Monday

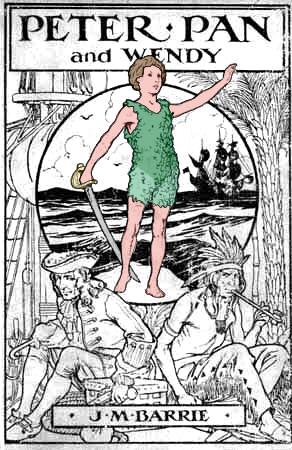

Teaching James Barrie’s Peter and Wendy last week in my British Fantasy class proved to be an emotional experience for me. That’s because I gained a new perspective on how my father raised me and my brothers. Like Barrie, he turned to fantasy to hold off the darkness that he saw in the world.

Scott Bates held on to a child’s playfulness up until he died two years ago at 90. When we were children, he regularly supplied us with games. We had Frisbees (when they first became popular), French boules, bocce balls, diabolos, and yo-yos, and he always carried marbles and tops in his pocket to amuse children. When he built his house, he installed a flat roof where we played badminton and ring toss, and he laid out a concrete slab for shuffleboard. He also installed a horseshoe pit in the yard, while inside we had a foosball table, a Ping-Pong table, caroms, and skittles. We never got a billiard table but he always dreamed of one.

Above all, he read stories and poems to us (including Peter and Wendy) until we were well into middle school. He reveled in our childhood as Barrie did with Peter Davies, the model for Pan.

But Peter and Wendy is not all flying and fairy dust, and my students were struck by the violence. Tinker Bell persuades the Lost Boys to shoot Wendy, there’s a battle where the pirates massacre many of the Indians, and Captain Hook makes regular use of his hook. We even learn that Peter may kill other boys, as in the following passage. It occurs when everyone is circling the island at the same pace, with the wild beasts stalking the Indians who are stalking the pirates who are stalking the Lost Boys:

All wanted blood except the boys, who liked it as a rule, but tonight were out to greet their captain. The boys on the island vary, of course, in numbers, according as they get killed and so on; and when they seem to be growing up, which is against the rules, Peter thins them out; but at this time there were six of them, counting the twins as two.

And here’s a description of Captain Hook:

His eyes were of the blue of the forget-me-not, and of a profound melancholy, save when he was plunging his hook into you, at which time two red spots appeared in them and lit them up horribly. In manner, something of the grand seigneur still clung to him, so that he even ripped you up with an air, and I have been told that he was a raconteur of repute….

Let us now kill a pirate, to show Hook’s method. Skylights will do. As they pass, Skylights lurches clumsily against him, ruffling his lace collar; the hook shoots forth, there is a tearing sound and one screech, then the body is kicked aside, and the pirates pass on. He has not even taken the cigars from his mouth.

Such violence is not uncommon in children’s books, from Lewis Carroll’s Queen of Hearts to the grisly fates meted out to various children in the Roald Dahl books to the torture and killing in Harry Potter. This may at first seem surprising until one realizes that people, adult authors and children alike, turn to fantasy as a shield against a reality that they find intolerable. Great fantasy owes its power to the struggle, with a version of that reality always showing up in the story.

Barrie certainly used fantasy this way. When he was six, his older brother died in an ice skating accident and his mother never recovered. To console her, James would read books to her. His love of stories and playacting became so rooted that he resisted family plans for him to become a minister. He dutifully went to college but worked out a compromise where he could major in literature. Then he followed his own path and became a writer. Many of his best friends were children.

One sees his longing to hold onto his childhood in Peter and Wendy. In addition to Peter, there is Hook, who is angry that he is growing up and losing the “good form” that comes naturally to children. Hook is haunted by the ticking clock in the crocodile, a sign of time passing. Like Peter, he wants Wendy to mother him. Meanwhile, in the Darling household Mr. Darling doesn’t like being an adult and can be just as childish as Michael, the youngest.

My father wasn’t childish in this way but he definitely tried to hold on to a sense of innocence. Most of the books he read to us were fantasy, and I remember him sometimes skipping endings where the characters return to the real world. For instance, he hated the final chapter of The House on Pooh Corner, and I don’t believe he read us the ending of Peter and Wendy. He did read us the tragic ending of Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court but I think was disturbed by how badly we took it.

One sees some of the playfulness in his light verse, much of which I’ve shared over the life of this blog. Although poet Karl Shapiro, his poetry teacher at the University of Wisconsin, once told him that he couldn’t be a great poet if he wrote light verse, light verse is pretty much all that he wrote.

I vividly remember my father’s cardinal rule for us: we were not allowed to “burst someone’s bubble.” If one of us was feeling good about an accomplishment, we weren’t to go undercutting it. When I was older, my father talked to me about “the desecration of innocence.” In his eyes, few things worse than that.

The more I researched Barrie’s life, the more parallels I found. Barrie was the second youngest of nine children and, like my father, had two older brothers who were the family’s pride and joy. As with Barrie, fewer hopes were invested in my father, who was regarded as effeminate. After all, he wrote poetry, loved books, watched birds, wore glasses, was sickly at one point in his life, and didn’t play sports. While my grandfather looked down on him, however, my grandmother (“Granny”) found him sweet and dressed him as Little Lord Fauntleroy, complete with velvet and lace collarsm when he was young. He bonded with her as Barrie did with his own mother.

Imagine someone with this childhood landing in German-occupied France a week after turning 21. I think my father tried to hold on to his childhood innocence to cushion himself against the shock of World War II. While he didn’t engage in any fighting, he witnessed German bombing in the Battle of the Falaise Gap and he saw Dachau three days after it was liberated. In fact, he was assigned to take Germans to the camp to persuade them that the Holocaust was not just American propaganda.

He came back from the war an atheist and a material determinist who saw the world slated for destruction. His poetry, humorous though it is, often has an undercurrent of pessimism. His children, however, gave him a chance to return to the innocence of childhood, and he returned the favor by being our generous playmate.

He was a wonderful father to have although we, or at least I, imbibed some of his fears about the world. To please him I tried to hold on to my own innocence for as long as I could. I buried myself in Tolkien and C. S. Lewis and I lashed out against Catcher in the Rye, which was assigned in high school and dramatizes the fall from innocence. Holden may fantasize about catching children before they run off the cliff into adolescence, but it’s a losing battle.

“All children, except one, grow up,” Barrie memorably writes. That doesn’t mean we accept it..

One Trackback

[…] learning a lot from my end-of-the-semester British Fantasy presentations. I’ve written before about the violence in Peter and Wendy, and through one student’s engagement with the book, I […]