Wednesday

Once again my friend Sue Schmidt has alerted me to a book about literature and life, this one about how literature helped save a life. In The Reading Cure: How Books Restored My Appetite, formerly anorexic Laura Freeman describes how books helped her to begin eating again.

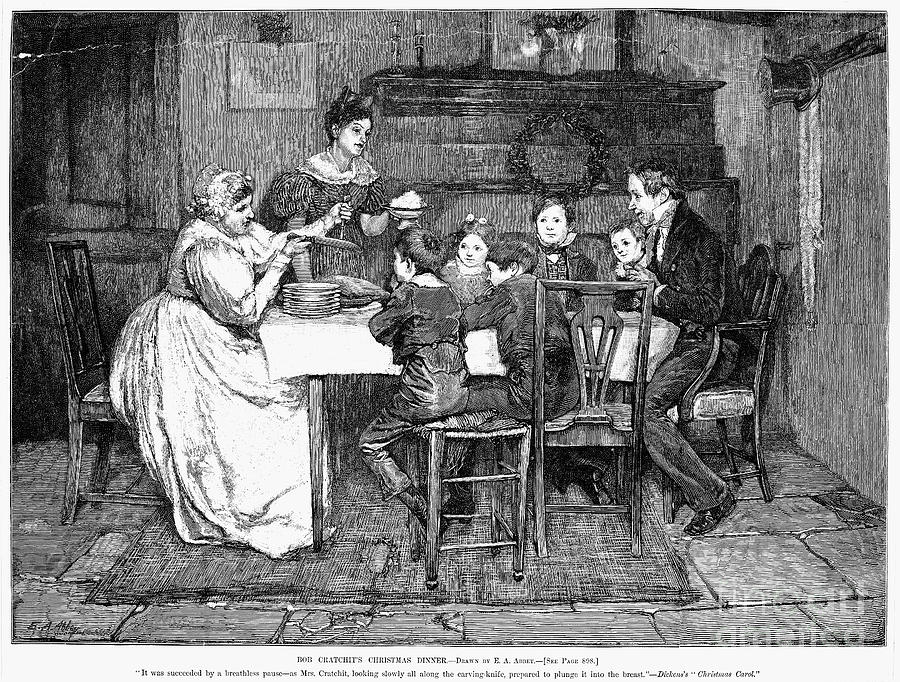

Many of the books were memoirs, but I focus here on the novels that she mentions. According to Guardian reviewer Sarah Hughes, Charles Dickens’s “lavish shared meals” helped her start thinking of food as an adventure. To put yourself in Freeman’s place, imagine how this passage from Christmas Carol might get you interested in eating again:

The poulterers’ shops were still half open, and the fruiterers’ were radiant in their glory. There were great, round, pot-bellied baskets of chestnuts, shaped like the waistcoats of jolly old gentlemen, lolling at the doors, and tumbling out into the street in their apoplectic opulence. There were ruddy, brown-faced, broad-girthed Spanish Onions, shining in the fatness of their growth like Spanish Friars, and winking from their shelves in wanton slyness at the girls as they went by, and glanced demurely at the hung-up mistletoe. There were pears and apples, clustered high in blooming pyramids; there were bunches of grapes, made, in the shopkeepers’ benevolence to dangle from conspicuous hooks, that people’s mouths might water gratis as they passed; there were piles of filberts, mossy and brown, recalling, in their fragrance, ancient walks among the woods, and pleasant shufflings ankle deep through withered leaves; there were Norfolk Biffins, squat and swarthy, setting off the yellow of the oranges and lemons, and, in the great compactness of their juicy persons, urgently entreating and beseeching to be carried home in paper bags and eaten after dinner. The very gold and silver fish, set forth among these choice fruits in a bowl, though members of a dull and stagnant-blooded race, appeared to know that there was something going on; and, to a fish, went gasping round and round their little world in slow and passionless excitement.

The Grocers’! oh, the Grocers’! nearly closed, with perhaps two shutters down, or one; but through those gaps such glimpses! It was not alone that the scales descending on the counter made a merry sound, or that the twine and roller parted company so briskly, or that the canisters were rattled up and down like juggling tricks, or even that the blended scents of tea and coffee were so grateful to the nose, or even that the raisins were so plentiful and rare, the almonds so extremely white, the sticks of cinnamon so long and straight, the other spices so delicious, the candied fruits so caked and spotted with molten sugar as to make the coldest lookers-on feel faint and subsequently bilious. Nor was it that the figs were moist and pulpy, or that the French plums blushed in modest tartness from their highly-decorated boxes, or that everything was good to eat and in its Christmas dress; but the customers were all so hurried and so eager in the hopeful promise of the day, that they tumbled up against each other at the door, crashing their wicker baskets wildly, and left their purchases upon the counter, and came running back to fetch them, and committed hundreds of the like mistakes, in the best humour possible; while the Grocer and his people were so frank and fresh that the polished hearts with which they fastened their aprons behind might have been their own, worn outside for general inspection, and for Christmas daws to peck at if they chose.

Not all food novels worked for Freeman. At first, one might think that a passage such as the following in Joanne Harris’s Chocolat would be enticing:

The air is hot and rich with the scent of chocolate. Quite unlike the white powdery chocolate I knew as a boy, this has a throaty richness like the perfumed beans from the coffee stall on the market, a redolence of amaretto and tiramisù, a smoky, burned flavor that enters my mouth somehow and makes it water. There is a silver jug of the stuff on the counter, from which a vapor rises. I recall that I have not breakfasted this morning.

Because Harris’s protagonist uses chocolate to rebel against a repressive Catholicism, however, Freeman says that the novel triggers the very anxieties she is trying to overcome. It makes sense that one who stopped eating because she was trying to become “smaller, quieter, less conspicuous” would shy away from Harris’s all-out battles between an indulgent chocolate store owner and a repressed village curate. Here’s Freeman describing her relationship with chocolate:

Chocolate is a strange, stubborn thing. It’s sold as a representation of ultimate sin and temptation, and unfortunately I think it’s rather knotted in my mind with all those ideas of badness and naughtiness. Like anyone, I have better days and worse days.

Dickens’s feasts, by contrast, come with less psychological baggage.

Freeman mentions one final novel that, while not about food, nevertheless played an important role in her recovery:

The unashamed gluttony of Laurie Lee may have altered her attitude to food – her description of a trip to Spain, during which she was finally able to try meals she would previously have rejected, are almost transcendent – but it was the advice of a very different author that lingered longest. “I really loved T.H. White’s The Once and Future King,” she says, “in particular, Merlin’s advice to his young apprentice, Wart, that when you’re low or sad, the thing that never fails, the thing you have absolute control of, is to teach yourself something, learn something new. It made me realize that when I am having a bad day – and they do come around – I can go to a museum, read a book, or go for a walk. I can fill my brain with something that isn’t my own nitty-gritty unhappiness.”

White’s novel is a quest narrative, and it sounds as though Freeman’s book is as well. As she tells the reviewer,

I think for people who have had anorexia or battled through depression there is a little undercurrent of it their whole lives. I hope that what my book is about is finding ways to be happy and love life. To make a future for yourself that isn’t bound by the various restrictions the illness puts on you.