Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Friday

The election of an adjudicated rapist, along with such gloating from Trumpists as “your body, my choice,” has certain American women turning to the ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata. Or at least they’re citing a South Korean movement that is following the strategy set forth in the play.

According to a Rachel Triesman NPR article, a South Korean movement known as 4B or the 4 No’s (bi means “not” in Korean) calls for the refusal of (1) dating men (biyeonae), (2) sexual relationships with men (bisekseu), (3) heterosexual marriage (bihon) and (4) childbirth (bichulsan). Triesman reports,

Interest in the 4B movement has surged in the days since the election, with Google searches spiking and the hashtag taking off on social media. Scores of young women are exploring and promoting the idea in posts on platforms like TikTok and X.

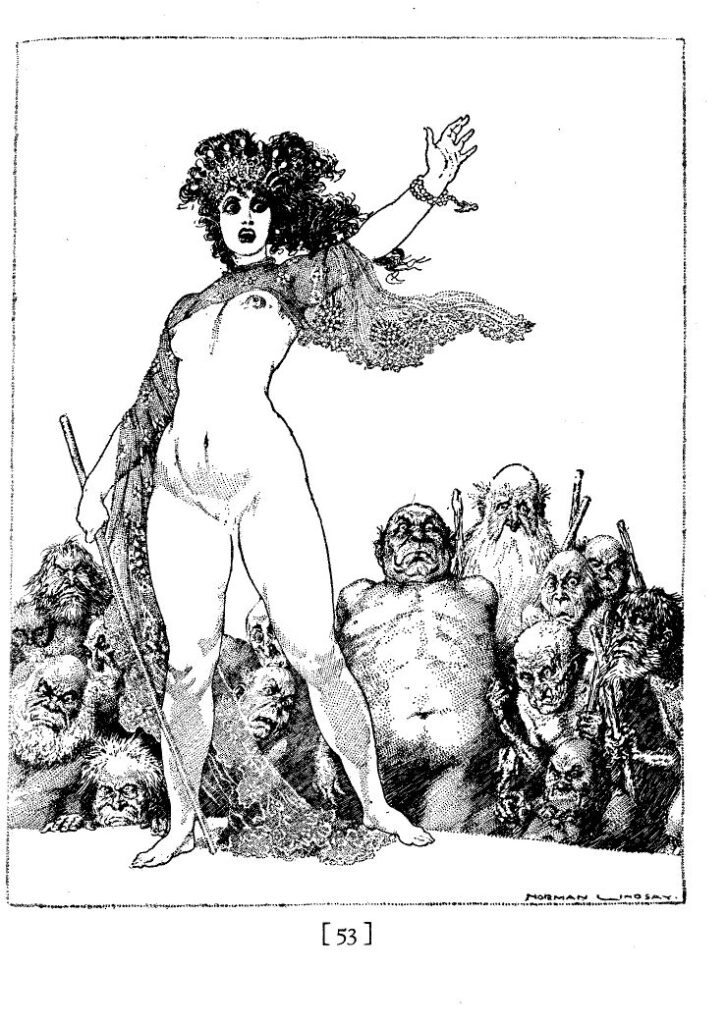

In Aristophanes’ 411 BCE comedy, the women of Greece launch a sex strike to bring an end to the years-long Peloponnesian War (431-404). We hear about female frustrations from Lysistrata, an Athenian woman who becomes the movement’s leader:

Lysistrata: All the long years when the hopeless war dragged along we, unassuming, forgotten in quiet,

Endured without question, endured in our loneliness all your incessant child’s antics and riot.

Our lips we kept tied, though aching with silence, though well all the while in our silence we knew

How wretchedly everything still was progressing by listening dumbly the day long to you.

For always at home you continued discussing the war and its politics loudly, and we

Sometimes would ask you, our hearts deep with sorrowing though we spoke lightly, though happy to see,

“What’s to be inscribed on the side of the Treaty-stone

What, dear, was said in the Assembly today?”

“Mind your own business,” he’d answer me growlingly, “hold your tongue, woman, or else go away.”

And so I would hold it.

Determined not to remain passive anymore, Lysistrata teams up with the Spartan Lampito to take action. It’s not easy, however, as women love sex just as much as men do. Lysistrata learns early on the challenges ahead:

Lysistrata: We must refrain from every depth of love….

Why do you turn your backs? Where are you going?

Why do you bite your lips and shake your heads?

Why are your faces blanched? Why do you weep?

Will you or won’t you, or what do you mean?

Myrrhine: No, I won’t do it. Let the war proceed…

Calonice: Anything else? O bid me walk in fire

But do not rob us of that darling joy.

What else is like it, dearest Lysistrata?

Lysistrata stands firm, however, and outlines strategies to make the strike more effective:

Lysistrata: By the two Goddesses, now can’t you see

All we have to do is idly sit indoors

With smooth roses powdered on our cheeks,

Our bodies burning naked through the folds

Of shining Amorgos’ silk, and meet the men

With our dear Venus-plats plucked trim and neat.

Their stirring love will rise up furiously,

They’ll beg our arms to open. That’s our time!

