Monday

Today, of course, is the day that America has been waiting for. It so turns out that, unlike much of the country, I am traveling away from where there will be a total eclipse (my mother lives 80 miles south of Nashville, the only North American urban epicenter). I’m visiting a sick friend in New York, where the eclipse will be less spectacular.

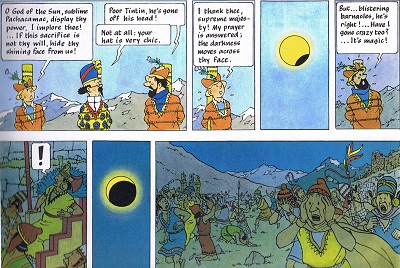

When I was growing up, I was fond of two stories where people use their knowledge of eclipses to engineer miraculous escapes. One was Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, the other Hergé’s Prisoners of the Sun, a Tintin adventure that I originally knew only in French. In both works, the knowledge proves the superiority of Western science over primitive peoples. It also saves the protagonists from being burned at the stake.

Claims of superiority are problematic in Tintin’s case because the Incas studied the sun and the moon closely and knew all about eclipses. To his credit, Hergé came to realize this later in life and regretted his stereotyping.

It may well be, however, that King Arthur’s court would not have understood eclipses. While Stonehenge, which works as an eclipse predictor, would have been available to them, they may not have been able to read it. Therefore Hank is able to convince Camelot that he has great powers.

Like the accomplished con man that he is, he does the necessary groundwork to insure that the event transpires with maximum effect. He relays a message to the court via the page Clarence:

“Now then, I will tell you what to say.” I paused, and stood over that cowering lad a whole minute in awful silence; then, in a voice deep, measured, charged with doom, I began, and rose by dramatically graded stages to my colossal climax, which I delivered in as sublime and noble a way as ever I did such a thing in my life: “Go back and tell the king that at that hour I will smother the whole world in the dead blackness of midnight; I will blot out the sun, and he shall never shine again; the fruits of the earth shall rot for lack of light and warmth, and the peoples of the earth shall famish and die, to the last man!”

Despite his foreknowledge, Hank has a couple of anxious moments before the eclipse occurs and he is freed. When the moment comes, however, he knows how to milk it:

I followed their eyes, as sure as guns, there was my eclipse beginning! The life went boiling through my veins; I was a new man! The rim of black spread slowly into the sun’s disk, my heart beat higher and higher, and still the assemblage and the priest stared into the sky, motionless. I knew that this gaze would be turned upon me, next. When it was, I was ready. I was in one of the most grand attitudes I ever struck, with my arm stretched up pointing to the sun. It was a noble effect. You could see the shudder sweep the mass like a wave.

To Mark Twain’s credit, he doesn’t allow the supposed superiority of Western science and technology to go unchallenged. True, between Hank’s astronomical knowledge and his grasp of technology, he is able to become a virtual dictator (he has people call him “the Boss”). Rather than successfully create the utopia that he dreams of, however, he discovers that rapid change backfires. The Enlightenment ultimately proves powerless in the face of custom and religion (superstition, as Hank sees it), and by the end Hank is engaging ins mass slaughter. His killing then rebounds on him as his own men die from the rotting corpses that surround and trap them. This is what technological hopes for the future come to, the cynical Twain indicates.

But back to our eclipse. Cataclysmic or prophetic though the event might have appeared to other times and places, we have a rational explanation for its appearance. Furthermore, we are beneficiaries of the science that warns us not to look directly at the eclipse, which would lead to cell damage. Those out there who are questioning evolution and climate change and yet are still buying eclipse glasses and traveling long distances—why are you so selective about when you believe scientists and when you don’t?