Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Thursday

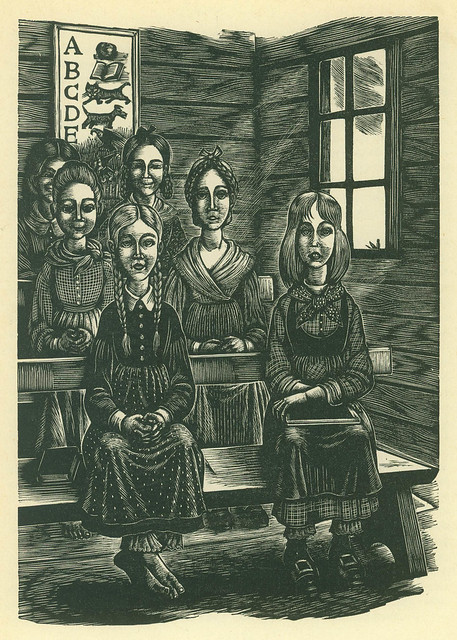

This being Teacher Appreciation Week, I share the classroom experiences of one of literature’s great teacher characters. In Jane Eyre we see a true professional at work.

Commenting on the Lilliputian system of education, Jonathan Swift observes “that parents are the last of all others to be trusted with the education of their own children.” Why certain parents think they can do a better job than skilled professionals says more about them than about our education system. These parents remind me of Blanche Ingram and her sisters who, right in front of Jane, show how badly they treated the governesses who taught them. We are fortunate that, even when suffering similar disrespect, our underpaid and overworked teachers demonstrate the same commitment to their students that Jane does.

I’ll admit that bad teachers exist, and in Bronte’s novel we get an instance of one in Lowood School’s Miss Scatcherd, who publicly humiliates the angelic Helen Burns and condemns her “to a dinner of bread and water on the morrow because she had blotted an exercise in copying it out.” Scatcherd, by failing to appreciate Helen’s beautiful mind, prompts Jane to reflect, “Such is the imperfect nature of man! such spots are there on the disc of the clearest planet; and eyes like Miss Scatcherd’s can only see those minute defects, and are blind to the full brightness of the orb.”

So yes, there are those who focus on defects rather than seeing the full student.

But there are more Jane Eyres and Miss Temples than Scatcherds in our school systems. Temple, the principle of Lowood, knows how to be teacher that both Jane and Helen need in their hours of extremity. Fair, kind, empathetic and just, Temple becomes a model for Jane. We go on to see Jane in three teaching situations: at Lowood when she grows up, at Thornfield Hall as governess to Adele, and in a country school as sole teacher.

While Jane has some nationalist prejudices when it comes to Adele (she regards her as a French coquette), she nevertheless takes her teaching duties seriously and the results are good. We know this from an interchange with Rochester regarding Adele’s progress. He has brought his ward a gift (“un cadeau”) and wonders if Jane expects one as well:

“I have examined Adèle, and find you have taken great pains with her: she is not bright, she has no talents; yet in a short time she has made much improvement.”

“Sir, you have now given me my ‘cadeau;’ I am obliged to you: it is the mead teachers most covet—praise of their pupils’ progress.”

When Jane is put in charge of a country schoolroom, she shines yet brighter, even though her task is a daunting one. She describes her situation:

This morning, the village school opened. I had twenty scholars. But three of the number can read: none write or cipher. Several knit, and a few sew a little. They speak with the broadest accent of the district. At present, they and I have a difficulty in understanding each other’s language. Some of them are unmannered, rough, intractable, as well as ignorant…

She adds that others, however, “are docile, have a wish to learn, and evince a disposition that pleases me.” And she reminds herself of a truth that every good teacher knows:

I must not forget that these coarsely clad little peasants are of flesh and blood as good as the scions of gentlest genealogy; and that the germs of native excellence, refinement, intelligence, kind feeling, are as likely to exist in their hearts as in those of the best-born. My duty will be to develop these germs: surely I shall find some happiness in discharging that office.

Jane doesn’t pretend that this is her first choice of occupation. “Much enjoyment I do not expect in the life opening before me,” she admits. After all, she was on the verge of marrying the master of Thornfield Hall. But she resolves to soldier on, reassuring herself that “if I regulate my mind, and exert my powers as I ought, [this will] yield me enough to live on from day to day.”

The teaching episodes, often skipped over in film and television adaptations of Jane Eyre, are critical to her developing a full sense of self. After all, when she was first on the verge of becoming Mrs. Rochester, she all but gave away her power, allowing Rochester to shape her. As she puts it at one point,

My future husband was becoming to me my whole world; and more than the world: almost my hope of heaven. He stood between me and every thought of religion, as an eclipse intervenes between man and the broad sun. I could not, in those days, see God for His creature: of whom I had made an idol.

She leaves because “I care for myself,” and this care involves escaping his influence. Her teaching stint helps her step into her powers, all the more so because challenges her to the max. Sounding like many first-year teachers, the task ahead of her at first seems hopeless:

I continued the labors of the village-school as actively and faithfully as I could. It was truly hard work at first. Some time elapsed before, with all my efforts, I could comprehend my scholars and their nature. Wholly untaught, with faculties quite torpid, they seemed to me hopelessly dull; and, at first sight, all dull alike…

Once education begins to work its wonders, however, she discovers she has underestimated her students. There’s more in them than she first realized:

There was a difference amongst them as amongst the educated; and when I got to know them, and they me, this difference rapidly developed itself. Their amazement at me, my language, my rules, and ways, once subsided, I found some of these heavy-looking, gaping rustics wake up into sharp-witted girls enough. Many showed themselves obliging, and amiable too; and I discovered amongst them not a few examples of natural politeness, and innate self-respect, as well as of excellent capacity, that won both my goodwill and my admiration.

The students respond to her appreciation:

These soon took a pleasure in doing their work well, in keeping their persons neat, in learning their tasks regularly, in acquiring quiet and orderly manners. The rapidity of their progress, in some instances, was even surprising; and an honest and happy pride I took in it: besides, I began personally to like some of the best girls; and they liked me. I had amongst my scholars several farmers’ daughters: young women grown, almost. These could already read, write, and sew; and to them I taught the elements of grammar, geography, history, and the finer kinds of needlework. I found estimable characters amongst them—characters desirous of information and disposed for improvement—with whom I passed many a pleasant evening hour in their own homes.

To be sure, Jane’s teaching career proves to be of short duration, and eventually she returns to Thornfield to nurse Rochester back to health and become his wife (“Reader, I married him”). Some find this ending dissatisfying.

For instance, in her study of the marriage plot, feminist Rachel Blau DuPlessis complains how, in the 19th century, women were not allowed their own growth novels: they either ended up married or dead. Even in Jane Eyre, she says, whatever growth occurs in the middle of the novel is held of no account by the end as the “hero” dwindles to a married heroine.

To her credit, Bronte changes this in her next novel (spoiler alert). In what looks, until the last pages, like a romance, Villette concludes with Paul Emanuel dying at sea and Lucy Snowe running her own school. Readers, including Bronte’s own father, complained vociferously, causing Bronte to alter the ending—but instead of giving them what they wanted, she shrouded the ending in ambiguity, telling them that it was up to them, not to her, to imagine a “Reader I married him.” Or as she puts it, ”Let them picture union and a happy succeeding life.”

Who needs to be a wife when one can be a teacher?