Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Spiritual Sunday

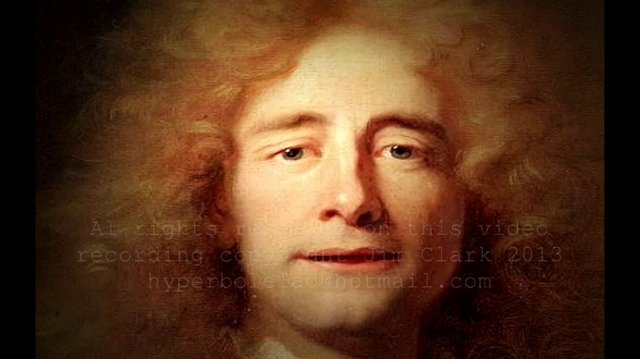

For our Lenten study, our church is reading Green Gospel: Foundations of Ecotheology, by my dear friend and colleague John Gatta. Among other things, the book is giving me a new respect for the 17th century poet Thomas Traherne, who plays a key role in the book. More on Traherne in a moment.

First, however, to John’s thesis, which is that Christianity and environmentalism can complement and feed each other. That’s in part because Christianity does not apply only to human beings. John writes,

Faith must encompass everything—all things seen and unseen, human and nonhuman beings of every stripe, throughout the whole of creation. For us living today, a Jesus capable of rescuing just ourselves, or our kind alone, from sin and death can no longer be recognized as God’s savior of the world. Only a cosmic Christ, as Saint Paul first envisioned, could possibly fulfill that role.

Extending the idea of salvation to nonhumans as well as humans is central to Green Gospel. As John notes, God didn’t just create the universe and then sit back. Rather, God is incarnate within the evolving universe, simultaneously within it and beyond it. This, John says, is the meaning of the trinity, which captures this paradoxical situation:

The vision of a Triune God contributes most critically toward shaping a robust ecotheology, I believe, by holding together, in creative and paradoxical tension, two seemingly contrary notions of the Godhead. Or as [Jürgen] Moltmann puts it, the “trinitarian concept of creation binds together God’s transcendence and immanence,” thereby conjoining the partial, opposite truths represented both in radical monotheism and in a pantheism that would virtually equate Nature with divinity.

The idea of God having created a blueprint in which everything is foreseen, John says, is ironically similar to 18th century deist notions of God as a clockmaker winding up the giant clock of creation. John says that those Christian fundamentalists who embrace the theory of intelligent design, and with it attack attack scientific theories of evolution, turn God into a “lifeless, loveless, and cheerless” being or force:

Far from bolstering esteem for the Creator-God, the ideology of intelligent design fails to recognize the richly creative, cooperative, and dynamic force inherent in the Creator’s inspiration of evolutionary processes. Even if we affirm, in faith, that God is the first cause and ground of all creation, we must acknowledge—as intelligent design does not—the substantial role and freedom that God has allowed within the cosmic drama for all manner of secondary causes and chance developments. Such causes, though sometimes agents of sorrow and malignancy, also infuse into existence a welcome color, variety, beauty, and unanticipated marvels.

In sum, the Creator-God of intelligent design is not genuinely creative—not, at least, by analogy with the sublime expressions of creativity we have come to recognize in great literary authors, composers, public leaders, and painters. Nor is the Designer-God artistic, vital, original, or playful. What this God designs, in figurative essence, is just a series of static blueprints, destined for sequential realization in the material realm. These preconceived blueprints for the design of all creaturely existence might be correct in every detail but comparatively lifeless, loveless, and cheerless in their conception.

A number of poets have seen God is simultaneously prime mover and incarnate in nature, including William Blake (“to see heaven in a wild flower”) and Alfred Lord Tennyson (“Little flower—but if I could understand/ What you are, root and all, and all in all,/ I should know what God and man is”). But one doesn’t need theology or poetry to realize this. Think of times in your own life when you have looked at nature and experienced a sense of the divine, even while knowing at the same time that natural scientific processes were at work.

But while we can know this without poetry, poetry clarifies and intensifies the vision. Take, for instance, Traherne’s poem “The Sand Is Endless,” where he writes,

In all Things, all Things service do to all:

And thus a Sand is Endless, though most small.

And every Thing is truly Infinite,

In its Relation deep and exquisite.

In “Dumbness,” meanwhile, he writes,

And every stone, and every star a tongue,

And every gale of wind a curious song.

The Heavens were an oracle, and spake

Divinity: the Earth did undertake

The office of a priest…

Finally, there’s Traherne’s beautiful poem “Walking,” clearly written by someone who treasures the activity. At one point the poet writes,

To note the beauty of the day,

And golden fields of corn survey;

Admire each pretty flow’r

With its sweet smell;

To praise their Maker, and to tell

The marks of his great pow’r.

Traherne wants us to pay attention when we venture out into nature. Otherwise, we are no more than “dead puppets” whose

silent feet,

Like logs of wood,

Move up and down, and see no good

Nor joy nor glory meet.

Here’s the poem:

Walking

By Thomas Traherne

To walk abroad is, not with eyes,

But thoughts, the fields to see and prize;

Else may the silent feet,

Like logs of wood,

Move up and down, and see no good

Nor joy nor glory meet.

Ev’n carts and wheels their place do change,

But cannot see, though very strange

The glory that is by;

Dead puppets may

Move in the bright and glorious day,

Yet not behold the sky.

And are not men than they more blind,

Who having eyes yet never find

The bliss in which they move;

Like statues dead

They up and down are carried

Yet never see nor love.

To walk is by a thought to go;

To move in spirit to and fro;

To mind the good we see;

To taste the sweet;

Observing all the things we meet

How choice and rich they be.

To note the beauty of the day,

And golden fields of corn survey;

Admire each pretty flow’r

With its sweet smell;

To praise their Maker, and to tell

The marks of his great pow’r.

To fly abroad like active bees,

Among the hedges and the trees,

To cull the dew that lies

On ev’ry blade,

From ev’ry blossom; till we lade

Our minds, as they their thighs.

Observe those rich and glorious things,

The rivers, meadows, woods, and springs,

The fructifying sun;

To note from far

The rising of each twinkling star

For us his race to run.

A little child these well perceives,

Who, tumbling in green grass and leaves,

May rich as kings be thought,

But there’s a sight

Which perfect manhood may delight,

To which we shall be brought.

While in those pleasant paths we talk,

’Tis that tow’rds which at last we walk;

For we may by degrees

Wisely proceed

Pleasures of love and praise to heed,

From viewing herbs and trees.

So go take a walk.