Friday

I share today a new insight that I gained from my recent Lifelong Learning class about “Wizards and Enchantresses.” To set it up, I first share my theory of fantasy.

As I see it, fantasy is always oppositional in its invocation of magic and the supernatural. If it flourished in the wake of the scientific and technological revolutions, that’s because it was pushing back against science’s narrow focus on the material world. People were (and are) hungry for something more.

Therefore, the gothic novel arose in the mid-18th century when the Enlightenment was at its height, and it has been going strong ever since (Steven King is the world’s bestselling author). In the 19th century, the Grimm brothers collected fairy tales, Hans Christian Andersen wrote his own, Mary Shelley launched the monster novel ,and Tennyson brought back the Arthur tales. In the 20th century, J. R. R. Tolkien gave birth to the sword and sorcery genre, conceived in opposition to mechanized warfare and the rise of totalitarianism.

Now for the question I have long wrestled with: What are we to make of the fact that fantasy has always been popular, predating the Enlightenment by thousands of years? Even when people actually believed in ghosts and fairies, they still hungered for fantasy tales. Was fantasy oppositional for them as well?

I conclude that it was and owe my understanding to Chaucer’s Wife of Bath. At the beginning of her tale, she complains about Christian friars, who she says went through the land expelling fairies, elves, and other supernatural creatures:

In the old days of King Arthur,

Of whom Britons speak great honor,

This land was all filled full of supernatural creatures.

The elf-queen, with her jolly company,

Danced very often in many a green mead.

This was the old belief, as I read;

I speak of many hundred years ago.

But now no man can see any more elves,

For now the great charity and prayers

Of licensed beggars and other holy friars,

That overrun every land and every stream,

As thick as specks of dust in the sun-beam,

Blessing halls, chambers, kitchens, bedrooms,

Cities, towns, castles, high towers,

Villages, barns, stables, dairies --

This makes it that there are no fairies.

The Wife uses pre-Christian fantasy to imagine an alternative to a Christian misogyny that constrains her, which she counters with an Arthurian tale about a powerful fairy queen who effects a magical resolution. While all medieval Christians believed in magic, some magic was acceptable, some not. The Wife of Bath invokes unacceptable Celtic paganism when Christianity proves stifling.

Chaucer wasn’t the only author to do so. Geoffrey of Monmouth traces Merlin and Morgan Le Faye back to pre-Christian origins, and the author of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight gives us a sympathetic green man. For that matter, one finds Celtic green men carved into medieval churches all over England and Ireland.

It didn’t matter that the Christian church associated paganism with Satan. People couldn’t let go of symbols that expanded their vision.

Occasionally Christian fundamentalists went to extremes to “purify” the religion, as Puritans attempted to do in the 17th century. They banned Twelfth Night festivities (associated with the winter solstice) and maypole dancing (associated with the spring solstice) and chiseled off green man carvings (as they did in Manchester’s cathedral). Yet these old vestiges could not be entirely eradicated and, thanks to Walter Scott and Charles Dickens, a pagan Christmas came back stronger than ever in the 19th century.

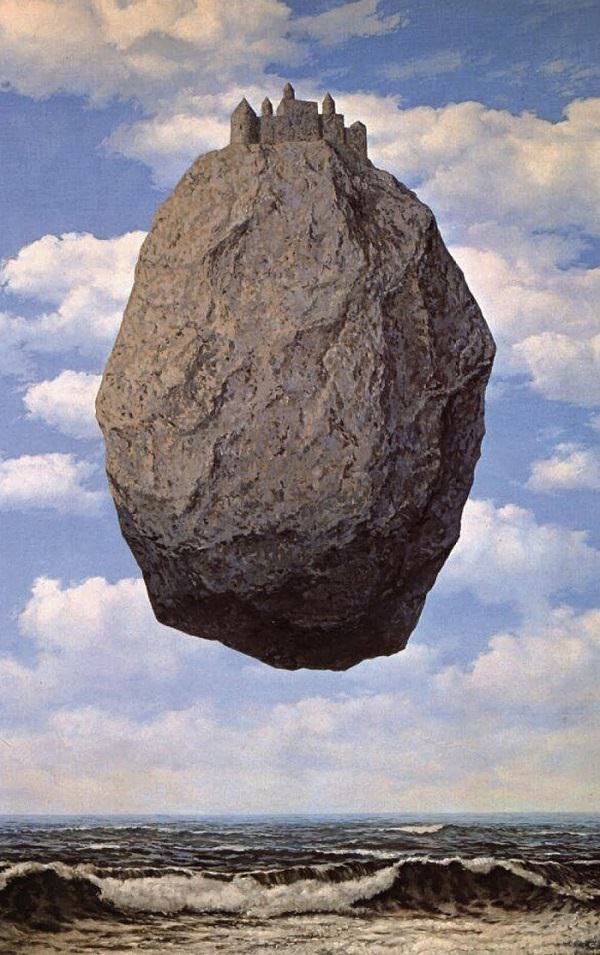

In other words, whenever orthodox belief attempts to constrict the imagination—whether it be religious belief or scientific belief—the imagination fights back with wondrous tales and images. Dogmatists and dull pragmatists dismiss these as “just fantasy.” The rest of us know better.