I share today another section from Does Literature Make Us Better People? A 2500-Year-Old Debate, a book project currently undergoing revision. In the previous chapter I look at what Marx and Engels say about literature’s impact on people’s lives. In this chapter I look at Freud and Jung’s thoughts. Here’s what I say about Freud. Any feedback is welcome.

If Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud are sometimes paired in the history of thought, it is because Marx sees unseen forces moving the course of history and Freud sees unseen forces moving the lives of individuals. If literature helps us understand these foundational forces, then it does indeed have the potential to change lives. It’s just that where literary Marxists see literature making lives better in the aggregate, literary Freudians and Jungians see it doing so one person at a time.

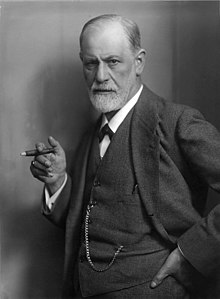

Freud (1856-1939) was a Jewish psychologist practicing in Vienna. After receiving medical training at the University of Vienna and the Vienna General Hospital, Freud went into private practice, where he stumbled on “the talking cure” when his severely neurotic patient Anna O discovered that her symptoms were reduced when she recalled and recounted traumatic incidents from her childhood.

Other of Freud’s theories include the damage inflicted by repression, the dynamics of patient transference (from the love object to the analyst), the significance of dreams and (controversially) the existence of a subliminal death wish. Freud attracted a set of noteworthy followers, who spread the word about psychoanalysis, although some would evolve away from him and set up other schools. He spent his final years in London, having left Vienna to escape the Nazis.

Although he is considered the founder of psychoanalysis, Freud today is often taken more seriously by the literary community than by fellow psychologists. Some of the latter regard him more as a poet than a scientist—this is not a compliment—and it is true that he attributes many of his discoveries to the literature he encountered growing up, especially Shakespeare and the great Greek tragedians.

Psychoanalysis, in the words of Freudian psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, “was created to enable man to accept the problematic nature of life without being defeated by it, or giving in to escapism.” Works of art enter into the process, meanwhile, both by articulating our problems and by helping us achieve (in the words of sociologist and cultural critic Philip Rieff) “emotional stability” and “self-mastery.” Literature does this at two levels of engagement. Simply reading poems and stories and attending plays (in other words, immersing without significant reflection) takes us into and through debilitating inner conflicts. Literature delights us because we feel we can control psychological challenges.

On a more conscious level, however, when we analyze literature from a Freudian point of view, we come to better understand these conflicts and see our options. Furthermore, by studying our psychological responses to various works, we can diagnose what ails us. Literature, at this point, becomes instructive.

Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex is a good place to begin a discussion of Freud, in part because it allows us to further explore the study of audience response initiated by Aristotle, in part because we can see how Freud uses the play to formulate a number of his major ideas.

We have already noted that Aristotle attributes the intense emotional responses generated by Oedipus to pity and fear. We speculated that, for Athenian audiences, the intense emotions arose from identifying with characters who (consistent with Athenian optimism) thought they could control their destinies, only to discover that certain aspects of existence were beyond them. Freud, while fascinated by the intense emotions evoked by Oedipus and interested in Aristotle’s pity-fear dynamic, has a different explanation for why the play would have evoked such intense emotions.

For him, Oedipus articulates desires so socially taboo that we can’t even acknowledge we have them. The male child, who doesn’t think in nuance, desires to kill that father, who is usurping his rightful place as the center of his mother’s attention. Because the father is so powerful, however, the child imagines being punished for his murderous wishes, perhaps by castration. For self-protection, therefore, the child represses them, and what we repress becomes toxic. Freud may or may not have said, when asked to describe his theories, “secrets make us sick,” but in any event the formulation functions as a useful summation. Taboos have such a hold on our mind that we can feel nauseated at the mere mention of them, and when Oedipus discovers that he has actually acted them out, he symbolically castrates himself, poking out his eyes with Jocasta’s brooch to override the mental pain.

Therefore, when Greek audiences watched him slowly but inexorably learn that he has acted upon taboo desires, they would have been both horrified and relieved at seeing these desires expressed. They acknowledged the desires through identification (pity) and distanced themselves through denial (fear). In sum, they felt cathartic relief at the realization that they could approach and survive that which they dared not name. While Plato doesn’t specifically mention Oedipus in The Republic—the literary scenes he mentions are Hesiod’s misbehaving deities and Odysseus’s encounters with Hades and with food—one can see why he doesn’t want the great tragedians in his rational utopia. The emotional dynamite with which Sophocles is playing exceeds the capacity of philosopher guardians.

