Thursday

Secretary of Defense General James Mattis is proving to be one of the few bright spots in the Trump administration, fighting to save the Iran nuclear agreement against a hostile president. It was therefore heartening for me to hear that he is also a voracious reader.

According to Foreign Policy magazine, the general has accumulated “perhaps one of the largest personal libraries of an active-duty military officer ever known in the modern world.” Although most of the books Mattis mentions in FP’s interview have to do with politics and military history, he also lists a historical romance that I have read.

In response to a question about the relationship of personal development and dealing with violence, Mattis responds,

Well, personal development is a broader issue when you deal with violence. If you don’t have an understanding of a letter from a Birmingham jail, and how Sherman put the enemy on the horns of the dilemma, and how Scipio Africanus was able to triumph, if you can’t take those lessons of life and tie them together as a military commander, you’re going to have a hell of a difficult time, especially in a democracy where if you rise to high rank, you’re selected for tactical reasons, and operational, but then you have to deal with strategic reasons, and often you’re bringing war’s grim realities and trying to reconcile those with the political leaders you eventually deal with, their human aspirations, which are for a much better world than the primitive, atavistic one of the battlefield.

So you develop by broadening your understanding of human nature, of the ascent of man and everything else so that you can reconcile war’s realities, grim as they are, atavistic and primitive, with human aspirations, without becoming a narrow-minded person who at that point, you ought to give good military advice, but you can’t do so without trying to achieve a better peace, and so you need to have that broader reading as you grow and personally develop so you can actually do the job as a military officer, if you’re so fortunate that they keep you around long enough that you get promoted for a while.

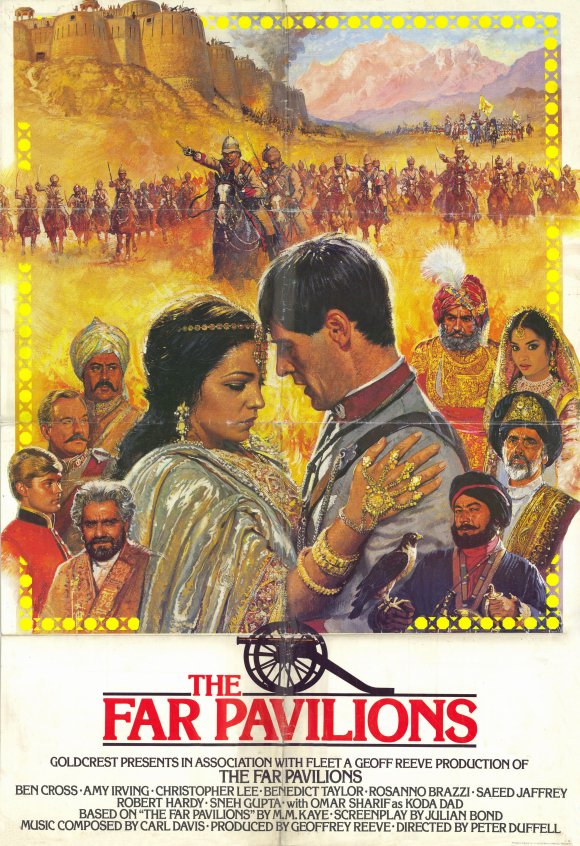

I guess on a tactical level there was a novel by M. M. Kaye called The Far Pavilions, and, of course, Guy Sajer’s The Forgotten Soldier. Nate Fick had One Bullet Away, and there’s some others on the tactical level.

Far Pavilions (1978) is a gripping Kim-type story set in the 19th century that culminates in a famous British defeat in the Second Afghan War. I became engrossed in it on my way to an MLA job interview in 1980 and still remember tiny details.

I understand why Mattis cites it. It is, after all, about a British blunder that cost the lives of 969 British and Indian soldiers after they were ambushed by Afghan rebels. It has tactical lessons in that regard, perhaps particularly poignant to Mattis since it is now Americans who are fighting and dying in Afghanistan.

But there’s another side to the novel that he may find relevant. Protagonist Ashton is born British but, because he loses his parents, he is raised Indian so that he has a foot in each world. Ashton goes on to join the Corps of Guides when he discovers his English parentage, and because he knows the language and the customs of the local populace, he can clearly see when his superiors are making stupid mistakes.

His special knowledge causes him great internal anguish. Should he blindly obey orders even when he knows they will lead to disaster? If he ignores his place and speaks up to his commanders, telling them the truth, will it even make any difference? As it turns out, he does warn the commanders about the trap, pays a price for doing so, and is ignored. A massacre results.

You can see where I’m going with this. General Mattis has a clarity that Donald Trump lacks, especially as the president promises to reduce North Korea to ashes. Trump has been similarly blind with regard to Iran, transgenders in the military, and other matters. To be sure, since Mattis is the Secretary of Defense and not a mere serviceman, his voice should command more respect. But Trump has been criticizing him him and also blindsided him on the transgender matter. The general must relate to Ashton in that respect.

The novel doesn’t have any clear answers—in fact, it suggests that there is nothing that Ashton can do to ward off the looming disaster–but at least it provides Mattis with a heroic narrative through which to process his own situation. The good news is that the story helps him see his options clearly. The bad news is that the author stresses the heroism of laying down your life for a battle you know will be lost. The book has a happy ending only because the hero is knocked out in the battle (thus, he doesn’t survive by fleeing) and is saved by the heroine.

If Mattis sees it as his duty to go along as the president marches us into nuclear confrontation with North Korea, he won’t be the only victim. He owes it to the country to speak his mind and to resign if he sees the president as a clear and present danger to us and to the world.