have learned many remarkable things.

For instance, did you know that fundamentalist Christians targeted L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz in 1980s? They even won a lawsuit again the book.

According to my student Rebecca Kaff, parents were worried about their children being “seduced into godless supernaturalism.” The judge ruled in their favor, granting them compensation for the cost of transferring their kids to other schools and also allowing children to opt out of reading the book.

As Rebecca dug deeper into the book’s reception, however, she discovered there was more. The objections appear to have been directed mainly at the witches, especially the good witches (Glinda the Good and the Good Witch of the North). Witches were in the news at the time because feminists were reclaiming witch power, delving into history to rewrite the history of witchcraft and, in some cases, embracing the Wicca religion and resurrecting various earth goddesses. As has often been the case with witches, the Christian objections were to “godless superstition” per se but to the way that assertive women were challenging traditional patriarchy.

And wait, there’s more. Rebecca also discovered, from reading Evan Schwartz’s American History article “The Matriarch behind the Curtain,” that Baum’s good witches were in fact inspired by the women’s rights movement:

In 1882 Baum married Maud Gage, the daughter of Matilda Gage, “the most radical leader of the American woman’s rights movement.” Being a suffragist who worked with Anthony and Stanton, Gage was unwilling to let her daughter become a housewife and opposed the marriage as supported by Baum’s various bankruptcies and moves. Baum corresponded with her as she broke away from major suffragist movements to form the National Women’s Liberal Union and speak out about how women have been persecuted for centuries by men for witchcraft.

And:

Baum sympathized with Gage’s feelings and was influenced by her accounts of the witch hunts for his characters…[H]e began to see her as a “spiritual mentor” who would advise and inspire him. When she visited Baum in 1888, she bid him write down the stories he told to his children, many of which were later published as fairy tale collections…After she passed away in 1898, he began writing The Wizard of Oz …[and] used the novel to honor her through Glinda the witch, who sends Dorothy home–redeeming her just as Gage did him.

In other words, the Tennessee fundamentalists were picking up on some deep currents in the book.

Nor was it only fundamentalists who were threatened. Rebecca observes that the famous 1939 movie itself toned down some of the book’s feminism. Although Dorothy is older in the film than in the book, she is actually less capable. Film Dorothy is tied more to Aunt Em, she cries more, she describes herself as “small and meek,” and in the end she vows never to leave home again.

Dorothy displays far more gumption in the book. Rebecca writes,

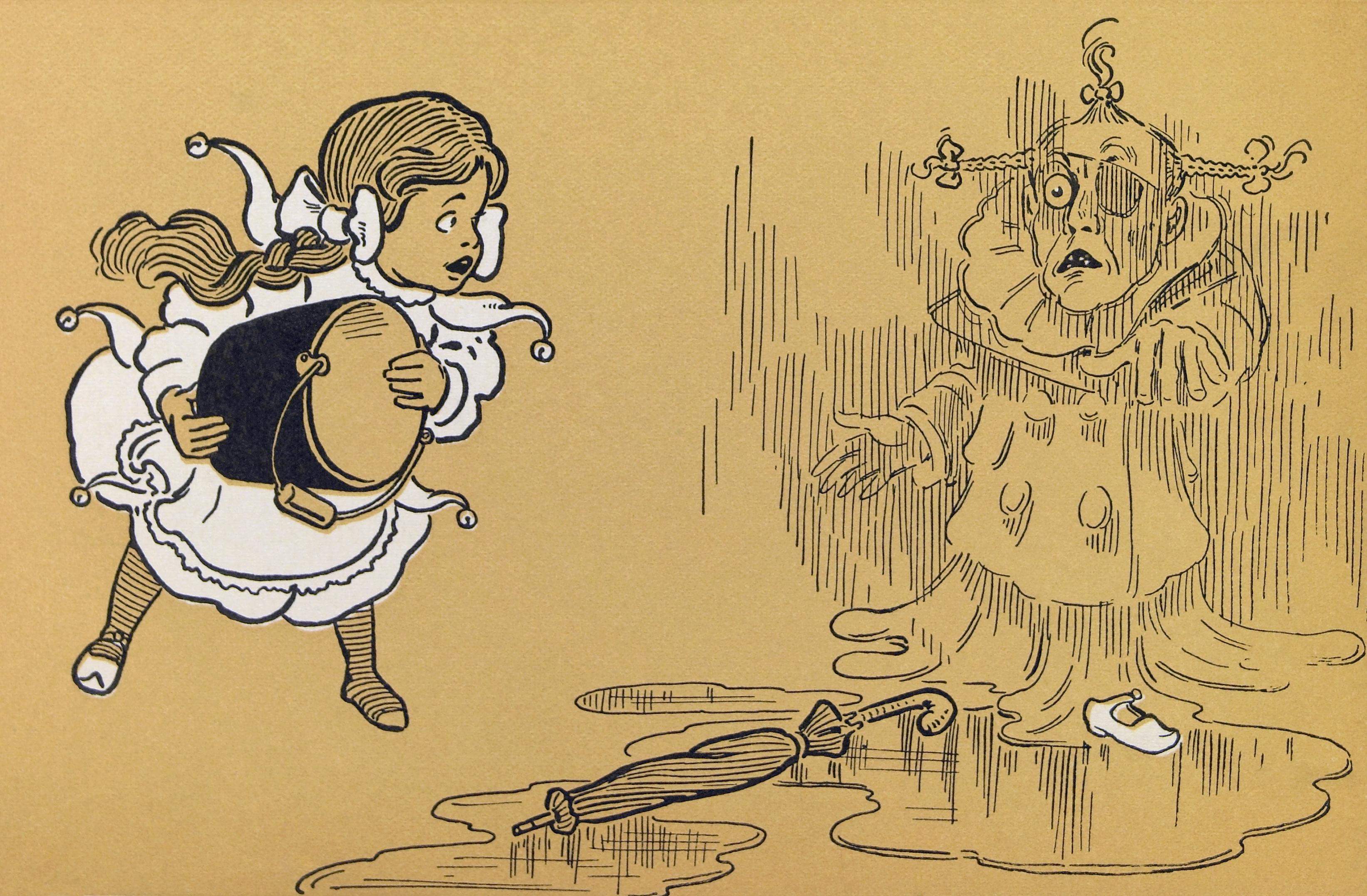

Multiple critics have praised the book’s version where Dorothy purposely dumps water on the witch in retaliation for the taking of her silver shoe. Then, not stopping to cry, “she drew another bucket of water and threw it over the mess. She then swept it all out the door.”

From the first, in other words, Dorothy is an assertive female heroine, emerging out of the women’s rights movement and probably harkening back as well to America’s pioneer women.

Never underestimate how much strong women freak people out.