We’ll disregard their knocking, beat them off–

And they will soon be rabid for a Peace.

I’m sure of it.

The danger of forced sex—what we call marital rape—is mentioned, but Lysistrata has a plan for that as well:

Calonice: But if they should force us?

Lysistrata: Yield then, but with a sluggish, cold indifference.

There is no joy to them in sullen mating.

Besides we have other ways to madden them;

They cannot stand up long, and they’ve no delight

Unless we fit their aim with merry succour.

The women then all repeat the following oath after Lysistrata, which they follow up by sacrificing a bowl of wine:

Lysistrata: SO, grasp the brim, you, Lampito, and all.

You, Calonice, repeat for the rest

Each word I say. Then you must all take oath

And pledge your arms to the same stern conditions–

To husband or lover I’ll not open arms

Though love and denial may enlarge his charms.

But still at home, ignoring him, I’ll stay,

Beautiful, clad in saffron silks all day.

If then he seizes me by dint of force,

I’ll give him reason for a long remorse.

I’ll never lie and stare up at the ceiling,

Nor like a lion on all fours go kneeling.

If I keep faith, then bounteous cups be mine.

If not, to nauseous water change this wine.

Do you all swear to this?

Myrrhine: We do, we do.

Lysistrata: Then I shall immolate the victim thus. (drinks from the bowl)

For all their resolve, however, the women have difficulty denying their sexual cravings. Lysistrata must remain vigilant to keep them in line:

Lysistrata: What use is Zeus to our anatomy?

Here is the gaping calamity I meant:

I cannot shut their ravenous appetites

A moment more now. They are all deserting.

The first I caught was sidling through the postern

Close by the Cave of Pan: the next hoisting herself

With rope and pulley down: a third on the point

Of slipping past: while a fourth malcontent, seated

For instant flight to visit Orsilochus

On bird-back, I dragged off by the hair in time….

They are all snatching excuses to sneak home.

In the following interchange with a couple of these women, sexual innuendo involving female anatomy ranges wild and free:

1st woman: I must get home. I’ve some Milesian wool

Packed wasting away, and moths are pushing through it.

Lysistrata: Fine moths indeed, I know. Get back within.

1st woman: By the Goddesses, I’ll return instantly.

I only want to stretch it on my bed.

Lysistrata: You shall stretch nothing and go nowhere either.

1st woman: Must I never use my wool then?

Lysistrata: If needs be.

2nd woman: How unfortunate I am! O my poor flax!

It’s left at home unstript.

Lysistrata: So here’s another

That wishes to go home and strip her flax.

Inside again!

Eventually all the women sign on, however, and some even engage in effective guerilla tactics, such as teasing their husbands and then running away at the critical moment. The playwright conveys the resultant desperation of the men by having them carry long poles, which bulge conspicuously under their tunics. Soon they are having conversations such as the following, which once again feature non-stop innuendo:

Chorus: Here come the Spartan envoys with long, worried beards.

Hail, Spartans how do you fare?

Did anything new arise?

Spartans: No need for a clutter o’ words. Do ye see our condition?

Chorus: The situation swells to greater tension.

Something will explode soon.

Spartans: It’s awful truly.

But come, let us with the best speed we may

Scribble a Peace.

Chorus: I notice that our men

Like wrestlers poised for contest, hold their clothes

Out from their bellies. An athlete’s malady!

Since exercise alone can bring relief.

Athenians: Can anyone tell us where Lysistrata is?

There is no need to describe our men’s condition,

It shows up plainly enough.

Chorus: It’s the same disease.

Do you feel a jerking throbbing in the morning?

Athenians: By Zeus, yes! In these straits, I’m racked all through.

Unless Peace is soon declared, we shall be driven

In the void of women to try Cleisthenes.

In the end, it is clear to all that everyone should be making love, not war. Those of our own citizens who fantasize about dominant men and submissive women would benefit from this vision where everyone gets what he or she wants. At the end of the play, joy reigns supreme:

Lysistrata: In the end, Earth is delighted now, peace is the voice of earth.

Spartans, sort out your wives: Athenians, yours.

Let each catch hands with his wife and dance his joy,

Dance out his thanks, be grateful in music,

And promise reformation with his heels.

Athenians: O Dancers, forward. Lead out the Graces,

Call Artemis out;

Then her brother, the Dancer of Skies,

That gracious Apollo.

Invoke with a shout

Dionysus out of whose eyes

Breaks fire on the maenads that follow;

And Zeus with his flares of quick lightning, and call,

Happy Hera, Queen of all,

And all the Daimons summon hither to be

Witnesses of our revelry

And of the noble Peace we have made,

Aphrodite our aid.

Although tragedy lays claim to more literary glory than comedy, the latter, with its emphasis on sex and the body, articulates a powerful life force that will not be denied. To be sure, Lysistrata did not bring an end to Athens-Sparta hostilities, and I’m skeptical of the long-term effectiveness of the 4B movement. But such comic drama, by providing the powerless with a voice, can bolster their spirits and keep them going in the face of oppression. Throughout human history, comedy has always played this vital social role.