Wednesday

My novelist and poker-playing friend Rachel Kranz is allowing me to share posts from her blog Adventures in Poker this summer. Here’s one of her latest, which is a substantive exploration of envy. She draws on Dante to get at the nature of this particular deadly sin. To further her point that envy is the one deadly sin that gives no pleasure at all, I turn to Christopher Marlowe’s description in Doctor Faustus, where Envy describes himself as never happy but obsessed with the success of others:

Envy: I am Envy, begotten of a chimney-sweeper and an oyster-wife. I cannot read, and therefore wish all books were burnt. I am lean with seeing others eat. O, that there would come a famine through all the world, that all might die, and I live alone! then thou shouldst see how fat I would be. But must thou sit, and I stand? come down, with a vengeance!

Envy: The One Deadly Sin That Gives No Pleasure at All

By Rachel Kranz

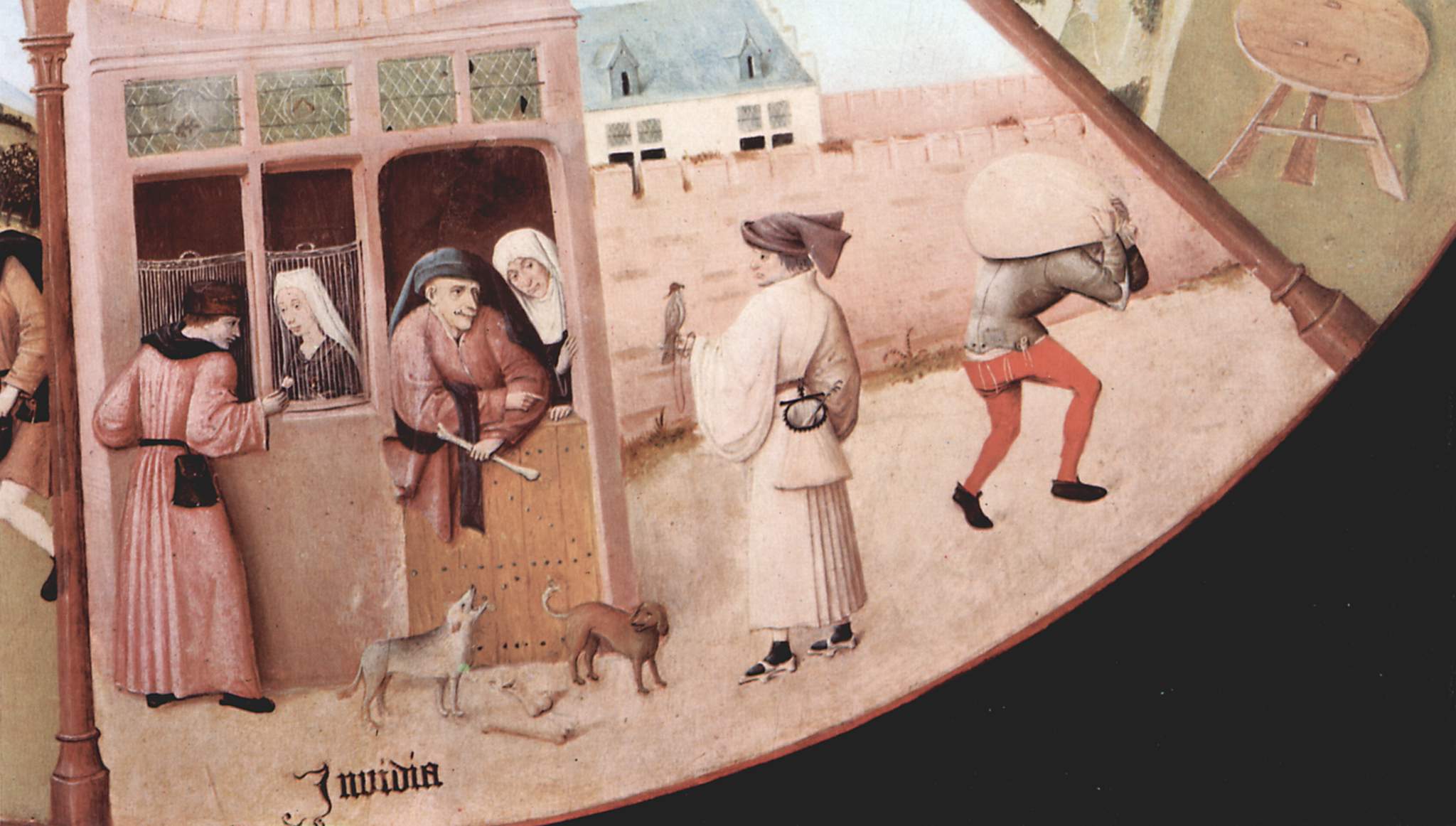

. . . envy is so integral and painful a part of what animates human behavior in market societies that many people have forgotten the full meaning of the word, simplifying it into one of the symptoms of desire. . . . But envy is more or less than desire. It begins with the almost frantic sense of emptiness inside oneself, as if the pump of one’s heart were sucking on air. One has to be blind to perceive the emptiness, of course, but that’s what envy is, a selective blindness. Invidia, Latin for envy, translates as “nonsight,” and Dante had the envious plodding along under cloaks of lead, their eyes sewn shut with leaden wire. What they are blind to is what they have, God-given and humanly nurtured, in themselves.

