Spiritual Sunday

Last month I posted on a wonderful Alice Munro short story, “The Age of Faith,” about a girl wrestling with issues of faith. In today’s post I look specifically at the protagonist’s experience with the town’s Anglican church since I myself am Anglican (or, as we call it in America, Episcopalian).

Most of the citizens in the Canadian town of Jubilee attend the United Church, whose congregation is made up of “former Methodists and Congregationalists and a good chunk of Presbyterians.” Del is frustrated, however, that while she wants to know whether God exists or not, her church focuses only on “what He approved of, or usually…what He did not approve of.” She does not feel that she can talk to anyone about this, however:

I did not think of taking my problem to any believer, even to Mr. McLaughlin the minister. It would have been unthinkably embarrassing. Also, I was afraid. I was afraid the believer might falter in defending his beliefs, or defining them, and this would be a setback for me. If Mr. McLaughlin, for instance, turned out to have no firmer a grasp on God than I did, it would be a huge though not absolute discouragement. I preferred to believe his grasp was good, and not try it out.

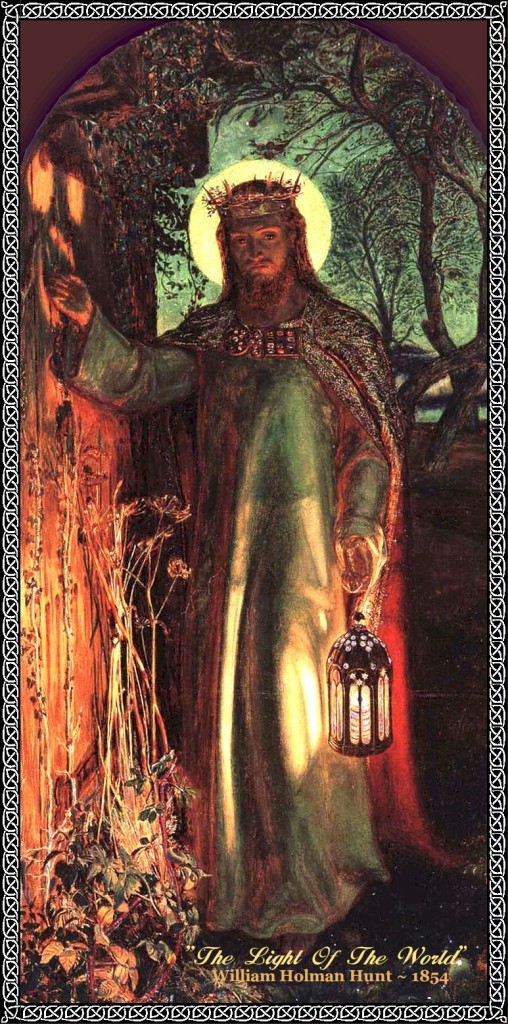

She chooses instead to try out a different denomination and chooses the Anglican church because it has a bell. Upon entering it, she is struck by William Holman Hunt’s famous painting of Christ knocking at the door (see above), the original of which is to be found in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London:

I had not seen this picture before. The Christ in it differed in some small but important way from the Christ performing miracles in the United Church window. He looked more regal and more tragic, and the background against which he appeared was gloomier and richer, more pagan somehow, or at least Mediterranean. I was used to seeing him limp and shepherdly in Sunday-school pastels.

What really captures Del’s attention, however, is the rich Anglican liturgy and all the ceremony involved. For instance, she is struck by the statement of confession, which turned me off when I recited it as a child. To one like myself who always wanted to please people in authority and who felt that I was always doing things wrong, it simply fed my general sense of unworthiness:

We have left undone those things which we ought to have done, And we have done those things which we ought not to have done. And there is no health in us. But thou, O Lord, have mercy upon us, miserable offenders. Spare thou them, O God, which confess their faults. Restore thou them that are penitent; According to thy promises declared unto mankind in Christ Jesu our Lord….

I can report that the Episcopal Church has since changed to a much more benign confessional prayer, perhaps because people felt that that the old one sounded too punitive and grim. As a result of the change, reciting the confession has become one of my favorite moments in the church service, a chance to reflect upon the past week and figure out how I could have had a more open heart and been a better neighbor:

Most merciful God, we confess that we have sinned against you in thought, word, and deed, by what we have done, and by what we have left undone.We have not loved you with our whole heart; we have not loved our neighbors as ourselves. We are truly sorry and we humbly repent. For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ, have mercy on us and forgive us; that we may delight in your will, and walk in your ways, to the glory of your Name.

What suffocated me, however, is what attracts Del:

So here was what I had not known, but must always have suspected, existed, what all those Methodists and Congregationalists and Presbyterians had fearfully abolished—the theatrical in religion. From the very first I was strongly delighted. Many things pleased me—the kneeling down on the hard board, getting up and knelling down again and bobbing the head at the altar at the mention of Jesus’ name, the recitation of the Creed which I loved for its litany of strange splendid things in which to believe. I liked the idea of calling Jesus Jesu sometimes; it made Him sound more kingly and magical, like a wizard or an Indian god; I liked the HIS on the pulpit banner, rich, ancient, threadbare design. The poverty, smallness, shabbiness, and bareness of the church pleased me, that smell of mold or mice, frail singing of the choir, isolation of the worshippers. If they are her, I felt, then it is probably all true. Ritual which in other circumstances might have seemed wholly artificial, lifeless, had here a kind of last-ditch dignity. The richness of the words against the poverty of the place. If I could not quite get a scent of God then at least I could get the scent of His old times of power, real power, not what He enjoyed in the United Church today; I could remember His dim fabled hierarchy, His lovely moldered calendar of feasts and saints. There they were in the prayer book, I opened on them by accident—saints’ days. Did anybody keep them? Saints’ days made me thing of something so different from jubilee—opens mows and half-timbered farmhouses and the Angelus and cancles, a procession of nuns in the snow, cloister walks, all quiet, a world of tapestry, secure in faith. Safety. If God could be discovered, or recalled, everything would be safe. Then you would see things that I saw—just the dull grain of wood in the floor boards, the windows of plain glass filled with thin branches and snowy sky—and the strange anxious paint that just seeing things could create would be gone. It seemed plain to me that this was the only way the world could be borne, the only way it could be borne—if all those atoms, galaxies of atoms, were safe all the time, whirling away in God’s mind. How could people rest, how could they even go on breathing and existing, until they were sure of this? They did go on, so they must be sure.

As I mentioned in my other post on the story, Del’s faith does not hold when it is really tested. In some ways, the exoticism of the Anglican rituals, which seems to hold so much promise, aren’t rooted deeply enough for Del and so can’t survive the hard knocks of tragedy. That sometimes happens when one goes journeying into a set of rituals which are not one’s own. They fail to sustain.