Wednesday

New Yorker writer Francisco Cantu has alerted me to an important book on the role that the frontier plays in the American imagination. Greg Gandin’s The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America, traces Donald Trump’s wall back to America’s frontier days. I describe the article here because it mentions two novels and a poem.

The frontier/border debate resembles the immigration debate in America’s identity struggle. Just as there are those who welcome diversity and those who want to shut it out, so there are those who see the frontier as an expansion of human possibility and those who regard as an opportunity to dominate and subdue. Grandin’s goal, Cantu says, is

to reposition race-based violence to the center of the frontier narrative, exposing it as foundational to today’s “border brutalism.”

Cantu is familiar with this brutalism, having served for a while as a border patrol agent. He has witnessed how members of ICE dehumanize and are dehumanized in turn.

Among the incidents described by End of Myth is one where Arkansas soldiers

descended upon a group of Mexican war refugees in a cave, raping and slaughtering victims as they pleaded for mercy. Many of these rabid Army volunteers, Grandin notes, were former bounty hunters with an unchecked thirst for scalping their victims.

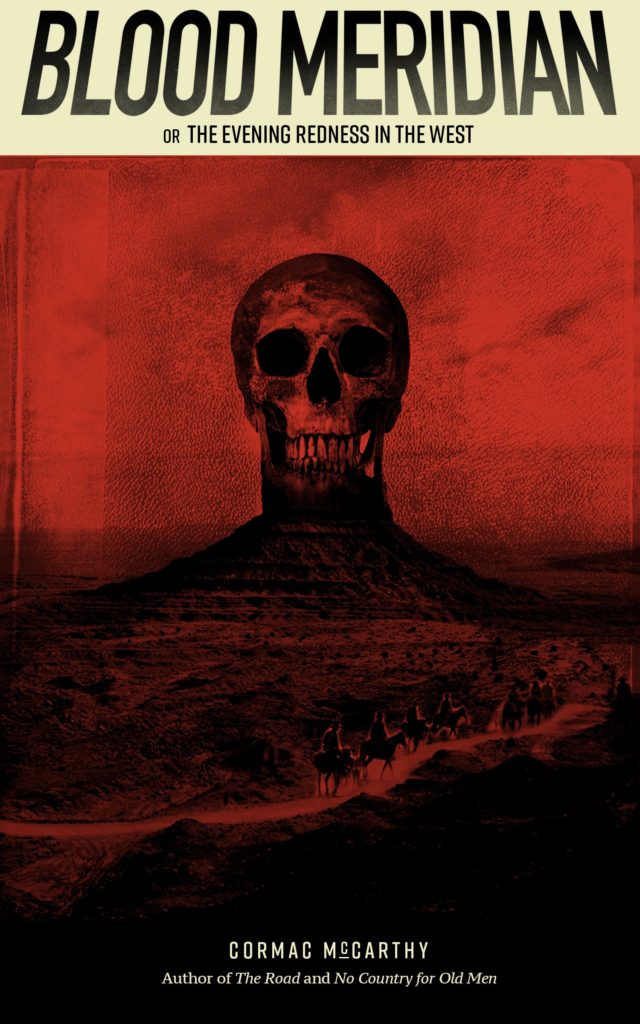

Two novels treat this history. One is Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian (1985), often seen as his masterpiece. Judge Holden is an eloquent psychopath whose violence knows no bounds and who declares,

It makes no difference what men think of war. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.

By the end of the novel, the Judge reigns supreme, somewhat like Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men (if you’ve seen the film). Grandin draws from Blood Meridian to depict “the violence perpetrated by remorseless white American men, unconcerned with the traumas they were unleashing into history.”

Cantu also mentions a counter narrative that, while acknowledging the violence, shows us a principled protest as well. From Cantu’s description, it sounds like Hernan Diaz’s In the Distance (2017) has a Dances with Wolves aspect:

Set in the same historical period [as Blood Meridian], the novel depicts a young immigrant who has become separated from his brother on the docks in Europe. He accidentally boards a ship to San Francisco, while his brother, it is presumed, arrives in New York. And so our stoic protagonist sets out eastward across frontier America, crossing the country in reverse, against an advancing tide of settlers, explorers, and outlaws. As expected, he is engulfed by hardship, drama, and violence, but, when he finds himself in the middle of a McCarthyesque slaughter of Native Americans, he is unable to soldier on like the hardened men of so many Westerns. Instead, he retreats into the wilderness, where he hopes no human will ever find him, and burrows deep into the ground. But, even in his attempt to escape the violence of which he has become a part, the men he has killed stare at him in his dreams, and the rare utterances of his own voice sound monstrous.

Both novels bring home the point that Trump is tapping into a deep strain of American racism as he calls for his wall. Grandin notes that “the point isn’t to actually build ‘the wall’ but to constantly announce the building of the wall.”

Cantu concludes his review with a story that gets at the spiritual damage caused by walls and wall rhetoric. Ofelia Rivas, a Tohono O’odham elder, describes what happened when, following 9-11, new border barriers disrupted traditional pilgrimage routes:

The year the barriers went up, Rivas says, “we lost eleven elders. One after another, they passed away. It just seemed they couldn’t comprehend what was happening.” It was as if they had been poisoned, as if America had found a new way to take their land.

To set up the impact on Rivas herself, Cantu references “Long Hair,” by O’odham poet Ofelia Zepeda:

On the other side they sing and dance in celebration.

When we get there our hair must be long so that they recognize us.

Our hair is our dress.

It is our adornment.

We make sure it is long so they recognize us.

Cantu writes,

When the walls went up, Rivas remembers, she had long hair. Each time an elder died, however, she would cut a length of it as an act of homage. “By the end of the year,” she recalls, “my hair was gone.”

When House Speaker Nancy Pelosi calls the wall “immoral,” she may not have the Tohono O’odham in mind, but she recognizes dark energy when she sees it.