Monday

Although we’re not hearing much about climate change in this year’s election, global warming is not going away. Last week Phoenix extended its record-setting pace of consecutive days over 100ºF (37.78ºC), with the 100th day clocking in at 111ºF (43.89ºC). I am put in mind of Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land, where we see a group of people journeying out into space because earth has become uninhabitable.

Cloud Cuckoo Land is a novel within a novel, with Doerr having made up a work of fantasy by 2nd century Greek author Antonius Diogenes (who himself is real). Diogenes wrote a novel, The Wonders Beyond Thule, but it is has been lost to time. All we have is a synopsis of it by another writer.

The novel that Doerr imagines Diogenes to have written is a comic account of a man who wants to be transformed into a bird so that he can visit a bird utopia in the clouds—but who, through a series of mishaps, is instead transformed first into a much-abused ass and then into a hunted fish. We see the work survive the fall of Constantinople, make its way to Italy and the Vatican library, get performed by school children in 20th century Idaho, and then bolster a 22nd century girl, who is the sole survivor of a viral outbreak on the spaceship .

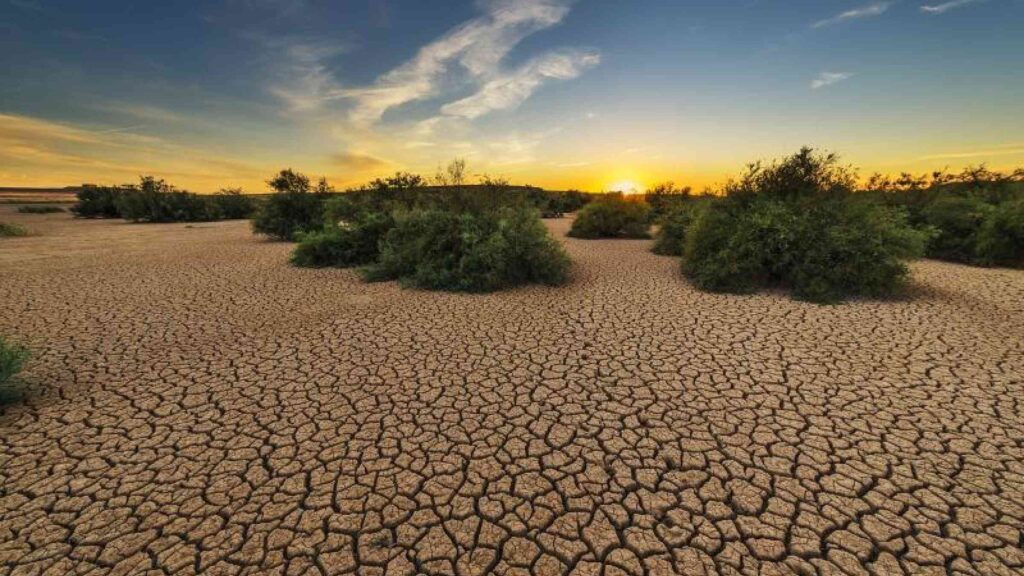

For his account of climate change’s impact, Doerr has drawn on Bill McKibben’s book Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? In the case of space traveler Konstance, prolonged drought has destroyed her father’s family farm. With nothing else to do as she barrels through space, she begins researching the Diogenes novel to figure out how it got into the hands of her father and through him to her. The ship’s computer, operating like an advanced Siri with access to all the world’s libraries, shows her images of the drought-stricken landscape that her father left behind:

The Earth flies toward her, inverts, the southern hemisphere pivoting as it rushes closer, and she drops from the sky onto a road line with eucalyptus. Bronze hills bake in the distance; white fencing runs down both sides. A trio of faded banners, strung overhead, reads,

DO YOUR PART

DEFEAT DAY ZERO

YOU CAN DO WITH 10 LITRES A DAY

As the computer takes her to the family homestead, she sees the damage that the drought has wrought: “Only one green year in the past thirteen.” The sight of the ravaged farm helps her better understand her father’s decision to leave:

Her father applied to join the crew when he was twelve, advanced through the application process for a year. At age thirteen—the same age Konstance is now—he would have received the call. Surely he understood that he would never live long enough to reach Beta Oph2? That he would spend the resto of his life inside a machine. Yet he left anyway.

It’s a fantasy to think that space travel will save us from ourselves, as Doerr’s book makes clear. It’s either this world or nothing. Or as Frost puts it, “Earth’s the right place for love, I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.”

I won’t spoil the novel by talking about what happens next. What I loved about Cloud Cuckoo Land is the way that a work of literature—and a comic one at that—can have a profound impact throughout the centuries. Doerr’s shows his novel within his novel providing solace to a little girl in the final days of Constantinople, helping her develop a relationship with an Ottoman ox-cart driver (who saves her from slavery), rejuvenating a lonely homosexual living in rural Idaho, keeping up the morale of Idaho school children when they are endangered by an eco-terrorist, and supporting an orphan in outer space.

As an added bonus, Cloud Cuckoo Land is yet another literary warning about the threat posed by climate change, joining such works as Margaret Atwood’s Oryk and Crake trilogy, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, and Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower.

Further thought: It so happens that as I was writing today’s post, reader Patty R sent me an article about Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia, in which appears a passage that applies to Doerr imagining what Diogenes might have written. Thomasina is heartbroken when she learns about all the books that were lost when the fabled library of Alexandria burned down but her tutor offers him some comfort:

Thomasina: Oh Septimus!—can you bear it? All the lost plays of the Athenians! Two hundred at least by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides—thousands of poems—Aristotle’s own library brought to Egypt by the noodle’s ancestors! How can we sleep for grief?”\

Septimus: By counting our stock. Seven plays from Aeschylus, seven from Sophocles, and nineteen from Euripedes, my lady! You should no more grieve for the rest than for a buckle lost from your first shoe, or for your lesson book which will be lost when you are old. We shed as we pick up, like travelers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those behind. The procession is very long and life is very short. We die on the march. But there is nothing outside the march so nothing can be lost to it. The missing plays of Sophocles will turn up piece by piece, or be written again in another language.