Friday

The COVID-19 outbreak is providing America with a horrific new statistic to further dramatize America’s obscene wealth gap. Apparently African Americans have suffered well over 50% of the fatalities (75% in some localities)–which is to say the poor are experiencing the brunt of the epidemic. The lopsided numbers can be chalked up to unequal health care, a greater likelihood of preexisting conditions, crowded living arrangements, and the need to keep working, often on the front lines of the virus (as janitors, checkout clerks, mass transit drivers, sanitation workers, etc.). Social distancing is often a luxury available only to those with more money.

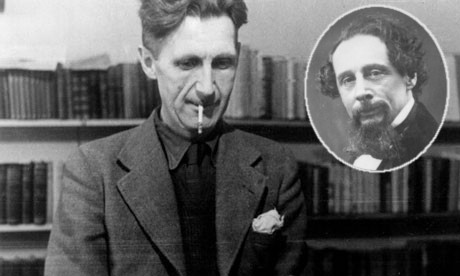

The virus may finally confront us with a reckoning that has been a long time coming, one where we may have to turn from Charles Dickens to George Orwell. So, at any rate, argues Janen Ganesh in a Financial Times article (thanks to reader Deepjeet Datta for the alert). Ganesh believes that looking to benevolent businesspeople like Dickens’s Fezziwig is a fool’s game. Only changing the very structure of the system will work.

Before quoting from the article, here’s Scrooge revisiting his old boss in the company of the Ghost of Christmas Past:

Old Fezziwig laid down his pen, and looked up at the clock, which pointed to the hour of seven. He rubbed his hands; adjusted his capacious waistcoat; laughed all over himself, from his shoes to his organ of benevolence; and called out in a comfortable, oily, rich, fat, jovial voice:

“Yo ho, there! Ebenezer! Dick!”

Scrooge’s former self, now grown a young man, came briskly in, accompanied by his fellow-’prentice.

“Dick Wilkins, to be sure!” said Scrooge to the Ghost. “Bless me, yes. There he is. He was very much attached to me, was Dick. Poor Dick! Dear, dear!”

“Yo ho, my boys!” said Fezziwig. “No more work to-night. Christmas Eve, Dick. Christmas, Ebenezer! Let’s have the shutters up,” cried old Fezziwig, with a sharp clap of his hands, “before a man can say Jack Robinson!”

I think also of Mr. Brownlow, the kind old philanthropist who saves Oliver Twist.

Neither Ganesh nor Orwell is impressed:

If only Murdstone were kinder to David Copperfield. If only all bosses were as nice as Fezziwig. That no one should have such awesome power over others in the first place goes unsaid by Dickens, and presumably unthought. And so his worldview, says Orwell, is “almost exclusively moral.” Dickens wants a “change of spirit rather than a change of structure.” He has no sense that a free market is “wrong as a system.” The French Revolution could have been averted had the Second Estate just “turned over a new leaf, like Scrooge.” And so we have “that recurrent Dickens figure, the Good Rich Man”, whose arbitrary might is used to help out the odd grateful urchin or debtor. What we do not have is the Good Trade Unionist pushing for structural change. What we do not have is the Good Finance Minister redistributing wealth. There is something feudal about Dickens. The rich man in his castle should be nicer to the poor man at his gate, but each is in his rightful station.

Dickens, in fact, is outrightly hostile to trade unionists in Hard Times where, in a strange twist, he lumps them together with the tyrannical factory boss. The good worker Joe, who declines to fight for his rights and whose only reward for a wretched life comes to him in heaven, is shunned by both. Civil Rights activists used to characterize this vision as “pie in the sky by and by.” Ganesh points to the myopia at work:

You need not share Orwell’s ascetic socialism to see his point. And to see that it applies just as much to today’s economy. Some companies are open to any and all options to serve the general good — except higher taxes and regulation. “I feel like I’m at a firefighters’ conference,” said the writer Rutger Bregman, at a Davos event about inequality that did not mention tax. “And no one is allowed to speak about water.”

Orwell, then, is the author we should be looking to:

What Orwell would hate about Stakeholder Capitalism is not just that it might achieve patchier results than the universal state. It is not even that it accords the powerful yet more power — at times, as we are seeing, over life and death. Under-resourced governments counting on private whim for basic things: it is a spectacle that should both warm the heart and utterly chill it. No, what Orwell would resent, I think, is the unearned smugness. The halo of “conscience”, when more systemic answers are available via government. The halo that Dickens still wears. You can see it in the world of philanthropy summits and impact investment funds. The double-anniversary of England’s most famous writers since Shakespeare… serve as a neat contrast of worldviews. Dickens would look at the crisis and shame the corporates who fail to tap into their inner Fezziwig. Orwell would wonder how on earth it is left to their caprice in the first place. The difference matters because, when all this is over, there is likely to be a new social contract. The mystery is whether it will be more Dickensian (in the best sense) or Orwellian (also in the best sense). That is, will it pressure the rich to give more to the commons or will it absolutely oblige them?

Our most ambitious Dickensian philanthropists would be those using their money to fight disease (Bill Gates), the spread of guns (Michael Bloomberg), autocratic systems (George Souros), and climate change (Tom Steyer). But billionaires are even more likely to use their money to rig the system and get special favors. In my state of Tennessee, the rightwing Koch brothers pressured the legislature not to accept Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion, and the misery resulting from this single act outweighs much of the good done by Bloomberg or Steyer. So I agree with Ganesh that Dickens is of little use here.

Or rather, he provides an important service in dramatizing the plight of the poor. For policy answers, however, politicians who can figure out ways to enact policy based on Orwell’s insights are likely to do far more good.

Further thought: The author who may do the best job at exposing Dickens’s vision, at least artistically, is Bertolt Brecht. In a play like The Good Woman of Setzuan, he shows how a wealthy individual’s good deeds cannot address systemic inequality. In fact, when the press of people’s needs threatens to swamp newly wealthy Shen Teh, a prostitute with a heart of gold, she must invent a ruthless capitalist dark double, Shui Ta, in order to stay afloat. Only a generalized distribution of wealth would address the society’s problems.