Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

For my weekly report on Angus Fletcher’s Wonderworks: The 25 Most Powerful Inventions in Literature, I’m featuring one of his more dubious ideas. But since it highlights one of my favorite passages in literature, which appears in one of my favorite novels, I can at the very least thank Fletcher from getting me to think about them in new ways.

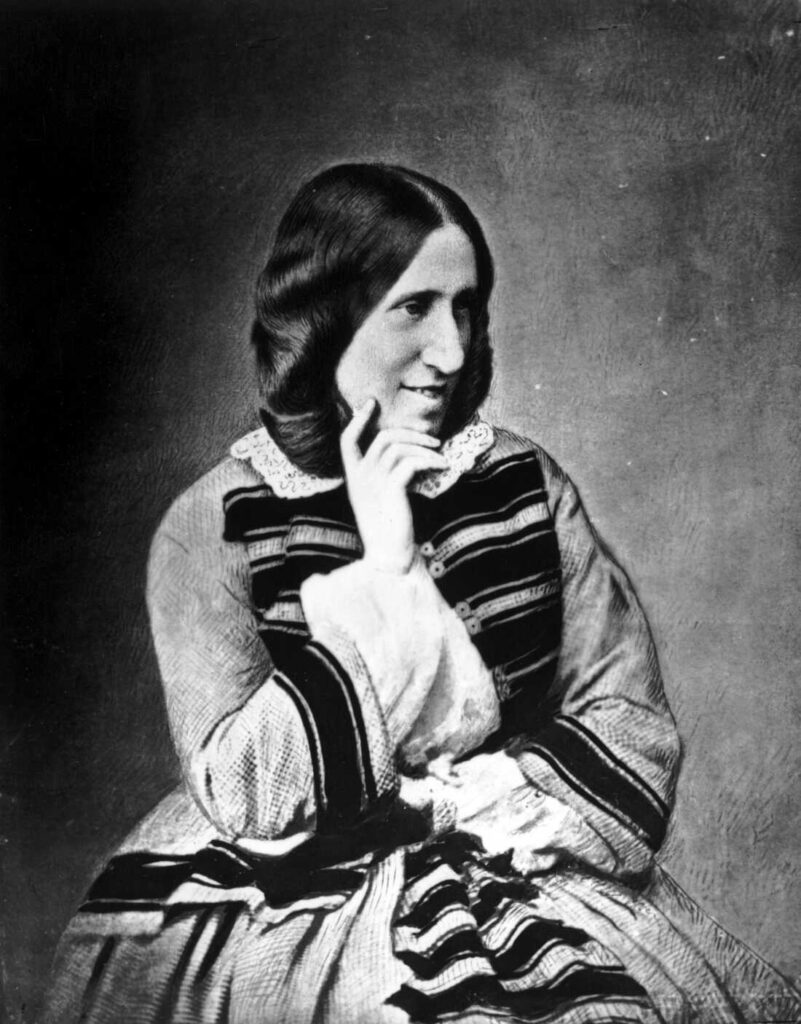

The work is George Eliot’s Middlemarch, which Fletcher claims helped develop the idea of secular humanism. The invention is the author’s use of “you and me,” which we see surface in chapter 73 and again in the famous final passage, which is the one that ranks so high with me. In the earlier passage, Eliot writes,

Pity the laden one; this wandering woe

May visit you and me.

It’s a sentiment we encounter in the Phil Ochs/Joan Baez song, “There but for fortune.”

To appreciate the final passage in Middlemarch, it’s first useful to know a little about the plot. There are a number of very sympathetic characters who want to do good in the world and whose efforts fall far short of their desires. One of these is Dorothea Brook, one of my favorite characters in all of literature, who thinks she is marrying a Milton but instead finds her husband to be a stuffy academic. So instead of assisting to bring a great work into the world, she finds herself cooped up in a loveless marriage. In her final summation of Dorothea’s life, Eliot writes,

Certainly those determining acts of her life were not ideally beautiful. They were the mixed result of young and noble impulse struggling amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state, in which great feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion. For there is no creature whose inward being is so strong that it is not greatly determined by what lies outside it….

Eliot goes on to say that, although Dorothea ended up in quiet channels rather than in a famous river, she still had a significant impact on the lives she came into contact with. In fact, the world is a better place because it has Dorotheas in it, even though they live hidden lives and go on to lie in unvisited graves. Without them, our lives are more likely go badly:

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me [my italics] as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

Here’s what Fletcher has to say about Eliot’s “invention”:

“You and me” occurs rarely in literature and for good reason. It has a shorter and more elegant synonym: us….But “you and me”…does have a practical use in daily speech: it helps our brain bond to other people. Unlike “us,” which accepts that we’re already bonded, “you and me” stimulates when we’re not bonded yet, that feeling wraps our consciousness around a new coalition; in cases when we’re bonded already, it renews our sense of the union….That coming together isn’t an assumed fact of life, and it needs to be emphasized to make sure that the parties involved understand.

And what’s the larger significance of this? Fletcher sees Eliot’s novel as forwarding the idea of humanism as a sacred cause. When the German philosopher Feurbach tried to advance the notion that we should have a religious faith, not in God, but in people, he was roundly denounced. Christians considered him blasphemous while atheists thought him not atheist enough. But Eliot figured the vision could be conveyed through novels, and in fact I carry this vision away from Middlemarch. It may be one reason I like it so much.

Fletcher has one more example of “you and me.” During the Great Depression, Woody Guthrie objected to the song “God Bless America,” with its focus on God-bestowed blessings. So he wrote a counter song to get at his humanistic vision. As Fletcher explains, his song highlighted “every human being that travels here in plain view.” It is, of course, “This Land Is Your Land,” with its refrain, “This land was made for you and me.”

If you and I see ourselves as Dorotheas, quietly working on behalf of the human community, then we are living out Feurbach’s and Eliot’s vision. And we, of course, are beneficiaries of others doing the same, including when we pick up a novel to read. As Fletcher points out,

For such is the marvel of George Eliot’s invention that you can carry it into every novel that you read. All you need to do is pause when the novel is done—and think of all the nameless acts of love that helped create it.

Think of all the people who gave their hours to provide the novelist’s bread. Think of all the hands that built the schoolrooms where she learned. Think of all the strangers who labored in shadow to give her pen and ink and paper, strangers whome she’d never see.

Then think of her, wrestling against confusion and self-doubt and endless false starts to carry her narrative to its last shining word.

And all of it for readers whom she’d never see.

All of it for you and me.

I’ve always been deeply grateful, in my bones, for those who provide me with the literature I love. I have also seen it as my life’s work to share the gift of literature with students, and it doesn’t matter whether or not they remember me or the class, just as long as they were somehow touched. We’re all part of this vast human enterprise, with wealth and fame ultimately being far less important than what we give.

I’m still unsure about “you and me” being an invention. But that Eliot’s novels–Middlemarch and Silas Marner and Adam Bede and Mill on the Floss and Daniel Deronda–all convey the sense that there is a broader human community that we are part of and that we owe our lives to—now that I totally buy.