Without literature, however, society cannot achieve psychic health, which is why Aristotle lauds the emotional effects of catharsis. Renaissance playwright Christopher Marlow provides us a great example of this with his Doctor Faustus, who uses Homer and the lyre musician Amphion (from Greek mythology) as anti-depressants and suicide prevention treatment. Faustus is finding himself torn between his desires and religion’s strictures when he speaks of poetry’s benefits:

My heart’s so harden’d, I cannot repent:

Scarce can I name salvation, faith, or heaven,

But fearful echoes thunder in mine ears,

“Faustus, thou art damn’d!” then swords, and knives,

Poison, guns, halters, and envenom’d steel

Are laid before me to dispatch myself;

And long ere this I should have slain myself,

Had not sweet pleasure conquer’d deep despair.

Have not I made blind Homer sing to me

Of Alexander’s love and Oenon’s death?

And hath not he, that built the walls of Thebes

With ravishing sound of his melodious harp,

Made music with my Mephistophilis?

Why should I die, then, or basely despair?

For Freud, repressing our socially forbidden desires takes such a mental toll that we must figure out ways to manage the situation. One way is through sublimation, in which we find a lofty substitute. Art fulfills this function so that, to take a famous literary example, the tormented protagonist in Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice transmutes his unacceptable desire for an adolescent boy into poetry. When we read such works, rather than allowing ourselves to be pulled down by our guilt, we feel ennobled by our suffering.

Our dreams also come to our rescue. While our forbidden desires do damage when we push them into our subconscious, our dreams provide an outlet, transforming our mental distress into fictional narrative, poetic images, and dramatic enactments. That’s not the end of the process, however. Because, even when asleep, we still regard our desires as dangerous and unacceptable, our dreams disguise them. If we are to identity what troubles us, therefore, we must interpret them, and in Interpretation of Dreams, Freud contrasts the actual or “latent” content of our dreams with their surface or “manifest” content. He also tracks the dreamwork process, explaining why dreams take the shape that they do. According to Carl Jung, Freud had a remarkable ability to help patients interpret their dreams, an important step in lessening the effects of toxic repression.

Jocasta is partially right, partially wrong when, in response to Oedipus’s fears, she tells him, “Do not worry you will wed your mother. It’s true that in their dreams a lot of men have slept with their own mothers, but someone who ignores all this bears life more easily.” She is right that the incest wish is the stuff of dreams (although Freud would say it is usually disguised) but wrong that such desires can be ignored. Repressed, they return as neurosis, which in the play is symbolized by the plague that has broken out in Thebes. Only by facing up to the dark desires can we keep them from tearing us apart. Sophocles captures this in the sequel to Oedipus that he wrote at the end of his life, Oedipus at Colonus. Oedipus may be overwhelmed by self-horror at the end of the first play, but by the end of the sequel he has achieved spiritual mastery.

Literature has a special relationship to dreaming. As Rieff puts it, a work of art, like a dream, works in part as “a safety valve, a form of exhibitionism, in which the tension accumulated by private motives is drained off in public display.” That being said, a work of art is also different than a dream, in ways which Freud lays out in his essay “Creative Writers and Day Dreaming.”

As the title indicates, Freud describes imaginative writing as a form of conscious dreaming. In other words, creative authors tap into the same repressed desires that lead to dreams, only in this case they can consciously shape the dream material. As Freud describes the process in his essay on “The Uncanny,”

In the main we adopt an unvarying passive attitude towards real experience and are subject to the influence of our physical environment. But the storyteller has a peculiarly directive influence over us; by means of the moods he can put us into, he is able to guide the current of our emotions, to dam it up in one direction and make it flow in another.

The author achieves a certain mastery over emotional turbulence by composing the work and audiences achieve that inner mastery by reading it.

Freud spells out some of the turbulence in his daydreaming essay. Look carefully at stories, he says, and you will see them dealing with sides of ourselves that shame us: ambition phantasies for men, love phantasies for women. Repression has entered in because (at least at the time Freud was writing)

the well-brought up young woman is only allowed a minimum of erotic desire, and the young man has to learn to suppress the excess of self-regard which he brings with him from the spoilt days of his childhood, so he may find his place in a society which is full of other individuals making equally strong demands.

Although such phantasies are to be found in all literature, Freud says they are particularly evident in what Freud kindly calls works by “less pretentious authors.” Today we may refer the genres as “chick lit” and “dick lit.” Literature, like dreams, disguises these shameful desires so that readers can approach them without revulsion or shame, thereby robbing them of their toxic power and allowing us to achieve stability and mastery. Sounding like Plato, who regards poets as “deceivers” who trick us through beauty, Freud says writers “bribe” us with formal technique: they soften “the character of [our] egoistic daydreams by altering and disguising it.” This allows us “to enjoy our own day-dreams without self-reproach or shame,” thereby liberating the “tensions in our minds.” This release, as Freud sees it, is one of a novel’s chief pleasures.

