Spiritual Sunday

My colleague Ben Click, who teaches Mark Twain and American humor courses, is conducting a Lenten series on Flannery O’Connor for area Episcopal churches. I’ve long noticed the importance of grace in O’Connor’s work, but Ben, who is Catholic, has opened my eyes to just how much her Catholicism shapes her stories.

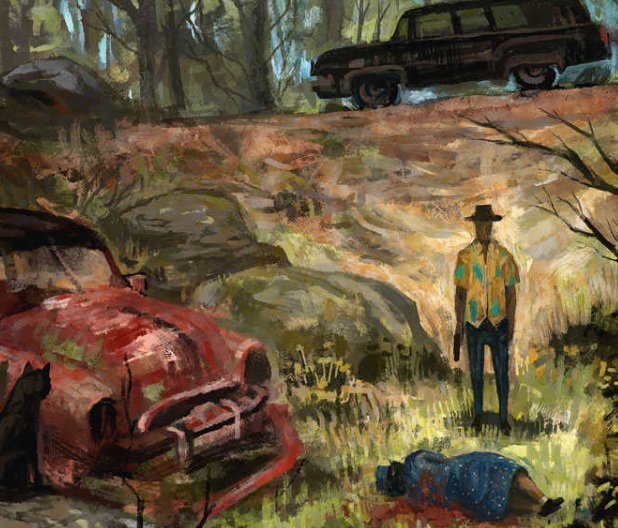

Ben challenged his first class with “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” one of the most shocking short stories ever penned. The class came to see it as a profound meditation on doubt and faith.

The story is about a field trip taken by a family, and we see the action mostly through the eyes of the grandmother, a self-righteous and self-absorbed woman who smugly spouts platitudes and is more interested in social propriety than right relationship. At one point in the story she triggers a set of mishaps that sends the car off the road, and the family is discovered by “The Misfit” and his murderous gang.

While the gang proceeds to execute the family, including the two children and the baby, the grandmother invokes prayer and Jesus in an attempt to awaken The Misfit’s conscience. Instead she finds herself gazing into a spiritual abyss. Describing life in prison, The Misfit essentially describes an absurd world of unexplained suffering. She contends that prayer would have saved him but he reports seeing only walls. Think of it as a Dostoyevskan depiction of existential hell:

“Pray, pray,” the grandmother began, “pray, pray . . .”

“I never was a bad boy that I remember of,” The Misfit said in an almost dreamy voice, “but somewheres along the line I done something wrong and got sent to the penitentiary. I was buried alive,” and he looked up and held her attention to him by a steady stare.

“That’s when you should have started to pray,” she said. “What did you do to get sent to the penitentiary that first time?”

“Turn to the right, it was a wall,” The Misfit said, looking up again at the cloudless sky. “Turn to the left, it was a wall. Look up it was a ceiling, look down it was a floor. I forget what I done, lady. I set there and set there, trying to remember what it was I done and I ain’t recalled it to this day. Oncet in a while, I would think it was coming to me, but it never come.”

The Misfit’s words remind me of George Herbert’s anguished cry to God in “Denial”:

The grandmother invokes Jesus, but more out of fear than in any meaningful way. (“[S]he found herself saying, “Jesus. Jesus,” meaning, Jesus will help you, but the way she was saying it, it sounded as if she might be cursing.”) This prompts The Misfit to describe the dread implications of a world without faith. If we don’t have a spiritual touchstone, ethical choices become meaningless and personal pleasure appears the only reliable guide:

“Jesus was the only One that ever raised the dead,” The Misfit continued, “and He shouldn’t have done it. He shown everything off balance. If He did what He said, then it’s nothing for you to do but throw away everything and follow Him, and if He didn’t, then it’s nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can by killing somebody or burning down his house or doing some other meanness to him. No pleasure but meanness,” he said and his voice had become almost a snarl.

With this stark declaration, uttered with absolute certainty, The Misfit pulls the grandmother into his dark universe so that she commits an act of Peter betrayal. He himself follows this up with a version of Thomas’ doubt:

“Maybe He didn’t raise the dead,” the old lady mumbled, not knowing what she was saying and feeling so dizzy that she sank down in the ditch with her legs twisted under her.

“I wasn’t there so I can’t say He didn’t,” The Misfit said. “I wisht I had of been there,” he said, hitting the ground with his fist. “It ain’t right I wasn’t there because if I had of been there I would of known. Listen lady,” he said in a high voice, “if I had of been there I would of known and I wouldn’t be like I am now.”

And then, improbably, grace intervenes. Seeing his intense misery, the grandmother is somehow able to reach beyond her own fear, self-absorption, and sin-filled existence to a place of genuine compassion. It costs her her life but, as my colleague notes, she dies in a state of grace.

His voice seemed about to crack and the grandmother’s head cleared for an instant. She saw the man’s face twisted close to her own as if he were going to cry and she murmured, “Why you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children!” She reached out and touched him on the shoulder. The Misfit sprang back as if a snake had bitten him and shot her three times through the chest. Then he put his gun down on the ground and took off his glasses and began to clean them.

Hiram and Bobby Lee returned from the woods and stood over the ditch, looking down at the grandmother who half sat and half lay in a puddle of blood with her legs crossed under her like a child’s and her face smiling up at the cloudless sky.

Note the child image and the smile. The grandmother early in the story would never have wanted to be seen in such an unladylike posture, but now the clouds have cleared. In the story’s most famous line, The Misfit bears witness that she has found what he longs for:

“She would of been a good woman,” The Misfit said, “if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

He, on the other hand, is condemned to a life of perpetual misery. Despite his earlier claim that one can find pleasure in meanness, he knows that he is condemned to a life of despair:

“Some fun!” Bobby Lee said.

“Shut up, Bobby Lee,” The Misfit said. “It’s no real pleasure in life.”

This is rough stuff, but that makes it all the more appropriate for Lent. Real faith isn’t easy.