–Nelson Aldrich, Old Money

Scrolling through Twitter after busting from today’s WSOP tournament, I saw that two other players I know busted around the same time. But instead of coming to the Wynn to have dinner, as I did, they dashed over here to buy into Day 1d of the $1100 event, the one with $500k guarantee.

I would have loved to have played that tournament! But by the time I found out about it, entry had just closed, and my sense of agonized loss is a bit startling. Maybe that would have been my big score—and what a great structure—and all that dead money on Day 1d—and it would have been so much fun to play. . . Instead, I’m stuck with a night off tonight and a day off tomorrow, which, granted, I can make good use of—writing, food shopping, bill paying, poker studying, not to mention all the friends I’ve been meaning to call. . . Yeah, yeah, yeah. I’d rather be in the tournament.

Envy isn’t my only emotion. I really would have enjoyed playing, plus I wanted another chance to win some money. No question, though, that knowing the names of two other players (not even friends!) sharpened my regret to a much deadlier point. They get to—but I don’t…

Envy is probably as common a sickness during the WSOP as the infamous Rio flu. Although people tweet their busts and bad beats and frustrations—increasingly so as the summer wears on—we don’t really grasp that the vast majority of players are doing as badly as or even worse than we are. Instead we fixate on the five or eight or twenty who are actually winning events or at least bagging five-figure scores. If we had substantial success last summer, we fixate on how we used to be winners but now we’re losing—that is, we envy ourselves. Winning becomes not the one-in-a-thousand shot that math and common sense insist is our true chance of taking first in a large-field tourney. Instead, it’s the will o’ the wisp that’s always just beyond our grasp.

Will o’ the wisps are the emission of gases found in marshy land or swamps. Faintly glowing, they hang suspended in the air, as if alive and full of meaning. In folklore, they’re the glowing coals carried by various lost souls (Drunk Jack or—I’m not making this up!—Will the Smith), men doomed to wander in a twilight world—neither day nor night, neither alive nor dead, neither heaven nor hell—as they lure unsuspecting travelers into the swamp.

That big score each of us is chasing is no myth—it’s as solid as a gold bracelet, real as a retirement fund (unless the stock market collapses—but, hey, one will o’ the wisp at a time!). And yet, there I am, a lost soul wandering into the swamp, my eyelids sewn shut, a leaden weight upon my heart. As Aldrich says, I feel empty because I am blind, seeing not the moments of divine play, but only the missing result; seeing not the luminous decisions, the glittering strategy, the spacious, timeless realm of the Zone, but only the amount of money I might have won—but didn’t. I don’t even see the less attractive possibilities—the story in which I rush over to the Wynn, fire two or three bullets, and end up playing two full days for a min-cash, $2000 poorer than when I began. Yes, I’d enjoy playing, maybe even more than anything else I’d do tomorrow. But it’s the lost fantasy that really rankles, all the more because other people still have a shot at it.

Envy is one of the seven deadly sins; the others are pride, avarice, lust, anger, sloth, and gluttony—which are at least fun! Only envy gives you no pleasure at all. In vidia—not seeing—why can’t I open my eyes?

Ironically, my envy is probably sharper this year precisely because I am so much happier with my play. For the past several years, every bust was a major drama. I’ve made a horrible mistake! How can I learn not to repeat it? What’s wrong with me? Why am I lost here in the swamp while everyone else is on solid ground?

Now I feel pretty happy with both my mental game and my strategy. Obviously I have more to learn—I always will—but the drama is gone. Most of the time, there’s no big problem to agonize over—I just didn’t get there. Like every single other player, I couldn’t crack the math that keeps the best of us from cashing more than 15 percent of the time or winning more than one time in a thousand. Okay, if I’m twice as good as the field, I’ve got two chances in a thousand—being three times as good gives me three chances. Most of the time, though, I’m stuck among the 997 no matter how good I am; as a mere human, I can’t transform the math but only myself. And transforming myself, while meaningful and worthwhile, is never really enough.

So maybe envy is there to help blind me to how powerless I am in the grand scheme of things, keeping me focused on the ones who seem to have enough power to beat the system instead of letting me see that, ultimately, none of us can. We’re born, we play, we die. That’s all we have—but when we stop following those will o’ the wisps and learn how to open our eyes, maybe that’s enough.