I’ve just finished teaching John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath and am still marveling at the powerful civics lessons that it provides us. I asked the students for solutions—what should be done to address the plight of the Okies?—and the ensuing discussion reached into virtually every character and every situation in the book.

We couldn’t help but touch on many of the political debates set off by the 2008 crash. The hard edges that were revealed by America’s most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression has made Steinbeck’s masterpiece relevant again.

In Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck shows us evicted farmers, sales clerks, car salesmen, bankers, large landowners, small landowners, cops, vigilantes, border patrol inspectors–the list goes on as he lays out a country in crisis. Who succeeds and who fails almost seems a matter of chance. There are the Oklahoma farmers who stay and the ones who migrate, those lucky few who find jobs working for the people in power and those thousands who must take to the roads. He shows a wide range of individual responses to hardship—those who give up, those who run away, those who lash out, those who keep on plodding.

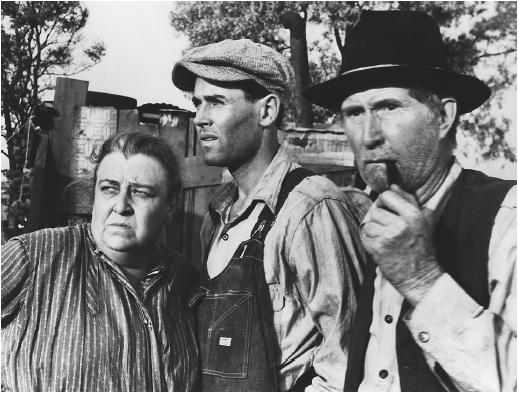

Moving between close-up and long shot in alternating chapters, Steinbeck gives us both the Joad family and the mass migration. If he only showed us the Joads, he would leave us believing that individual solutions are possible. On the other hand, if he showed us only the collective throngs, he would risk dehumanizing the crisis. The alternating format reminds us that, even should the Joads pull through, there are many more families that also need help.

I can’t do justice to every issue we discussed but here’s a sampling. The students wondered why Mae, who works in a diner, is so hard-hearted about the price of a loaf of bread, insisting that she be paid 15 cents for it. But as they explored her situation, they understood why she has become hard: if she undersold bread to every family that came through, the store would go out of business and she herself would be out of a job. They then became impressed by how she softens, pretending that two pieces of five-cent candy cost a penny, thereby allowing the father to keep his dignity rather than seeing himself as an object of charity. And by how, when Mae herself becomes such an object—a truck driver rewards her with a generous tip—she can’t acknowledge it. Steinbeck’s grasp of the psychology of poverty is impressive.

And now look at Steinbeck describing the psychology of the owners who are evicting the Okies, a psychology we can see at play among members of our own 1% as income disparities widen:

Some of the owner men were kind because they hated what they had to do, and some of them were angry because they hated to be cruel, and some of them were cold because they had long ago found that one could not be an owner unless one were cold. And all of them were caught in something larger than themselves. Some of them hated the mathematics that drove them, and some were afraid, and some worshiped the mathematics because it provided a refuge from thought and from feeling.

The students were particularly drawn to Chapter 25, which is the one where we see food being destroyed lest it drive down prices. The last paragraph gives the novel its title:

The people come with nets to fish for potatoes in the river, and the guards hold them back; they come in rattling cars to get the dumped oranges, but the kerosene is sprayed. And they stand still and watch the potatoes float by, listen to the screaming pigs being killed in a ditch and covered with quicklime, watch the mountains of oranges slop down to a putrefying ooze; and in the eyes of the people there is a failure; and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.

Again, I challenged the students to work out the economics of the situation and come up with answers. Interestingly enough, in the end most of the students were calling for government solutions—for instance, government-run (which is to say, taxpayer-financed) food banks that paid farmers a fair price and distributed produce to the unemployed. In the face of Steinbeck’s images of hardship and misery, no one advocated an Ayn Randian libertarianism. Most found themselves rooting for Steinbeck’s collectivist vision, even as they fully acknowledged (as he does) America’s strong individualist ethos.

In this age when politicians like Paul Ryan and Rand Paul take shots at the entitlement programs that grew out of the Great Depression, Grapes of Wrath is a good reminder of what the world looks like without social safety nets: children with rickets and pellagra, people going hungry because they can’t find employment, families broken apart by poverty. Grapes of Wrath should be required reading for everyone who has become complacent.