In the weeks following my son Justin’s death, after the funeral and the memorial service and the departure of friends and relatives, I retreated into my study (it was summer vacation). I had to do something so I returned to a book I had begun writing on “how classic British literature can change your life.” Over the summer, I worked on my chapters on Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. I found both speaking to my grief in deep ways.

In the weeks following my son Justin’s death, after the funeral and the memorial service and the departure of friends and relatives, I retreated into my study (it was summer vacation). I had to do something so I returned to a book I had begun writing on “how classic British literature can change your life.” Over the summer, I worked on my chapters on Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. I found both speaking to my grief in deep ways.

I will write another time about how Beowulf came to my rescue, although you will get a glimpse of the role it played if you read my blog entries of the week of April 27, 2009, which focus on Grendel’s mother and the dragon. This week is devoted to Sir Gawain.

Sir Gawain, I came to see it, is about the inevitability of death and the insistence of life. Although it is an ironclad fact that we and those we love will one day die, we push this knowledge to the back of our minds and usually act as though we will live forever. Too often we take life for granted and fail to appreciate or take advantage of its wonders. We become distracted by trivialities and spend an inordinate amount of time fretting over small stuff.

The Green Knight pushing his way into the Camelot merrymaking was like Justin’s death pushing its way into my life. Everything had to stop. Of course, in the poem it is Gawain learning that he only has a year to live and journeying to meet his death, whereas with me, my journey was to figure out how to handle a death that had already happened. But in both of our cases, we were wrestling with the meaning of death—and of life too because they can’t be separated. The poem helped me see my mourning as a quest. I would ride through the dark forest and beat at the doors of this dark and terrible mystery, demanding that it offer up an explanation.

There was some consolation to thinking of myself involved in a quest. Better that than thrashing around frantically in stunned incomprehension, something like (as I imagined it) Justin thrashing around in frenzied panic in the cold waters. Thinking of myself as a knight embarking on a disciplined quest helped counteract those moments when I yielded to bouts of black depression or icy numbness. It put a frame around my searching.

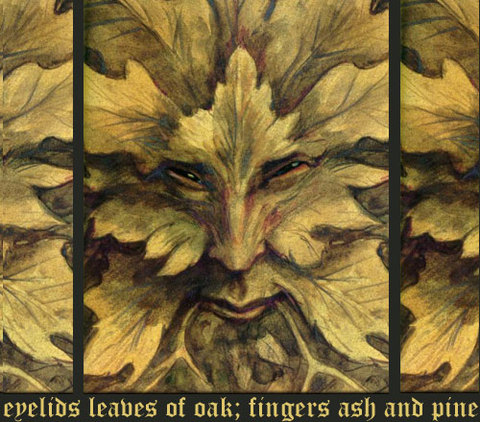

Gawain thinks that he can shrug off death and simply continue his normal knightly activities. I have come to see that as a form of denial. I have also come to see denial as not entirely bad, a way of protecting ourselves. But denial lasts only so long and it can also prevent us from acknowledging when we are deeply depressed. I think Gawain is depressed. The poem doesn’t tell us outright this because it is not a psychologically introspective work. But the signs are there: Gawain, as I see it, is riding into the dark forest of his mind, and life suddenly seems to be drained of color. He is fighting knightly battles, but they come at him in such an unending succession that the poet doesn’t even see fit to describe them. The forest, meanwhile, proceeds to become darker and colder. By the end, it is impossibly old and mysterious:

By a mountain next morning he makes his way

Into a forest fastness fearsome and wild;

High hills on either hand, with hoar woods below,

Oaks old and huge by the hundred together.

The hazel and the hawthorn were all intertwined

With rough raveled moss, that raggedly hung,

With many birds unblithe upon bare twigs

That peeped most piteously for pain of the cold . . .

I recognized myself in Gawain lost in that ancient forest, and I recognized myself in the bird peeping in self-pity for pain of the cold. Mere force of will could keep neither of us going. Sometimes it is not until we are at such extremity that we are willing to abandon our insistence on self-sufficiency and reach beyond ourselves in search of answers. In Gawain’s case, he prays to Christ and to Mary. My case was not quite so dramatic, although I too had been praying—but I too got that I couldn’t dictate any answers that the universe had for me. I would have to open myself to receive them.

The answer Gawain gets is the castle. I have come to see the wisdom that this castle contains. Our lives are ruled over by the Bertilaks, he the Lord of Death, she the Lady of Life. He is hunter of all that lives and, as we see in his hunts, he always gets his quarry, with the death of the animals presented in graphic detail. She, meanwhile, is the vibrancy of life: sensual, sexual, inviting. The challenge that the castle of life and death offers world weary travelers is this: if we could fully accept, in all their material finality, our deaths and the deaths of those we love, then we could also open ourselves fully to our lives.

Opening ourselves fully to life would involve stepping so completely into its sensual immediacy that, when death finally came, we would have no sense of having misspent a gift. It would mean that we would spend that extra time with our children, just as I spent three hours that were meant to be devoted to paper grading instead talking to Justin in our final conversation. It would mean, as Tennyson writes in his poem “Ulysses,” drinking life to the leas. That’s the challenge that Gawain is presented with, and it was the insight that I was getting as I read the poem in the weeks following Justin’s death.

I will continue talking about our castles of life and death in tomorrow’s entry.

2 Trackbacks

[…] remember feeling something like this after my son Justin died. In a previous series of posts (here’s the first one) I have described looking out at the forest that borders our backyard and being amazed at how life […]

[…] Gawain’s Castle of Life and Death […]