It sounds as though Freud’s only distinction between greater and lesser literature is that great writers bribe us better. If so, I would disagree: as I argue in the feminism and Jane Austen chapters, great literature serves us better psychologically than “less pretentious” potboilers because one is far better off if one reads substantive treatments of underlying anxieties (such as, say, Sophocles’s Oedipus). One may get momentary tension relief from reading about the girl getting the guy or the guy getting the bad guys, but that’s it. The work you put into a great work returns dividends in the form of better understanding your state of mind. In short, you get the literary therapy you pay for.

I conclude my summation of Freud with a quick glance at literature’s therapeutic process as it occurs in two genres. People generally read fairy tales and horror fiction without looking for deeper meaning, which gives us the opportunity to look at the benefits literature bestows (from a Freudian point of view) at both the pre-reflective and reflective levels.

In The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, prominent Freudian psychologist Bruno Bettelheimtalks about how children need folk fairy tales to find meaning in their confusing lives:

Just because his life is often bewildering to him, the child needs even more to be given the chance to understand himself in this complex world with which he must learn to cope. To be able to do so, the child must be helped to make some coherent sense out of the turmoil of his feelings. He needs ideas on how to bring his inner house into order, and on that basis be able to create order in his life. He needs…a moral education which subtly, and by implication only, conveys to him the advantages of moral behavior, not through abstract ethical concepts but through that which seems tangibly right and therefore meaningful to him.

Folk fairy tales, Bettelheim says, confront children with basic human predicaments—maturation, conflict, aging, death, the limits of our existence—respecting them for their anxieties and reassuring them that they can achieve satisfactory resolutions. Different fairy tales specialize in different anxieties, as a quick glance indicates. In “Hansel and Gretel,” for instance, children replay (among other things) abandonment fears; in “Snow White,” conflict with the mother; in “Jack and the Beanstalk,” conflict with the father; in “Cinderella,” sibling rivalry; in “Little Red Cap,” anxieties about growing up; in “Sleeping Beauty,” turbulent adolescence. The child instinctively recognizes that these stories speak to primal concerns, providing images and a language for what otherwise would feel like murky chaos.

“Hansel and Gretel,” for instance, sees the panicked children, confronted with adult problems, reverting to an infantile state, so that they gorge themselves on the gingerbread house. In the witch’s cannibalism, however, they come to recognize “the danger of unrestrained oral greed and dependence.” To survive, they must develop initiative and realize that their only resource lies in intelligent planning and acting. They must exchange subservience to the pressures of the id for acting in accordance with the ego.” By the end of the story, they have acquired new treasures: “new-won independence in thought and action, a new self-reliance which is opposite of the passive dependence which characterized them when they were deserted in the woods.” Bettelheim conducts similar analysis of the other fairy tales he mentions.

Freud’s essay on the uncanny (a.k.a. the spooky) is particularly useful to understanding why we often find ourselves simultaneously repulsed by and attracted to the works of E.T.A. Hoffman, Edgar Allan Poe, H.P. Lovecraft, Stephen King, and other masters of gothic horror. It’s because we sense something recognizable in the monsters. “We have met the enemy and he is us,” Pogo cartoonist Walt Kelly once wrote, riffing off an Admiral Perry quote, and Marlow in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness talks of “the fascination of the abomination.” The energy we put into denying our commonality comes back to us in feelings of dread, what Freud calls “the return of the repressed”: the more we deny, the greater the horror. We see this dynamic played out in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde where Jekyll does all he can to deny his hidden Hyde self, which is at odds with his sense of himself as a civilized gentleman. Jekyll uses strong drugs to suppress the self he “hides,” but as a result Hyde only grows in power, trampling on children and clubbing people to death. Reading such fiction allows us to approach, acknowledge, and thereby defuse our guilt and shame over our unsavory selves.

All this occurs at the pre-reflective level. Once we understand the process, however—once we begin applying Freud’s tools to understand why we respond as we do—we open up new windows into the psyche, both our own and those of others. Watching a child responding to a favorite fairy tale gives us a better grasp of his or her fears. With horror, meanwhile, we can probe the literary monster that we find the most frightening because this one will give us the deepest understanding of our own anxieties. If we interpret our responses to literature as Freud interprets dreams, we can achieve at least a modicum of self-knowledge and self-mastery.