Wednesday

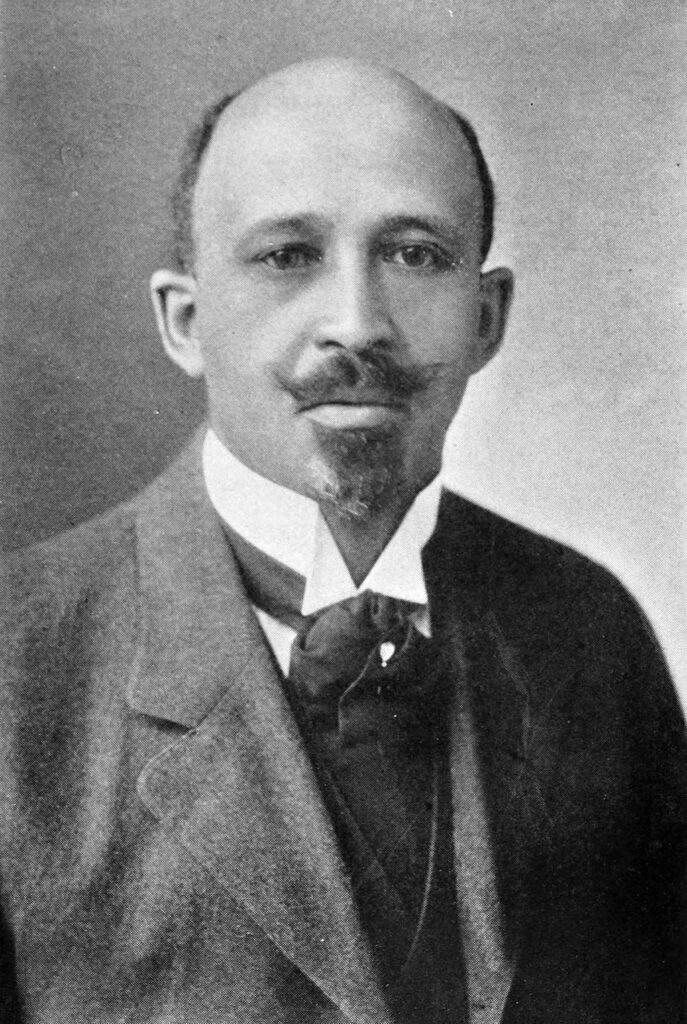

Thanks to my wonderful friend and editor Rebecca Adams, my book project is approaching its final stages as I bring the manuscript into line with her suggestions. In the revision process, I’ve also been taking advantage of some related articles she’s sent me, including a very useful piece by David Withun, headmaster of Jacksonville Classical Academy, who contrasts W.E.B. Du Bois’s views of literature with those of Booker T. Washington.

I have a chapter on Du Bois in my book, but most of it is devoted to his essay pointing out how, for much of history, white authors and audiences have been blind to their racial biases. As this viewpoint does not sit well with many conservatives, they might be surprised to discover that Du Bois was also a strong defender of a classical education. Thanks to Withun’s article, I will amend my chapter to include this fact.

Withun points out that Du Bois’s disagreements with Washington anticipate our current conflict between pre-professional and liberal arts educations. Washington, he notes, believed that African Americans

should learn useful trades that were relevant in post-Civil War America. By achieving success in the booming late 19th-century U.S. economy — mastering a practical trade in the fields of agriculture or mechanics, for instance — Washington believed black Americans could earn the respect of their white countrymen. He wanted the school he founded, the Tuskegee Institute, to educate black Americans to be self-sufficient contributors to the existing society.

Du Bois, on the other hand, worried that such education “would create a permanent caste system in the United States, restraining the potential of black Americans and creating a two-tiered society.” To break out of this, Du Bois believed, African Americans needed progressive legislation, the right to vote, and access to a liberal arts education. Apparently he had a “great books” list that he thought all Americans should read that included works by Lucretius, Livy, Cicero, Dante, and Cervantes.

His disagreements with Washington have been famously and succinctly captured in a Dudley Randall poem, especially the following stanzas:

“It seems to me,” said Booker T.,

“It shows a mighty lot of cheek

To study chemistry and Greek

When Mister Charlie needs a hand

To hoe the cotton on his land,

And when Miss Ann looks for a cook,

Why stick your nose inside a book?”

“I don’t agree,” said W.E.B.,

“If I should have the drive to seek

Knowledge of chemistry or Greek,

I’ll do it. Charles and Miss can look

Another place for hand or cook.

Some men rejoice in skill of hand,

And some in cultivating land,

But there are others who maintain

The right to cultivate the brain.”

“Chemistry and Greek” are shorthand for a well-rounded education. Du Bois reveled in the fact that he did not feel racially excluded when he turned to the classics:

I sit with Shakespeare, and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm and arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out of the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed Earth and the tracery of stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil.

Withum points out that, for Du Bois, “knowledge of the humanities and citizenship were fundamentally linked.” He saw the purpose of education as rising

above the “veil” culturally dividing the races so men could experience their shared intellectual history and have insight into each other’s lives. For him, the means to this education were the old, time-tested methods. Indeed, he and his colleagues provided such an education to the children of freedmen at Atlanta University.

And then there’s this juicy quote:

Nothing new, no-time saving devices — simply old time-glorified methods of delving for Truth, and searching out the hidden beauties of life, and learning the good living,” DuBois wrote. “The riddle of existence is the college curriculum that was laid before the Pharaohs, that was taught in the groves by Plato, that formed the trivium and quadrivium, and is today laid before the freedmen’s sons at Atlanta University.”

In a related item, Rebecca also sent me a video of two Black academics, Anika Prather and Angel Parham, whose forthcoming The Black Intellectual Tradition: Reading Freedom in Classical Literature is very much in the Du Bois spirit. Rather than dismiss classical lit as the product of dead white and western men, Prather and Parham discuss how African Americans saw themselves in many of the conversations about freedom, goodness, and truth. Black poets and thinkers took conversations initiated by Aristotle, Cicero, Augustine and others and applied them to their own situations—just as, in a similar act of appropriation, they used the Bible for their purposes

In other words, leftists shouldn’t sideline the great thinkers of the past since their ideas are an integral part of the striving for freedom. By the same token, conservatives should be open to how people of color have revitalized many of those ideas.