Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

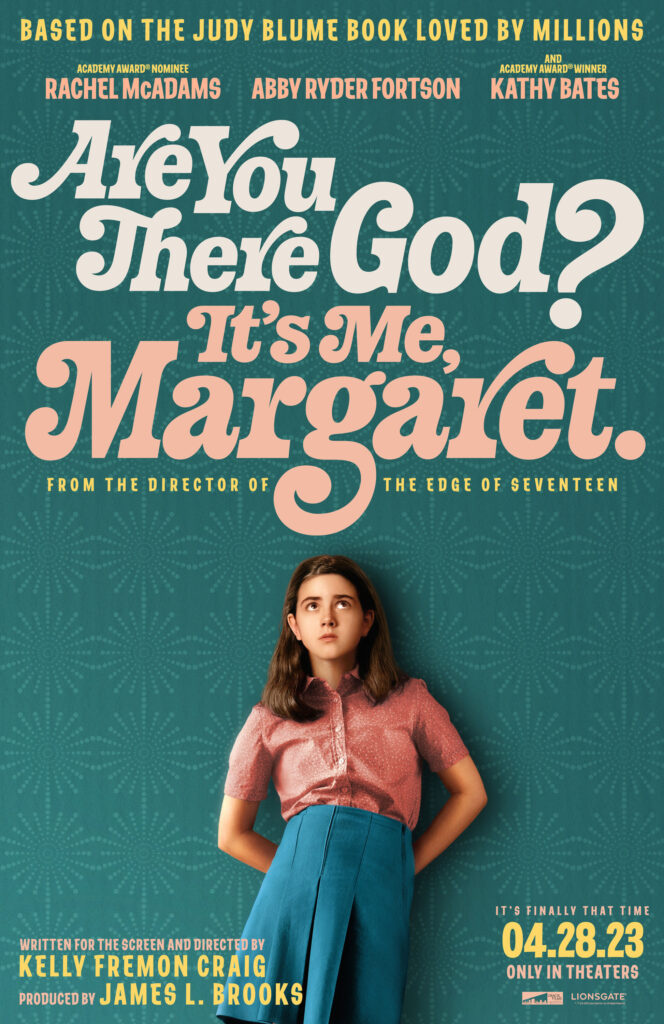

When I learned recently that GOP legislators in Florida were working on a bill that would prevent educators from talking about menstruation in elementary school (these days, it’s not uncommon for girls nine or ten to begin getting their periods), I immediately thought of Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. The novel, which features middle schoolers talking about the menstrual cycle, has long been popular amongst children—and that for the simple reason that it tells them things they need to know. That it does so with an interesting story and a relatable character makes it all the more powerful. For decades, stories have abounded of children secretly passing it around amongst themselves in schools where it has been banned.

In a recent Variety interview, Blume speaks forcefully about book bans of the sort we’re currently witnessing in Florida (where Blume lives) and in Texas. Blume knows a lot about such bans, having also seen them applied to her novel Deenie, where teenage girls learn about and engage in masturbation, and Forever, where a high school girl grapples with sexual anxieties before entering into her first serious relationship.

In other words, she writes books that speak to teenagers’ pressing concerns.

Blume says that censorship began to soar following Ronald Reagan’s election. Her first experience came when her children’s elementary school principal refused to put Margaret on the library shelves: “He believed that menstruation wasn’t a topic that girls should read about, never mind how many kids already had their periods.”

At least in the 1980s, however, censorship was not coming from the government. Today, Blume points out, librarians “can go to prison if [they are] found guilty of having pornography on their shelves. Try and define pornography today and you’ll find that it’s everything.”

Among the examples she cites is Jessica Love’s Julian Is a Mermaid, which is about a boy

who likes to dress up in fancy clothes, and he has a wonderful grandmother who has all kinds of beads and feathers. She’s supportive of him. If you go back to the ’80s, it was Heather Has Two Mommies [by Lesléa Newman]. That picture book was banned everywhere. Well, there’s a lot of kids who have two mommies or two daddies, and that book is important! Today, they’re considered pornographic by some legislatures.”

When legislators claim that they’re protecting kids, Blume asks,

What are you protecting your children from? Protecting your children means educating them and arming them with knowledge, and reading and supporting what they want to read. No child is going to become transgender or gay or lesbian because they read a book. It’s not going to happen.

Books prove valuable, Blume says, when a child says, “Oh, this is just like me. This is what I’m feeling and thinking about.” Or “I’m interested in this because I have friends who may be gay, bi, lesbian.”

Blume points out that such books teach empathy. Such was the effect on her of Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, which Blume notes is “probably the No. 1 banned book in America right now.” Blume’s response was that “this young person is telling me how they came to be what they are today. And I learned a lot…”

Which leads to the question of fighting back. Blume mentions the National Coalition Against Censorship, which she says is “right there on the front lines.” “If a teacher, librarian, parent or student needs help as books are being challenged in their classrooms,” Blume says, “NCAC is on the other end of the phone to help.”

A recent Washington Post column describes other ways to resist. It’s important in these battles, Alyssa Rosenberg points out, to remember that censorship

isn’t popular. Fifty-six percent of respondents to an August 2022 survey disagreed with the statement: “If any parent objects to a book in the public school library, that book should be removed, even if other parents like the book.” A poll published in March 2023 by Wall Street Journal-NORC found 61 percent were more concerned that “some schools may ban books and censor topics that are educationally important” than by the prospect that instructional materials might offend students or parents. That skepticism isn’t partisan, either.

What’s important, however, is that library advocates “tailor their campaigns to their communities.”

Rosenberg suggests, for instance, that

library supporters can point out that censorship has costs and wastes public resources. Libraries have been sued for removing books or restricting access to them on the grounds that it is illegal for public facilities to favor one political viewpoint over another. Towns can’t ban books because they’re Marxist, or use internet filters that restrict access to gay rights websites while letting users browse conversion therapy ministries. Even if a library or school system wins a case, defending it costs money, and damages can be substantial. Recently, reminders of the risks of litigation helped library advocates temper a censorship policy in League City, Tex.

Advocates can also point out that making librarians legally liable for distributing certain material can lead to higher municipal insurance costs. Also expensive are special tip lines since they tend to get flooded with witty anti-censorship spam.

Some book activists find ways to show that censorship cuts both ways:

One puckish censorship opponent in Utah challenged the Bible on the grounds that it contains “incest, onanism, bestiality, prostitution, genital mutilation, fellatio, dildos, rape, and even infanticide.” Talarico recently lamented that the Texas books bill could evict Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove from schools, denying students access to one of the masterworks of Texas literature.

And sometimes just showing up can matter:

That strategy paid off in Tammany Parish in Louisiana. A local woman challenged several books as being “harmful to minors.” She didn’t come to a crucial meeting about the volumes. People who believed the books were important did. The library control board voted to keep some of the targeted texts on shelves.

As always, the price of liberty is eternal vigilance. Books that open minds and change lives are at stake.