Thursday

When Ariel Dorfman talks, I listen. In a recent New York Times article, the Chilean who fled the Pinochet dictatorship in fear for his life, criticizes the punishment awaiting Iago at the end of Othello.

Dorfman, now a professor at Duke, first gained widespread attention with his How to Read Donald Duck, which is about Disney’s imperialist messages in his cartoons. Dorfman gained my respect when he spoke out against the U.S. invading Iraq. Even though Saddam Hussein was a murderous dictator who visited unimaginable tortures on his victims, Dorfman said that preemptive war against him was wrong and would lead far greater bloodshed. Dorfman had credibility because of his intimate knowledge of dictators torturing people, and he proved to be right as well.

In his recent Times article, Dorfman addresses an upcoming court case brought by three people who were tortured by the CIA under the Bush administration. The defendants are the two psychologists

who devised the “enhanced interrogation techniques” that became the basis for the C.I.A. torture program described in shocking detail in the Senate Intelligence Committee’s 2014 report.

This case leads Dorfman to contemplate the punishment meted out to Iago at the end of Othello.

Dorfman is concerned that, following another terrorist attack, we might return to torturing people:

Donald Trump vowed, during his campaign, to bring back waterboarding “and a hell of a lot worse.” As yet, we have not seen that “worse,” since the counsel of his defense secretary, James Mattis — that such methods are useless and counterproductive — has prevailed. At least, as far as we know. It is not hard to imagine that a major terrorist attack is all it would take to revive such maltreatment. A recent survey found that almost half of Americans approved the use of torture if it led to information being extracted.

Dorfman says that he understands collective panic but that he has first hand knowledge of how torture contaminates everything:

But for those of us, like my wife and me, who lived through the ouster of President Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973, and witnessed the murderous regime of Gen. Augusto Pinochet, the damage inflicted by torture — not just physically on individuals, but psychologically on an entire nation — is deeply corrosive.

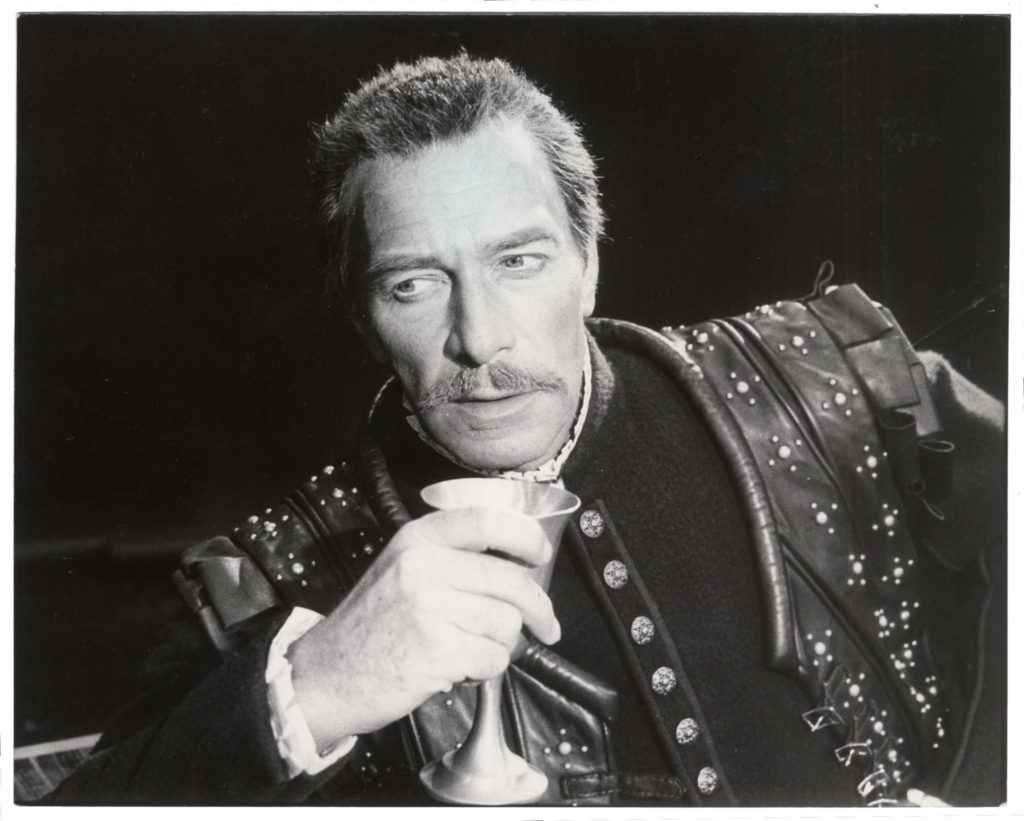

Dorfman then uses Iago as a test case. Perhaps no character seems more deserving of extreme punishment in Shakespeare’s plays than Iago. In fact, if one looks at the source material, one realizes that Shakespeare stripped away any mitigating factors so that Iago seems spurred by nothing but pure malevolence.

Thus, the audience may take at certain satisfaction in Iago’s promised end:

For this slave,

If there be any cunning cruelty

That can torment him much and hold him long,

It shall be his.

Dorfman lays out what fate spectators at the time could have imagined for Iago:

In 1595, for example, a Jesuit priest and poet accused of treason, Robert Southwell, was strung up at Tyburn. He was sentenced to be disemboweled while still alive, and his corpse ended up quartered, his head cut off, before a large, ogling crowd. Before his execution, Southwell witnessed in prison men “hanged by the handes eight or nine houres, yea twelve houres together, till not only their wits, but even their senses fayle them.” Other horrors he described were bodies broken on the rack, genital mutilation and starvation so severe that inmates would lick “the verye moisture of the walls.”

I must say that, when I first read the play in high school, I too took a certain satisfaction in what was going to happen to Iago, although I didn’t have this detailed information about Elizabethan Age tortures.

Dorfman’s point is that, while Iago may richly deserve punishment, torturing him rebounds on all of us:

Only when we have the moral courage to declare that someone like Iago, who has done so much harm, should not be put on the rack or have his genitals slashed or be forced to open his lips and scream and scream … only then, when we understand that hurting him in this way degrades us all, will we have advanced toward banishing this plague of cunning cruelty from the earth. I fear that day will be a long time coming.

As long as we remain trapped by the desire for reckoning and revenge, we avoid the most difficult truth about Iago: He is human, and enjoys as his birthright certain inalienable rights. This monster who planned the ruin of Othello and Desdemona with the cold, deliberate passion of a suicide bomber, happens, alas, to be a member of our species — an extreme litmus test for that species.

From such a perspective, Dorfman argues that we shouldn’t be arguing about whether torture works or not. We should be examining what torture does to those who approve:

The argument that we should abolish torture because it does not work may be the wrong one. The question that Iago asks all these centuries later is how torture works on us, what it does to our humanity, when we look on approvingly as his malignant body is taken away to suffer unspeakable pain.