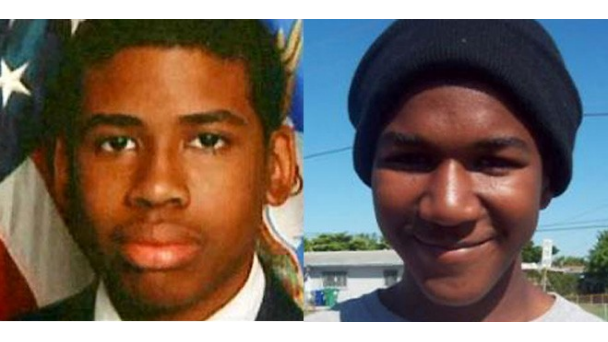

So we have another appalling trial verdict allowing a white man to get away with shooting an innocent black teenager. Although the jury’s hung verdict leaves open the possibility for another trial and although Michael Dunn may go to jail for life for the other counts against him (attempted murder for firing at the other three youths in the car as they fled), his killing of 17-year-old Jordan Davis was the latest graphic instance of “stand your ground” at work.

As a number of people have pointed out, if Dunn had killed everyone in the car, he might have gotten off. Others have noted that the law appears to be a successor to the old lynching laws: if a white feels threatened by a black man, it is his or her right to kill him.

Of course the law is understood to sanction only white on black violence, not black on white. Responding to an earlier killing, Barack Obama asked what we all recognize as a rhetorical question: “If Trayvon Martin was of age and was armed, could he have stood his ground on that sidewalk?”

After the verdict was announced, I found myself thinking, “Everybody wants a black man’s life.” The line is from Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon (1977) so I went back to check the context.

One of Obama’s favorite books, Song of Solomon is the account of a young black man of privilege (Milkman) who doesn’t know what he wants in life. He embarks upon what becomes a roots quest, but before he does so, he has a serious talk with his one-time best friend Guitar, who has become obsessed with killing innocent whites as payback for the killing of innocent Blacks. Here’s Guitar:

Look. It’s the condition our condition is in. Everybody wants the life of a black man. Everybody. White men want us dead or quiet—which is the same thing as dead. White women, same thing. They want us, you know, “universal,” human, no “race consciousness.” Tame, except in bed. They like a little racial loincloth in the bed. But outside the bed they want us to be individuals. You tell them, “But they lynched my papa,” and they say, “Yeah, but you’re better than the lynchers are, so forget it.”

In his quest Milkman experiences what Joseph Campbell would describe as a belly-of-the-whale moment: alone in a dark wood, he questions his identity and takes stock of his life. This occurs when he finds himself, improbably, involved in a night hunt for a bobcat. During the hunt, he almost dies—and speaking metaphorically, he does die, coming back to life with a new love of life and a new sense of purpose. In the killing and skinning of the bobcat he sees, in all its clarity, his own situation. (His last name is Dead.) This blunt assessment of his condition is the first necessary step to envisioning new possibilities for himself.

He thinks of Guitar’s words as he watches his fellow hunters skin the bobcat. The scene is a tour-de-force. On the one hand, it captures without flinching the violence that is being enacted upon black men. (Earlier in the novel there are references to the Emmett Till lynching, and we ourselves can think of Trayvon and Jordan.) On the other, by joining Guitar’s framework to multiple genital references, it indicates how whites, threatened by black masculinity, seek to emasculate young black men:

Omar sliced through the rope that bound the bobcat’s feet. He and Calvin turned it over on its back. The legs fell apart. Such thin delicate ankles.

“Everybody wants a black man’s life.”

Calvin held the forefeet open and up while Omar pierced the curling hair at the point where the sternum lay. Then he sliced all the way down to the genitals. His knife pointed upward for a cleaner, neater incision.

“Not his dead life; I mean his living life.”

When he reached the genitals he cut them off, but left the scrotum intact.

“It’s the condition our condition is in.”

Omar cut around the legs and neck. Then he pulled the hide off.

“What good is a man’s life if he can’t even choose what to die for?”

The transparent underskin tore like gossamer under his fingers.

Everybody wants the life of a black man.”

Now Small Boy knelt down and slit the flesh from the scrotum to the jaw.

“Fair is one more thing I’ve given up.”

Luther came back and, while the others rested, carved out the rectal tube with the deft motions of a man coring an apple.

“I hope I never have to ask myself that question.”

Luther reached into the paunch and lifted the entrails. He dug under the rib cage to the diaphragm and carefully cut around it until it was free.”

“It is about love. What else but love? Can’t I love what I criticize?”

Then he grabbed the windpipe and the gullet, eased them back, and severed them with one stroke of his little knife.

“It is about love. What else?”

They turned to Milkman. “You want the heart?” they asked him. Quickly, before any thought could paralyze him, Milkman plunged both hands into the rib cage. “Don’t get the lungs, now. Get the heart.”

“What else?”

He found it and pulled. The heart fell away from the chest as easily as yolk slips out of its shell.

“What else? What else? What else?”

Grabbing the heart is important. Guitar claims to love blacks, but he has allowed white racism to so twist his heart that he turns to violence, not only against innocent whites but also against Milkman, his best friend.

Milkman, by contrast, is asking, “What else?” What other possibilities are there? In the course of his subsequent roots quest, he will discover he has a large heart—for his ancestors, for the people in his life, even for his friend who is trying to kill him. When Guitar guns down his aunt, Milkman hears her say, “I wish I’d a knowed more people. I would of loved ’em all. If I’d a knowed more, I would a loved more.”

As Aunt Pilate dies in Milkman’s arms, Morrison writes,

Now he knew why he loved her so. Without ever leaving the ground, she could fly. “There must be another one like you,” he whispered to her. “There’s got to be at least one more woman like you.”

The flying images point to something bigger than hatred. Morrison contends that black solidarity and black love will carry the day.

When I look at the families of Trayvon and now of Jordan, I am struck by their strong determination not to be defined by the hatred of George Zimmerman and Michael Dunn. Even as vile racist voices in the culture and in the rightwing media seek to characterize their sons as thugs, these families focus on the light.

Morrison’s book too ends with a leap into the light, a black man not having his life taken but risking that life instead to advance into an unknown future. It’s a dazzling conclusion with an element of magical realism that allows us to imagine something beyond imagining: something other than Guitar’s revenge can arise out of these heartrending tragedies. The scene has Guitar with his rifle on one crag and Milkman on a facing one. “Shalimar” is Milkman’s slave ancestor who, according to legend, flew back to Africa:

Milkman stopped waving and narrowed his eyes. He could just make out Guitar’s head and shoulders in the dark. “You want my life?” Milkman was not shouting now. “You need it? Here.” Without wiping away the tears, taking a deep breath, or even bending his knees—he leaped. As fleet and bright as a lodestar he wheeled toward Guitar and it did not matter which one of them would give up his ghost in the killing arms of his brother. For now he knew what Shalimar knew. If you surrendered to the air, you could ride it.

Innocent black men may die, but flight is still possible.

One Trackback

[…] “Everybody Wants a Black Man’s Life,” reprinted from BLTB, Feb. 24, 2014 […]