Spiritual Sunday

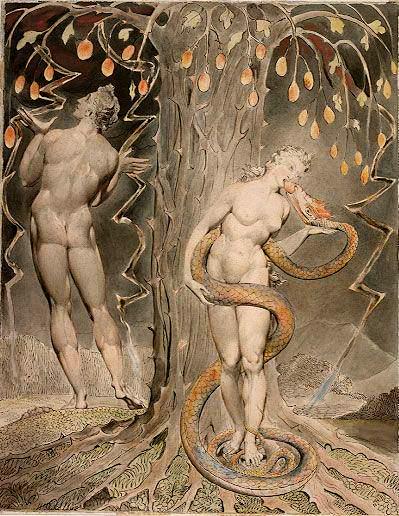

Today’s Old Testament reading gives me an excuse to revisit Paradise Lost since, short though the reading is, it provides most of the material for Milton’s epic. The Genesis story seeks to explain consciousness–that which separates humans from animals–and also to account for the presence of evil in God’s beautiful creation. For Milton, the fruit is pride-driven knowledge, which causes us to view ourselves rather than God as the measure of the universe.

Here’s the original passage:

The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it. And the Lord God commanded the man, “You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die.”

Now the serpent was more crafty than any other wild animal that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, “Did God say, ‘You shall not eat from any tree in the garden’?” The woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees in the garden; but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree that is in the middle of the garden, nor shall you touch it, or you shall die.’“ But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate. Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves.

In Satan’s pitch to Eve, the ever-curious Milton reveals what it would take to tempt him. As with Doctor Faustus, upon whom the character is modeled, it involves reason, science and theology:

O sacred, wise, and wisdom-giving plant,

Mother of Science, now I feel thy power

Within me clear, not only to discern

Things in their causes, but to trace the ways

Of highest agents, deemed however wise.

Also like Faustus, subsequent action does not live up to this soaring rhetoric. Reason that is not rooted in God degenerates into casuistry, just as science that is not rooted in God spawns ungodly horrors. In the poem, Lucifer and Eve go on to use their unholy Reason to make intricate but fallacious arguments.

To use one’s Reason in a godly way would be to affirm the goodness of creation, not to elevate oneself above it. At one point, the Angel Raphael describes creation as “the Book of God” that has been given us to study:

Heaven

Is as the Book of God before thee set,

Wherein to read his wondrous works, and learn

His seasons, hours, or days, or months, or years…

Put another way, Milton would approve of the scientist whose aim is to appreciate the wonders of God’s creation but not the scientist who aims to set him/herself above them. As I read the poem, Milton is worried about those intellectuals that, like Richard Dawkins and Steven Hawking, become so puffed up with the power of scientific explanation that they confidently conclude that there is no God. In contrast to such arrogance, Raphael counsels for us to

be lowly wise:

Think only what concerns thee and thy being;

Dream not of other worlds, what creatures there

Live, in what state, condition or degree,

Contented that thus far hath been revealed

Not of Earth only but of highest Heaven.

In short, never lose sight of your own fallibility. The forbidden fruit is not knowledge itself—Milton himself loves to exercise his reason and is fascinated by science—but the desire to use knowledge for egotistical ends. Do not strive to “be as gods.”

In Milton’s view, the desire to become godlike arises from within the organs of our fancy or imagination. In Satan’s initial attempt to corrupt Eve, he whispers into her ear while she is asleep, causing her to lust after knowledge:

[H]im there they found

Squat like a toad, close at the ear of Eve;

Assaying by his devilish art to reach

The Organs of her Fancy, and with them forge

Illusions as he list, phantasms and dreams,

Or if, inspiring venom, he might taint

Th’ animal spirits that from pure blood arise…

When Eve tells Adam about her troubling dream, he provides a psychological explanation about how the mind is constructed. We need Reason, he says, to connect us to God. Otherwise, we will yield to Fancy’s wild images and desires. The process sounds like Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams:

But know that in the Soul

Are many lesser faculties that serve

Reason as chief; among these Fancy next

Her office holds; of all external things,

Which the five watchful Senses represent,

She forms Imaginations, eerie shapes,

Which Reason joining or disjoining, frames

All what we affirm or what deny, and call

Our knowledge or opinion; then retires

Into her private cell when Nature rests.

Oft in her absence mimic Fancy wakes

To imitate her; but misjoining shapes,

Wild work produces oft, and most in dreams,

Ill matching words and deeds long past or late.

Episcopalians, our rector sometimes tells us, do not leave their brains at the door. Adam, after hearing the Archangel Michael’s extensive history lesson and his account of Christ’s future sacrifice for humankind, is able to draw the correct lesson:

Henceforth I learn, that to obey is best,

And love with fear the only God, to walk

As in his presence, ever to observe

His providence, and on him sole depend,

Merciful over all his works, with good

Still overcoming evil, and by small

Accomplishing great things, by things deemed weak

Subverting worldly strong, and worldly wise

By simply meek; that suffering for Truth’s sake

Is fortitude to highest victory,

And to the faithful death the Gate of Life…

Michael confirms Adam’s observations and adds a few more. As he does so, he shows the emptiness of scientific knowledge without God:

This having learnt, thou hast attained the sum

Of wisdom; hope no higher, though all the stars

Thou knewst by name, and all th’ ethereal powers,

All secrets of the deep, all Nature’s works,

Or works of God in Heaven, Air, Earth, or Sea,

And all the riches of this World enjoyst,

And all the rule, one Empire; only add

Deeds to thy knowledge answerable, add Faith,

Add virtue, patience, temperance, add love,

By name to come called charity, the soul

Of all the rest: then wilt thou not be loath

To leave this Paradise, but shalt possess

A Paradise within thee, happier far.

Sin, then, is that within us that seeks to put ourselves above God’s creation. We all have this tendency. Thanks to Milton, we have a particularly vivid account of finding our way back to God after we have lost our way.

Further thought: I’d never realize until today how much Milton’s theory of fantasy draws on Midsummer Night’s Dream. Compare the following two passages:

She forms Imaginations, eerie shapes,

Which Reason joining or disjoining, frames

All what we affirm or what deny, and call

Our knowledge or opinion…

Here’s Theseus:

Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends.

And later:

Such tricks hath strong imagination,

That if it would but apprehend some joy,

It comprehends some bringer of that joy;

Or in the night, imagining some fear,

How easy is a bush supposed a bear!

Pragmatic Theseus, however, differentiates himself from lovers, poets and madmen whereas Milton would say that we all–including Theseus–are susceptible to the Satanic whisperings of the unconscious. That’s why promiscuity reigns supreme in Shakespeare’s green world.