Spiritual Sunday

I very much enjoy James Richardson’s casual conversation with God in “Evening Prayer.” I imagine the speaker kneeling in a mostly empty church as he launches into a reasonable exploration of religious rules and rituals. By the poem’s conclusion, however, the speaker’s prayer has moved from logic into a mystical understanding which delivers, in return, a prayer from God.

The speaker begins by matter-of-factly excusing both God and humans for religion. We can’t blame God for religious wars, religious rulings made in panic (which almost always end badly), and religious purism (whose intolerance leads to violence). Nor can God blame us for being afraid of Time, “the only thing not yours.” The speaker then acknowledges, however, that any equivalence will be false since humans bear more of the blame than God. After all, we have a habit of adapting our belief systems to “what we wanted to hear.” We are obsessed above all with the commandment, “Thou shalt believe in religion’s rules”:

How can we blame you for what we have made of you,

war, panic rulings, desperate purity?

Who can blame us? Lord know, we are afraid of time,

terrible, wonderful time, the only thing not yours.

Granted, we heard what we wanted to hear,

were sentenced, therefore, to our own strange systems

whose main belief was that we should believe.

In the second stanza, the speaker reinforces the idea that religious rules are human constructs since God operates without them. Moreover, since only humans make choices, God gave us “Everything,” leaving the choosing up to us. “Everything” includes the imagination, which imagines “what isn’t”–namely, that God has come up with rules for us to live by and that we are God’s special people. What we do with our imagining, the speaker says, is “an error you leave uncorrected”:

You, of course, are not religious, don’t need any rules

that can be disobeyed, have no special people,

and since a god, choosing (this the myths got right),

becomes human, avoided choices

in general, which is why there is Everything,

even imagination, which thinks it imagines

what isn’t, an error you leave uncorrected.

The final stanza humorously imagines that God released (to Nietzsche among others) the rumor that God is dead, thereby throwing us out of clear rules and back on faith. Uncertain, we can only “Pray into what you have made.”

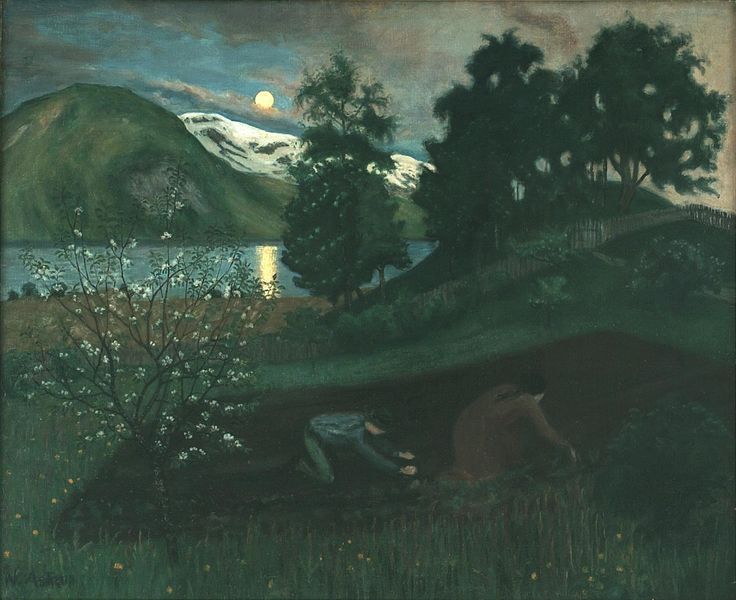

Once we leave behind the notion that God is a divine accountant tallying up who is orthodox and who is not, we are left with something greater. God is like a lake at night into which all are peacefully received—“the overhanging pine, the late-arriving stars, and all the news of men, weigh as they will.” Our pupils widen in wonder:

The rumor you were dead, you, I think,

suggested, letting us got with only Pray

into what you had made. By which you meant,

I know, nothing the divine accountants

could tote up on their abaci click, click,

but to widen like a pupil in the dark.

To be a lake, on which the overhanging pine,

the late-arriving stars, and all the news of men,

weigh as they will, are peacefully received,

to hear within the silence, not quite silence

your prayer to us, Live kindly, live.

In the not quite silence of this lake, our evening prayer is answered with a return prayer. What more foundational could God ask of us than that we live kindly and that we live?